Patient Safety Tips - Austin Community College

advertisement

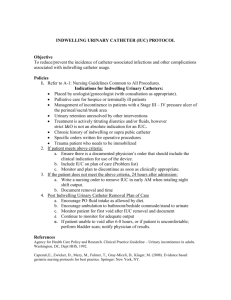

Patient Safety Tips Aligned with the Hospital Engagement Network (HEN) Initiative ASHRM is providing important patient safety tips and information throughout National Patient Safety Awareness Week that are in alignment with the Hospital Engagement Network (HEN) initiative that is part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Partnership for Patients. The goal of this initiative is to assist hospitals in adopting practices that have the potential to reduce inpatient harm by 40 percent and readmission by 20 percent. ASHRM will continue to be a resource to help improve patient safety in these areas: 1. Adverse drug events 2. Catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTI) 3. Central line-associated blood stream infections (CLABSI) 4. Injuries from falls and immobility 5. Obstetrical adverse events 6. Pressure ulcers 7. Surgical site infections 8. Venous thromboembolism (VTE) 9. Ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) 10. Preventable readmissions 1. Adverse Drug Events Most medications are beneficial, or at least cause no harm. Occasionally, drugs can injure patients. Some of these "adverse drug events" are unavoidable, such as an acute reaction. But errors in any of the following processes, or a combination of the processes, can cause patient harm: Procuring Prescribing Dispensing Administering Failing to monitor the effects of the medication given Many of these errors are not caused by individual carelessness, but by faulty processes that lead to human errors or fail to prevent the mistakes from occurring in the first place. Tips to preventing adverse drug events Patient education - One of the most effective ways to reduce medications errors is to move toward a model of healthcare where there is more of a partnership between patients and healthcare providers. Patients (and their families, when necessary) should understand more about the medications they are taking, and take active responsibility for managing their use. Providers should explain the medication's risks and possible side effects, and tell patients what to do if they experience a side effect. They also need to listen to their patient's concerns and provide effective alternative medications, when appropriate. Technology - Making greater use of technology, particularly with respect to prescribing and dispensing medications, is another important step toward reducing the number of medication errors. Health information technology makes it easier for a provider to research which drug would be best for a particular patient. Physician order entry and electronic prescriptions eliminate many errors caused by poor handwriting. Healthcare workers may also use this technology to check the patient's medical history to prevent drug allergies, interactions with other drugs and assure proper dosage. Improving labeling and packaging of medications will help to differentiate between "look-alike, sound-alike" medications. Medication reconciliation processes, which compare the patient's current list of medications against the physician's admission, transfer and/or discharge orders, also help to reduce medication errors. Source: Institute for Safe Medication Practices: www.ismp.org More tips for preventing adverse drug events are detailed in ASHRM Pearls for Medication Safety, available at the ASHRM online store. Click Here to order the booklet. 2. Catheter-associated Urinary Tract Infections (CAUTI) The urinary tract is the most common site of healthcare-associated infection, accounting for more than 30 percent of infections reported by hospitals, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Complications associated with CAUTI cause patient discomfort, prolonged hospital stay and increased patient mortality. Virtually all healthcare-associated urinary tract infections (UTIs) are caused by indwelling urinary catheters. Tips for preventing CAUTI The first and most important step nurses and other caregivers can take to prevent CAUTI is to wash their hands before inserting and managing indwelling urinary catheters. Other tips include: Develop organizational guidelines for urinary catheters - Each healthcare facility should have written guidelines on the use, insertion and maintenance of urinary catheters. These guidelines should specify when catheters are necessary, and restrict their use to patients with appropriate indications. Guidelines must delineate who is qualified and trained to insert urinary catheters, and include a system for documentation of insertion and removal of urinary catheters. Guidelines also should specify how catheter duration is monitored, and how data are collected to determine rates of symptomatic CAUTI. Some hospitals have found it helpful to develop daily checklists to monitor the duration of and need for a catheter. Follow proper insertion and management techniques - Urinary catheters should be inserted aseptically using barrier precautions such as sterile gloves, drapes, sponges, antiseptic solution and single-use packets of sterile lubricant. Use a catheter as small and as soft as possible to minimize urethral trauma, while still permitting proper drainage. Reduce unnecessary catheter use – Consider other methods for urinary management, such as condom catheters or in-and-out catheterization, before inserting indwelling catheters. In males requiring a urine collection device, the condom catheter is an alternative to the indwelling catheter. Not only are condom catheters more comfortable, but their use is associated with lower rates of bacteria and symptomatic UTI in male patients. Remove urinary catheters promptly – An organization-wide program should identify catheters that are no longer necessary and ensure their prompt removal. Nurses and other healthcare providers should review the necessity of continuing each urinary catheter daily. They can implement cues to evaluate catheter necessity, such as standardized reminders in the patient record or daily unit catheter rounds. Sources: Medscape Today: www.medscape.com/viewarticle/587464_4 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: www.cdc.gov/nhsn/pdfs/pscManual/7pscCAUTIcurrent.pdf 3. Central Line-associated Blood Stream Infections (CLABSI) A central line is a tube that is placed into a large vein in the patient's neck, chest, arm or groin and used to draw blood or give fluids and medications. It may be left in place for several weeks. A bloodstream infection can occur when bacteria or other germs travel down this tube and enter the blood. Patients who develop a central-line associated bloodstream infection may develop a fever and the skin around the catheter may become sore and red. Tips for preventing CLABSI Healthcare providers should choose a vein where the catheter can be safely inserted and where the risk for infection is small. Providers need to wash their hands and clean the patient's skin with an antiseptic cleaner before inserting the central line. Providers also should wear a mask, cap, sterile gown and sterile gloves when putting in the line to keep it sterile. Also, the patient should be covered with a sterile sheet. Before using the line to draw blood or give medications, providers need to clean their hands, wear gloves and clean the central line opening with an antiseptic solution. Evaluate every day if patients still need the central line and remove it as soon as it is not needed. Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: www.cdc.gov/nhsn/pdfs/pscmanual/4psc_clabscurrent.pdf 4. Patient Falls Falls occur in all types of healthcare institutions and to all patient populations. However, patients most at risk include the elderly and frail, and those on medication regimens such as anticoagulant therapy. Patient falls lead to obvious physical consequences such as fractures and soft tissue or head injuries. However, patients who fall also suffer emotional consequences such as fear, anxiety and depression. Some falls are difficult to prevent, such as those caused by intrinsic risk factors including: Patient history of falls Reduced vision Unsteady gait Mental status Acute illnesses Falls caused by extrinsic risk factors are easier to prevent. Common extrinsic risk factors include: Medications that affect the central nervous system Bathtubs and toilets without grab bars Conditions of ground surfaces Poor lighting Condition of footwear Improper use of bedside rails and other mechanical restraining devices Tips for preventing patient falls Once a patient is determined to be at risk of falling, it becomes a priority to communicate this risk to all staff, the patient, and the patient's family. This task can be accomplished through the medical record, handoff communications, signage (door, wall, wristband), and other methods that continue to alert staff to the patient's risk. Interventions to prevent injury in the acute and long-term care settings include limiting restraint use, lowering bedrails, frequent staff rounding, using hip protectors in long-term care, and prescribing calcium with vitamin D, and possibly bisphosphonates (a class of drugs that prevent the loss of bone mass, used to treat osteoporosis and similar diseases) to patients in long-term care. Source: Joint Commission Resources: www.jcrinc.com/Preventing-Patient-Falls 5. Obstetrical Adverse Events: Perinatal Death or Loss of Function A healthy and safe birth for the mother and infant is the goal for all labor and delivery units. A celebratory event turns to tragedy when a birth results in the newborn's death or permanent injury. The absence of early and regular prenatal care is a leading contributor to the risk of infant death. Other risk factors include maternal age, history of diabetes and substance abuse. Complications that can occur during labor include failing to recognize a non-reassuring fetal status on the fetal monitor. Complications during birth include placental abruption, ruptured uterus and breech presentation. Although some infant deaths cannot be prevented, breakdowns in care can contribute to birth complications. Some root causes of birth complications identified by The Joint Commission include: Communication issues Staff competency Orientation and training process Inadequate fetal monitoring Unavailable monitoring equipment or drugs Physician unavailable or delayed Tips to prevent perinatal death or loss of function The Joint Commission's "Sentinel Event Alert, Issue 30: Preventing infant death and injury during delivery" outlines strategies to reduce risk of perinatal death, including: Revise orientation and training process Provide physician education and counseling Revise communication protocols Reinforce chain-of-communication policy Revise competency assessment Standardize equipment and drug availability Source: The Joint Commission: www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/18/SEA_30.PDF Risk management techniques to help prevent obstetrical adverse events are explained in ASHRM Pearls for Obstetrics, available at the ASHRM online store. Click Here to order the booklet. 6. Pressure Ulcers Pressure ulcers, also called bed sores, are injuries to the skin and underlying tissues that result from prolonged pressure on the skin. Bedsores most often develop on the skin that covers bony areas of the body, such as the heel, ankles, hips or buttocks. People most at risk of pressure ulcers are those with a medical condition that limits their ability to change positions, requires them to use a wheelchair or confines them to a bed for prolonged periods. Left untreated, pressure ulcers can develop into: Sepsis – bacteria enters the bloodstream through the broken skin Cellulitis – an acute infection of skin's connective tissue causing pain, redness and swelling Bone and joint infections – infections that occur when the infection from a pressure sore burrows deep into joints and bones Cancer – a type of squamous cell carcinoma can develop in chronic, nonhealing wounds Tips for preventing pressure ulcers Bedsores can develop quickly and are often difficult to treat. Several care strategies can help prevent some bedsores and promote healing. Repositioning – People in a wheelchair should change positions on their own, as much as possible, every 15 minutes and should have assistance with changes in position every hour. Pressure-release wheelchairs, which tilt to redistribute pressure, provide some assistance in repositioning and pressure relief. People confined to bed should be repositioned every two hours. Support surfaces – Special cushions, foam mattress pads, air-filled mattresses and waterfilled mattresses can help a person lie in an appropriate position, relieve pressure and protect vulnerable areas from damage. Various cushions—including foam, gel, and water- or air-filled cushions—can relieve pressure and help ensure that the person is appropriately positioned in a wheelchair. Bed elevation – Hospital beds that can be elevated at the head should be raised 30 degrees. Protect the skin – Protect skin that is vulnerable to excess moisture with talcum powder and apply lotion to dry skin. Manage incontinence – Manage urinary or bowel incontinence to prevent moisture and bacterial exposure to the skin. Management may include frequently scheduled assistance with urinating, frequent diaper changes, protective lotions on healthy skin, urinary catheters or rectal tubes. Source: Mayo Clinic: www.mayoclinic.com/health/bedsores/DS00570 ASHRM Pearls for Long-Term Care details best practices for preventing pressure ulcers in bedridden and wheelchair-confined patients. Click Here to order the booklet. 7. Surgical Site Infections Recent research has found that surgical site infections (SSI) occur in 2 to 5 percent of patients undergoing inpatient surgery in the United States. Approximately 500,000 SSIs occur each year, with 75 percent of deaths among patients with SSIs directly attributable to the SSI. SSIs are classified in three categories: Superficial incisional – involving only the skin or subcutaneous tissue of the incision Deep incisional – involving fascia (connective tissue that surrounds muscles, blood vessels and nerves) and/or layers of muscles Organ/space – involving organs There are several strategies hospitals can adapt to prevent SSIs, the first being to follow existing guidelines, recommendations and requirements regarding SSIs, and develop new guidelines as needed. Other strategies include: Train infection prevention and control personnel in methods of SSI surveillance. Identify high-risk, high-volume operative procedures to be targeted for SSI surveillance. Administer antimicrobial prophylaxis on patients one hour prior to surgery in accordance with evidence-based standards and guidelines. If hair removal is necessary before surgery, remove it by clipping or using a depilatory agent; do not use a razor. Surgeons and other members of the surgical team must wear gloves and use adhesive drapes on patients. These items contribute to prevent site contamination and also reduce blood-borne pathogen transmission from patients to surgeons. Source: Journal of Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology, Strategies to Prevent Surgical Site Infections in Acute Care Hospitals: www.wsha.org/files/82/HAI-SurgicalSiteStrategies.pdf 8. Venous Thromboembolism A venous thrombosis is a blood clot (thrombus) that forms within a vein. In deep vein thrombosis (DVT) a clot breaks off and can become a life-threatening pulmonary embolism (PE). The conditions of DVT and PE are referred to collectively as venous thromboembolism. Thrombosis can occur when blood flow within the veins is slowed or blocked, the lining of the vessel wall is damaged (due to surgery or injury) or too many-blood clotting substances are present in the blood. Most deep vein clots occur in veins of the leg or pelvis. Swelling, discomfort, redness, or warmth in the legs may be the first sign of a clot forming, although in many cases there are no initial symptoms. DVT itself is not life threatening. However, if part of a clot dislodges and blocks the flow of blood to the lungs, this may cause chest pain, shortness of breath and possibly haemoptysis (coughing up of blood). A large clot in the lungs may obstruct blood circulation, causing breathlessness, dizziness or shock, and may be life threatening. Tips to prevent venous thromboembolism There are a number of medicines, mechanical therapies and surgical procedures that can be used in both the prevention and treatment of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: Anticoagulant (anti-clotting) medicines, also called "blood thinners," make the blood less able to clot, can block the formation of new clots and stop existing clots from getting bigger. Compression stockings or intermittent pneumatic compression (IPC) boots improve circulation and help to prevent DVT by increasing the speed at which blood flows through the veins in the legs. In extreme situations, surgery may be necessary to remove the blood clot or trap it so it doesn't reach the lungs. Source: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: www.ahrq.gov/qual/vtguide/ 9. Ventilator-associated Pneumonia Pneumonia is a leading cause of death due to hospital-acquired infections. Ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) is defined as pneumonia occurring more than 48 hours after patients have been intubated and received mechanical ventilation.VAP is caused by microorganisms invading the lower respiratory tract and lung parenchyma. The presence of an endotracheal tube provides a direct route for colonized bacteria to enter the lower respiratory tract. Tips to prevent VAP There are several interventions healthcare providers can use to prevent VAP. These interventions can begin before intubation and should be continued until extubation: Elevation – Elevating the head of the bed 30 to 45 degrees prevents reflux and aspiration of bacteria from the stomach into the airways and also decreases the risk for VAP. Repositioning – Routine turning of patients at a minimum of every two hours can increase pulmonary drainage and decrease the risk for VAP. Oral decontamination – Bacteria in dental plaque can be removed by brushing the teeth and thoroughly suctioning secretions from the mouth. Both of these interventions decrease the likelihood of microorganisms colonizing the oropharynx (middle part of the throat). Oral rinses – Pharmacological interventions include twice-a-day use of chlorhexidine oral rinse. Oral feeding tubes – A growing body of evidence suggests that oral feeding tubes may be better than nasal tubes in preventing VAP. Prompt extubation – The longer patients are on a ventilator the greater their risk of contracting pneumonia. Conduct daily spontaneous breathing trials and extubationreadiness assessments to determine when patients are ready for extubation. Sources: Medscape Reference: emedicine.medscape.com/article/304836-overview Clinical Microbiology Reviews, Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia: Diagnosis, Treatment and Prevention: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1592694 Critical Care Nurse, VentilatorAssociated Pneumonia: http://ccn.aacnjournals.org/content/27/4/32.full 10. Preventable Readmissions Hospital readmission rates can be an important indicator of quality of patient care. A readmission may result from incomplete treatment or poor care of the patient's underlying problem during the original/previous admission. Or it may reflect poor coordination of services at the time of discharge and an inadequate access to post discharge care. Educating patients about their aftercare is key to keeping them healthy and in preventing them from returning to the hospital. Before discharging patients, healthcare providers should ensure that these patients: Know which physician and/or clinic to contact for follow-up care Know what medications they should be taking and the correct dosages Have a reliable family member or friend who can assist them in keeping track of their aftercare directions Understand the discharge information and have a translator available to them if they do not speak English Are able to read aftercare instructions or have somebody who can read the directions for them Source: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Indentifying Potentially Preventable Readmissions: www.cms.gov/HealthCareFinancingReview/downloads/08Fallpg75.pdf