Rhythm, Meter, and Scansion Made Easy

advertisement

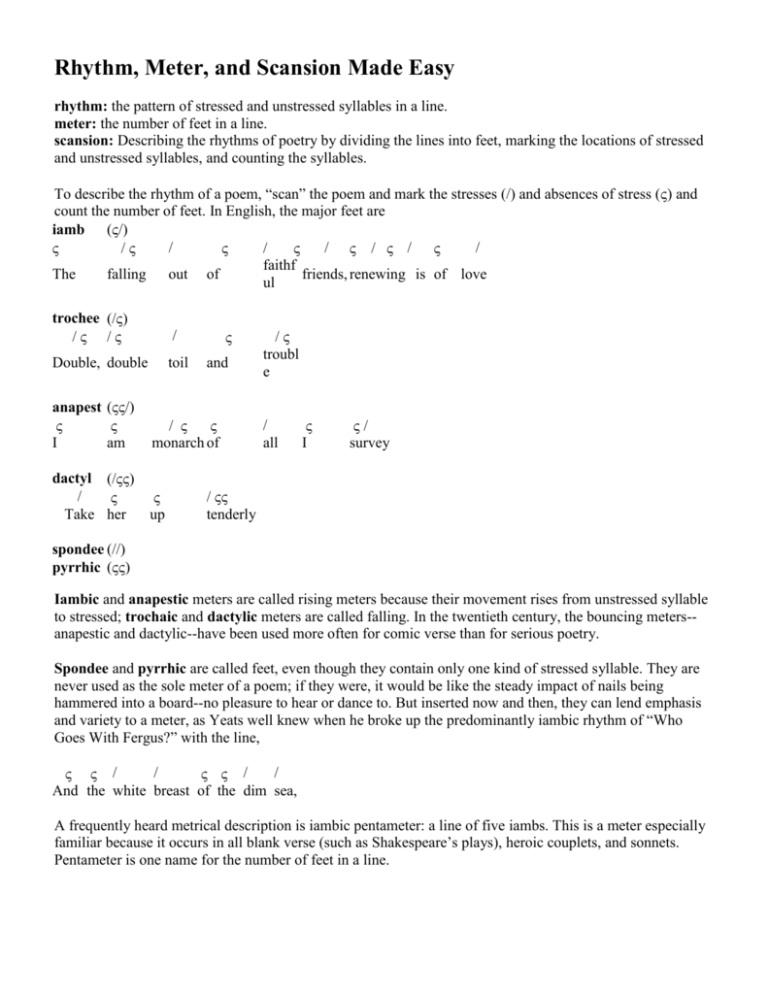

Rhythm, Meter, and Scansion Made Easy rhythm: the pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables in a line. meter: the number of feet in a line. scansion: Describing the rhythms of poetry by dividing the lines into feet, marking the locations of stressed and unstressed syllables, and counting the syllables. To describe the rhythm of a poem, “scan” the poem and mark the stresses (/) and absences of stress () and count the number of feet. In English, the major feet are iamb (/) / / / / / / / faithf The falling out of friends, renewing is of love ul trochee (/) / / / Double, double toil and anapest (/) I am / monarch of dactyl (/) / Take her up / troubl e / all I / survey / tenderly spondee (//) pyrrhic () Iambic and anapestic meters are called rising meters because their movement rises from unstressed syllable to stressed; trochaic and dactylic meters are called falling. In the twentieth century, the bouncing meters-anapestic and dactylic--have been used more often for comic verse than for serious poetry. Spondee and pyrrhic are called feet, even though they contain only one kind of stressed syllable. They are never used as the sole meter of a poem; if they were, it would be like the steady impact of nails being hammered into a board--no pleasure to hear or dance to. But inserted now and then, they can lend emphasis and variety to a meter, as Yeats well knew when he broke up the predominantly iambic rhythm of “Who Goes With Fergus?” with the line, / / / / And the white breast of the dim sea, A frequently heard metrical description is iambic pentameter: a line of five iambs. This is a meter especially familiar because it occurs in all blank verse (such as Shakespeare’s plays), heroic couplets, and sonnets. Pentameter is one name for the number of feet in a line. The commonly used names for line lengths are: monometer one foot pentameter five feet two feet dimeter hexameter six feet three feet trimeter heptameter seven feet eight feet tetrameter four feet octameter The scansion of this quatrain from Shakespeare’s Sonnet 73 shows the following accents and divisions into feet (note the following words were split: behold, yellow, upon, against, ruin'd): ^ / ^ / ^ / ^ / ^ / That time | of year | thou mayst | in me | be hold | ^ / ^ / ^ / ^ / ^ / When yel | low leaves, | or none, | or few, | do hang | ^ / ^ / ^ / ^ / ^ / Up on | those boughs | which shake | a gainst | the cold, | ^ / ^ / ^ / ^ / ^ / Bare ru | in'd choirs | where late | the sweet birds sang | The rhythm of this quatrain is made up of one unaccented syllable followed by an accented syllable, called an iambic foot. There are five feet per line, making the meter of the line pentameter. So, the rhythm and meter are iambic pentameter. Scan these poem excerpts: The morns are meeker than they were, The nuts are getting brown; The berry’s cheek is plumper, The rose is out of town. --Emily Dickinson Bats have webby wings that fold up; Bats from ceilings hang down rolled up; Bats when flying undismayed are; Bats are careful; bats use radar; --Frank Jacobs, “The Bat” You know that it would be untrue, You know that I would be a liar, If I was to say to you Girl, we couldn’t get much higher. Come on, baby, light my fire. Try to set the night on fire. --Jim Morrison, “Light My Fire” Poetic Meter and Scansion Trochee trips from long to short; From long to long in solemn sort Slow spondee stalks; strong foot! yet ill able Ever to come up with dactyl trisyllable. Iambics march from short to long; -With a leap and a bound the swift Anapests throng; One syllable long, with one short at each side, Amphibrachys hastes with a stately stride:-First and last being long, middle short, Amphimacer Strikes his thundering hoofs like a proud high-bred Racer. -- From "Metrical Feet" by Samuel Taylor Coleridge Many traditional and some modern poems are metrical -- that is, every line is based on some particular rhythmic pattern, or meter. When you go shopping for clothes, you often need to know two things about the size of a garment in order to make sure it will fit you: for instance, "Waist 34 Leg 36," or "Collar 15 1/2 Sleeve 33." A poem's meter is named much the same way -- using two variables. The first part of the name is the foot: it indicates the pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables which will be repeated within a single line. The second part of the name indicates how many of those feet there are in a line. 1. Metrical Feet in English Poetry Stressed and unstressed syllables refer to the difference in emphasis that a syllable receives. Thus in the line The quick fox jumps over the lazy dog the syllables stressed by a native speaker of English are in bold type. Notice that not all of these stresses are equally heavy; the heaviest syllable in the sentence is probably "fox" and the lightest stressed syllable is the "o" of "over". In determining the basic meter of a poem, however, those differences do not matter --a syllable is either stressed or unstressed. The following is a table of the most commonly used metrical feet in English. Stressed syllable: 2 syllables 3 syllables last iamb: inspire anapest: anymore first trochee: travel dactyl: dinosaur both first and last spondee: spice rack amphimacer: amazon neither pyrric: and a amphibrachys: amoeba Notes Very few English words have anapestic stress. In poetry, this foot is often made up of a prepositional phrase or other word group: "See a man in a boat on the sea with a fish ." The dactyl gets its name from the Greek word for "finger," as in pterodactyl (wing-finger). The ancient Greek poets, who came up with these foot names, compared the "strong-weak-weak" pattern to the structure of the human finger, in which the first bone is the longest. Other spondees include ingrown, ice pick, and android. Notice that the two syllables tend to be separated by a consonant cluster which forces them to each stand alone instead of one swallowing up the other. There is also such a thing as a monosyllabic foot, which is usually found replaced a normal 2or 3-syllable foot for variety or emphasis. However, Gwendolyn Brooks' "We Real Cool" can be reasonably described as a poem written entirely in monosyllabic feet. Excerpt from Soliloquy Of The Spanish Cloister by Robert Browning III. Whew! We'll have our platter burnished, Laid with care on our own shelf! With a fire-new spoon we're furnished, And a goblet for ourself, Rinsed like something sacrificial Ere 'tis fit to touch our chaps--Marked with L. for our initial! (He-he! There his lily snaps!) IV. _Saint_, forsooth! While brown Dolores Squats outside the Convent bank With Sanchicha, telling stories, Steeping tresses in the tank, Blue-black, lustrous, thick like horsehairs, ---Can't I see his dead eye glow, Bright as 'twere a Barbary corsair's? (That is, if he'd let it show!) Alfred Lord Tennyson (1809-1892) The Eagle 1He clasps the crag with crooked hands; 2Close to the sun in lonely lands, 3Ring'd with the azure world, he stands. 4The wrinkled sea beneath him crawls; 5He watches from his mountain walls, 6And like a thunderbolt he falls. Wilfred Owen (1893-1918) Dulce et Decorum Est 1Bent double, like old beggars under sacks, 2Knock-kneed, coughing like hags, we cursed through sludge, 3Till on the haunting flares we turned our backs, 4And towards our distant rest began to trudge. 5Men marched asleep. Many had lost their boots, 6But limped on, blood-shod. All went lame, all blind; 7Drunk with fatigue; deaf even to the hoots 8Of gas-shells dropping softly behind. 9Gas! GAS! Quick, boys!--An ecstasy of fumbling 10Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time, 11But someone still was yelling out and stumbling 12And flound'ring like a man in fire or lime.-13Dim through the misty panes and thick green light, 14As under a green sea, I saw him drowning. 15In all my dreams before my helpless sight 16He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning. 17If in some smothering dreams, you too could pace 18Behind the wagon that we flung him in, 19And watch the white eyes writhing in his face, 20His hanging face, like a devil's sick of sin, 21If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood 22Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs 23Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud 24Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues,-25My friend, you would not tell with such high zest 26To children ardent for some desperate glory, 27The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est 28Pro patria mori. Dorothy Parker (1893-1967) Resumé 1Razors pain you; 2Rivers are damp; 3Acids stain you; 4And drugs cause cramp. 5Guns aren't lawful; 6Nooses give; 7Gas smells awful; 8You might as well live. Emily Dickinson (1830-1886) The Chariot 1Because I could not stop for Death, 2He kindly stopped for me; 3The carriage held but just ourselves 4And Immortality. 5We slowly drove, he knew no haste, 6And I had put away 7My labor, and my leisure too, 8For his civility. 9We passed the school where children played, 10Their lessons scarcely done; 11We passed the fields of gazing grain, 12We passed the setting sun. 13We paused before a house that seemed 14A swelling of the ground; 15The roof was scarcely visible. 16The cornice but a mound. 17Since then 'tis centuries; but each 18Feels shorter than the day 19I first surmised the horses' heads 20Were toward eternity. Edgar Allan Poe (1809-1849) Excerpt from The Raven 1 Once upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered, weak and weary, 2Over many a quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore-3 While I nodded, nearly napping, suddenly there came a tapping, 4As of some one gently rapping, rapping at my chamber door. 5"'Tis some visiter," I muttered, "tapping at my chamber door-6 Only this and nothing more." 7 Ah, distinctly I remember it was in the bleak December; 8And each separate dying ember wrought its ghost upon the floor. 9 Eagerly I wished the morrow;--vainly I had sought to borrow 10 From my books surcease of sorrow--sorrow for the lost Lenore-11For the rare and radiant maiden whom the angels name Lenore-12 Nameless here for evermore. 13 And the silken, sad, uncertain rustling of each purple curtain 14Thrilled me--filled me with fantastic terrors never felt before; 15 So that now, to still the beating of my heart, I stood repeating 16 "'Tis some visiter entreating entrance at my chamber door-17Some late visiter entreating entrance at my chamber door;-18 This it is and nothing more." Upon Julia's Clothes Robert Herrick (1591-1674) 1Whenas in silks my Julia goes, 2Then, then (methinks) how sweetly flows 3That liquefaction of her clothes. 4Next, when I cast mine eyes, and see 5That brave vibration each way free, 6O how that glittering taketh me! Alfred Lord Tennyson (1809-1892) Excerpt from The Charge of the Light Brigade 1Half a league, half a league, 2 Half a league onward, 3All in the valley of Death 4 Rode the six hundred. 5`Forward, the Light Brigade! 6Charge for the guns!' he said: 7Into the valley of Death 8 Rode the six hundred. II 9`Forward, the Light Brigade!' 10Was there a man dismay'd? 11Not tho' the soldier knew 12 Some one had blunder'd: 13Their's not to make reply, 14Their's not to reason why, 15Their's but to do and die: 16Into the valley of Death 17 Rode the six hundred. III 18Cannon to right of them, 19Cannon to left of them, 20Cannon in front of them 21 Volley'd and thunder'd; 22Storm'd at with shot and shell, 23Boldly they rode and well, 24Into the jaws of Death, 25Into the mouth of Hell 26 Rode the six hundred. Excerpt from A Visit From St. Nicholas By Clement C. Moore 'Twas the night before Christmas, when all through the house Not a creature was stirring, not even a mouse; The stockings were hung by the chimney with care, In hopes that St. Nicholas soon would be there; The children were nestled all snug in their beds, While visions of sugar-plums danced in their heads; And mamma in her 'kerchief, and I in my cap, Had just settled down for a long winter's nap, When out on the lawn there arose such a clatter, I sprang from the bed to see what was the matter. Away to the window I flew like a flash, Tore open the shutters and threw up the sash. The moon on the breast of the new-fallen snow Gave the lustre of mid-day to objects below, When, what to my wondering eyes should appear, But a miniature sleigh, and eight tiny reindeer, With a little old driver, so lively and quick, I knew in a moment it must be St. Nick. More rapid than eagles his coursers they came, And he whistled, and shouted, and called them by name; Tell all the Truth but tell it slant Emily Dickinson Tell all the Truth but tell it slant--Success in Cirrcuit lies Too bright for our infirm Delight The Truth's superb surprise As Lightening to the Children eased With explanation kind The Truth must dazzle gradually Or every man be blind--- Simple Scansion Metrical Feet: Stressed Syllable 2 Syllables 2 Syllables last iamb: inspire anapest: anymore first trochee: travel dactyl: dinosaur both first and last spondee: spice rack amphimacer: amazon neither pyrric: and a amphibrachys: amoeba Meter: monometer (exceedingly rare) dimeter trimeter (rare) tetrameter pentameter hexameter (also known as alexandrine) heptameter octameter nonamater decameter Common meter names: iambic pentameter – natural rhythm of spoken English Ex: from Wilfred Owen’s “Dulce et Decorum Est” Till on the haunting flares we turned our backs And towards our distant rest3 began to trudge. iambic tetrameter Ex: from Tennyson’s “The Eagle” The wrinkled sea beneath him crawls; He watches from his mountain walls, And like a thunderbolt he falls. iambic heptameter when written as two lines, one of four feet and the next of three, this is known as “ballad meter” from its common use in folk and popular song; it is also used in serious poetry. Ex: Dickinson’s :Tell All The Truth But Tell It Slant” Tell all the Truth but tell it slant--Success in Cirrcuit lies Too bright for our infirm Delight The Truth's superb surprise As Lightening to the Children eased With explanation kind The Truth must dazzle gradually Or every man be blind--- trochaic dimeter Ex: from Parker’s “Resume” Razors pain you trochaic tetrameter Ex: from Browning’s “Soliloquy of the Spanish Cloister” Oh, that rose has prior claims-Needs its leaden vase filled brimming? trochaic octometer Ex: from Poe’s “The Raven” Once upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered, weak and weary, anapestic dimeter Ex: Dr. Seuss’s The Cat in the Hat anapestic tetrameter – triple meters associated with light or comic tone Ex: Moore’s “A Visit From St. Nicholas” ‘Twas the night before Christmas and all through the house Not a creature was stirring, not even a mouse. amphimacer dimeter Ex: Tennyson’s “The Charge of the Light Brigade” Half a league, half a league, sprung rhythm (Hopkins) – inserting a number of unstressed syllables in between the stressed syllables. Ex: “God’s Grandeur” The world is charged with the grandeur of God. It will flame out, like shining from shook foil, It gathers to a greatness like the ooze of oil Crushed. Why do men then now not reck His rod? Generations have trod, have trod, have trod; 5 And all is seared with trade; bleared, smeared with toil; And bears man’s smudge, and shares man’s smell; the soil Is bare now, nor can foot feel being shod. And for all this, nature is never spent; There lives the dearest freshness deep down things; 10 And though the last lights from the black west went, Oh, morning at the brown brink eastwards springs— Because the Holy Ghost over the bent World broods with warm breast, and with, ah, bright wings 2. Meter The second half of the meter name is just a number -- the number of feet in a line. 1. monometer (if anyone finds a poem like this, please let me know) 2. dimeter 3. trimeter 4. tetrameter 5. pentameter 6. hexameter 7. heptamater 8. octameter 9. nonameter 10. decameter and so on, although for obvious reasons anything longer than heptameter is fairly rare. Together, the two elements become a meter name. Some common meters, with poetic examples: iambic pentameter -- This is the king of English meters, established firmly at the top of the chain by the Elizabethan poets because it sounds like the natural rhythm of spoken English. Most sonnets are in this meter, including those of Shakespeare; one modern non-sonnet examples is Wilfred Owen, "Dulce Et Decorum Est". iambic tetrameter -- Robert Herrick, "Upon Julia's Clothes"; Tennyson, "The Eagle". iambic heptameter -- when written as two lines, one of four feet and the next of three, this is known as "ballad meter" from its common use in folk and popular song, but also used in serious poetry -- Emily Dickinson uses this meter extensively ("Tell All The Truth But Tell It Slant", among others). trochaic dimeter -- Dorothy Parker, "Resume" trochaic tetrameter -- Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, The Song of Hiawatha; Robert Browning, "Soliloquy of the Spanish Cloister" trochaic octameter -- Edgar Allen Poe, "The Raven" anapestic dimeter -- Dr. Seuss, "The Cat in the Hat" anapestic tetrameter -- Clement Moore, "A Visit From St. Nicholas"; Dr. Seuss, "How the Grinch Stole Christmas." Notice that triple meters tend to be associated with a light or comic tone. However, this can be used to create an ironic effect, as in W.H. Auden, "The Unknown Citizen". amphimacer dimeter -- The energy of the triple meter can also be used for dramatic effect, as in Alfred, Lord Tennyson, "The Charge of the Light Brigade". Feet, Meter, and Scansion We describe a line of poetry with a two-word naming system, kind of like we use for cars and other objects. Ford Mustang make model corn bread iambic pentameter what it’s what it type of number of made from is feet feet What is being described by this two-word name is the pattern of syllables in the line of poetry. The first word tells us the type of foot, and the second word tells us the number of that kind of foot, or the meter. The scansion of a poem, its feet and meter, are what give the poem rhythm. syllable (n): smallest single sound unit of a word. There are two types: stressed (or emphasized), and unstressed. Words that have more than one syllable (multi-syllabic words) will have one primary, or most heavily, stressed syllable. For example, the word “elephant” has three syllables; the first is the most-heavily stressed, the second is unstressed, and third is stressed a little bit. A multi-syllabic word may have one or more secondary, or less emphasized, stressed syllables. For example, the word “elevator” has four syllables; the first syllable is the primary stressed syllable, and the third syllable is a secondary stressed syllable (stressed, but not as heavily as the first syllable). Syllables two and four are unstressed. We can show which syllable is stressed in a word by writing a short diagonal mark over it ( / ). We can indicate an unstressed syllable by writing a small scoop mark over it ( U ). The syllable pattern for the word “elephant” would look like this: / U / foot (n): a group of stressed and unstressed syllables in a line of poetry Different patterns (or feet) have different names. Here are a few of the patterns and their names: · Iamb – unstressed stressed ( U / ) (adj: iambic) · Trochee – stressed unstressed ( / U ) (adj: trochaic) · Amphibrach – unstressed stressed unstressed ( U / U ) (adj: amphibrachic) · Anapest – unstressed unstressed stressed( U U / ) (adj: anapestic) · Dactyl – stressed unstressed unstressed ( / U U ) (adj: dactylic) · Spondee – stressed stressed ( / / ) (adj: spondaic) · Pyrrhus – unstressed unstressed ( U U ) (adj: pyrrhic) · Amphimacer – stressed unstressed stressed ( / U / ) (adj: cretic) In addition to knowing the pattern of the syllables (the kind of feet) that are in a line of a poem, we also want to know how many times that pattern repeats (how many feet there are). A line of one foot is monometer Two feet is dimeter Three feet is trimeter Four feet is tetrameter Five feet is pentameter Six feet is hexameter Seven feet is heptameter Eight feet is octameter Nine feet is nonameter Ten feet is decameter If there is no clear repetition of a foot, the line is named for the number of syllables it contains; an eight syllable line is octosyllabic, a ten syllable line is decasyllabic, etc. meter (n): the number of feet in a line of poetry scansion [or scan](v): finding the syllable patterns (feet and meter) in a poem or in a line of poetry (n): the syllable patterns in a poem or a line of poetry There are many different types of feet in poetry. One of the most common is the iamb. iamb (n) [adj – iambic]: a two-syllable foot made up of one unstressed syllable and one stressed syllable When, in disgrace with Fortune and men’s eyes, I all alone beweep my outcast state… [Shakespeare, Sonnet 29] As can be seen in this example, sonnets are usually written in iambic pentameter; the prefix “penta” tells us there are five iambic feet, or five groups of unstressed-stressed syllables. mono- : one tetra- : four hepta- : seven di- : two penta- : five octa- : eight tri- : three hexa- : six nona- : nine deca- : ten The opposite of the iamb is the trochee. trochee (n) [adj – trochaic]: a two-syllable foot made up of one stressed syllable and one unstressed syllable Tiger! Tiger! burning bright In the forests of the night… [Blake, “The Tiger”] This poem is described as being in trochaic trimeter. As you can see in this example, not all lines of poetry have an exact number of feet. Therefore, we describe a line of poetry or a poem by saying what most, if not all, of the feet are, and how many feet there are in most, if not all, of the lines. Feet can also have of three syllables; two of these, the amphibrach and the anapest, are seen in most limericks. The first, second, and fifth lines of a limerick are usually made up of three amphibrachic feet, while the third and fourth lines usually consist of two anapestic or amphibrachic feet. amphibrach (n) [adj – amphibrachic]: a three-syllable foot with an unstressed-stressed-unstressed pattern anapest (n) [adj – anapestic]: a three-syllable foot with an unstressed-unstressed-stressed pattern There was a young belle from old Natchez Whose garments were nothing but patches; When comment arose On the state of her clothes She replied, When Ah itchez, Ah scratches. (“Requiem” by Ogden Nash) Site prepared by Mr. S. Tetreault, Holmdel School District