ch4-ch7-YangChen

advertisement

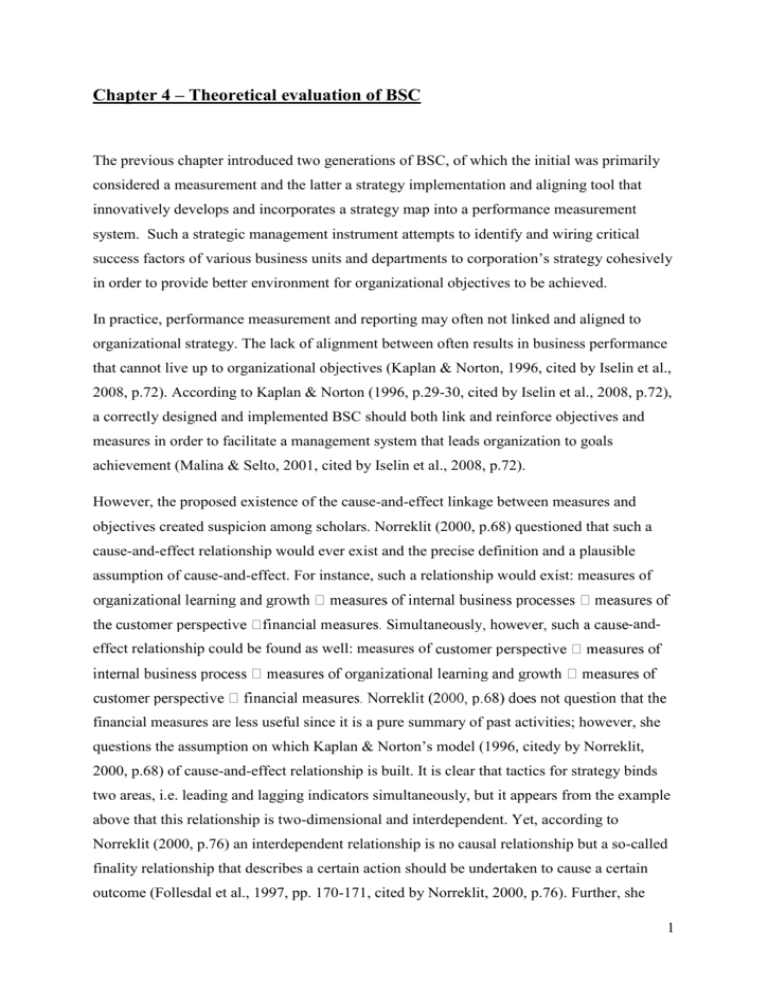

Chapter 4 – Theoretical evaluation of BSC The previous chapter introduced two generations of BSC, of which the initial was primarily considered a measurement and the latter a strategy implementation and aligning tool that innovatively develops and incorporates a strategy map into a performance measurement system. Such a strategic management instrument attempts to identify and wiring critical success factors of various business units and departments to corporation’s strategy cohesively in order to provide better environment for organizational objectives to be achieved. In practice, performance measurement and reporting may often not linked and aligned to organizational strategy. The lack of alignment between often results in business performance that cannot live up to organizational objectives (Kaplan & Norton, 1996, cited by Iselin et al., 2008, p.72). According to Kaplan & Norton (1996, p.29-30, cited by Iselin et al., 2008, p.72), a correctly designed and implemented BSC should both link and reinforce objectives and measures in order to facilitate a management system that leads organization to goals achievement (Malina & Selto, 2001, cited by Iselin et al., 2008, p.72). However, the proposed existence of the cause-and-effect linkage between measures and objectives created suspicion among scholars. Norreklit (2000, p.68) questioned that such a cause-and-effect relationship would ever exist and the precise definition and a plausible assumption of cause-and-effect. For instance, such a relationship would exist: measures of -andeffect relationship could be found as well: measures of financial measures are less useful since it is a pure summary of past activities; however, she questions the assumption on which Kaplan & Norton’s model (1996, citedy by Norreklit, 2000, p.68) of cause-and-effect relationship is built. It is clear that tactics for strategy binds two areas, i.e. leading and lagging indicators simultaneously, but it appears from the example above that this relationship is two-dimensional and interdependent. Yet, according to Norreklit (2000, p.76) an interdependent relationship is no causal relationship but a so-called finality relationship that describes a certain action should be undertaken to cause a certain outcome (Follesdal et al., 1997, pp. 170-171, cited by Norreklit, 2000, p.76). Further, she 1 pointed out that a chosen action is one out of many possible actions to achieve this outcome and may have more than just one effect (Arbnor & Bjerke, 1994, p.176, cited by Norreklit, 2000, p.76). With respect to the measures of BSC, for instance, financial success could be achieved by marketing a product of high quality, then gaining customer satisfaction and building reputation, and finally generating a higher market share and increasing profitability. In comparison to causal relationship, such definition appears to illustrate the relationship between BSC measures and perspectives better than causality, which is, according to Norreklit (2000, p.77), leaves less room for ambiguity. Building the concept on the assumption of finality, however, would have decreased the power, function and applicability of BSC significantly. Norreklit (2000, p.77) finally argues that finality would increase a tool’s complexity and reduce it to any other management technique; it appears, BSC would lose its advantage and benefit to other approaches. In her later research, Norreklit (2003) further tackled on the question of the usefulness of BSC and Kaplan & Norton’s argumentation in their published works, this time, primarily from a rhetorical aspect. She claimed that Kaplan & Norton tended to apply a style of language that is more relevant to poetry, i.e. concepts and fundamental assumptions that should have solidified the arguments for academic rigour were expressed in an emotional way, filled with metaphors and pathos (Norreklit, 2003, p.601). However, to make convincing arguments, logos rather than pathos is what suits academic and intellectual purposes (Norreklit, 2003, p.595). Another critique is the entire communicative situation in which the idea of BSC was published. A title of an internationally acknowledged professor at the most renowned business schools in the world would trigger readers to attach ethos to any arguments made and indirectly create confidence and plausibility to Kaplan’s work (Norreklit, 2003, p.598). The arguments of Norreklit (2000, 2003) generally criticises that little evidence is found on the effectiveness and function of BSC. While it might be true to argue that the usefulness of BSC is a subject of persuasion and its effectiveness has been less evidenced, BSC is still widely used among managers (De Geuser et al., 2009, p.94). In order to find evidence on its concept and effective, recent research has attempted to quantify how BSC has contributed towards business performance by testing Kaplan & Norton’s framework, firstly published in their second book “Strategy-Focused Organization” (De Geuser et al., 2009, p.95). 2 Despite a few research limitations – such as a weakly defined concept of contribution towards organizational performance and an ambiguously definition of BSC – the study generally evidences that BSC is positively correlated with performance (De Geuser et al., 2009, p.115). More specifically, BSC is described to add value to the following three points: firstly, for the translation of strategy; secondly, the potential to influence managerial behaviour; and finally, for aligning business resources to strategy. Worth mentioning is that De Geuser et al. (2009) basically did not provide the study to refute Norreklit’s perspective that finality is differently characterised from cause-and-end relationship but purely attempted to find empirical proof of the impact of BSC on organizational performance. A comparison with the 5 principles of Strategy Focused Organization in chapter 3 illustrates that principle 1, 2 and 4 can be evidenced by this study’s result; however, for principle 3 and 5, the study provides counterintuitive results. De Geuser et al. (2009, p.114) claimed, especially for the lack of relationship between executive leadership and involvement of everyone in the job of strategy formation and implementation respectively, these results may be subject to a high degree of decentralization of international corporations, i.e. determined by the characteristic of the sample. 3 Chapter 7 – Relationship between strategy and performance 7.1. VRIO framework – resource-based view (RBV) The purpose of this chapter is to build foundations for linking performance measurement, which would assist in systematically evaluating the successful cases of applying the BSC as a system for performance measurement and management control. According to Nag et al. (2007, p.946), strategic management is about the study of the plans and attempt to identify optimal plans for achieving and maintaining competitive advantage. In order to identify such plans, an organization can be looked both from the perspective of its external environment and its internal configuration. Either perspective results in the development of various methods and frameworks – such as Porter’s Five Forces, SWOT for an external, VRIO framework for an internal view (Eisenhardt et al. 2000, p.1105), each of which may differ in assumptions and arguments. Based on the definition from Nag et al. (2007, p.946),, RBV and VRIO could be ascribed to methodological attempts to formulate strategy from an internal perspective, since it originates from identifying key performance drivers – assuming that a company’s capabilities have been exploited effectively and successfully – and aims at sustaining an organisation’s competitive advantage. According to Barney (1991, p.103-104), sustainable competitive advantage necessitates the existence of two basic characteristics of firm attributes in order to become a resource – heterogeneity and immobility. Heterogeneity implies that within an industry, strategic resources may not be evenly distributed and accessible to all firms, while immobility describes the expectation that no second firm would be able to gain the same or similar resource and implement the same strategy.1 According to Grant (2001, p.126), mobility of capabilities tends to be less than that of individual resources respectively, since capability is formed upon several resources so that replicating competitors may have to lure the entire set of resources and incorporate it in the same way in order to complete the strategy. 1 Wernerfelt (1984, cited by Rugman et al., 2002, p.771) contended that the Edith Penrose’s contribution towards the formation of the concept of RBV is immeasurable; her “…idea of looking at firms as a broader set of resources goes back to the seminal work of Penrose’ and the optimal growth of the firm involves a balance between exploitation of existing resources and development of new ones”. 4 Building on these two assumptions – heterogeneity and immobility – Barney (1991, p. 105111) extended the concept of RBV and developed the VRIO framework which summarizes the following four characteristics of strategic resources: valuable – rare – inimitable – organization. A strategic resource rendering competitive advantage, according to Barney (1991, p.106), needs to be on top of all other characteristics valuable, i.e. it assists the firm in initiating strategy which in turn reduces its threat in the external environment. In that sense, a given firm in an industry, regardless of threats from market incumbents or new entrants, in possession of such valuable resources will be capable of neutralizing (Barney, 1991, p.106) the source of threat. When a firm manages to implement a strategy that is not easily conceived by a large number of competitors exploiting the same resource this company benefits from a source of competitive advantage. In other words, a valuable and rare resource protects the firm from competition dynamics in an industry (Hirshleifer, 1980, cited by Barney, 1991, p.107). It is the inability of competitors to emulate the same strategic resource not the time frame within which the rareness of such a resource might fade; in Barney’s words (1991, p. 102-103), the equilibrium between owners of strategic resources and non-owners defines whether or not a resource is rare and strategically relevant to offer competitive advantage. ‘Imperfectly imitable’ or inimitable resources pose another barrier for competitors from benefiting from competitive advantage and reaping above-average profits. The presence of such inimitable resources is subject to the following (Barney, 1991, p.107): - Historical conditions: RBV opposes the assumption, mostly supported by Porter (1980, cited by Barney, 1991, p.107), that unique history or certain distinctive attributes have no impact on a firm’s performance. In contrast, RBV advocates support the opinion of traditional strategy researchers such as Ansoff (1965) and reiterate that a firm’s long term performance is indeed determined by the firm’s founding and unique circumstances, especially those firms which have gained possession and control over ‘idiosyncratic attributes’ through its origination, growth and development will be more probable to sustain such sources of competitive advantages. - Causal ambiguity: Unlike to relationship between inimitability and historical conditions, the relationship between causal ambiguity and imperfect imitability 5 describes subtleness of firm’s attributes that form the setting of competitive advantage, i.e. the link between organizational activities can hardly be defined and “relocated” to other competitors in order to accomplish the same potential for performance. Barney (1991, p. 109) and Lippman & Rumelt (1982) are even of opinion that even the respective company itself may not understand its source for success, i. e. all industry incumbents and entrants may not clarify, understand and control the linkage of such actions, otherwise the dissipation of critical information will eliminate at least one of the two fundamental assumptions of RBV – heterogeneity. When comparing Barney’s VRIO framework to the theory RBV of Grant (2001, p.126), causal ambiguity is similar to transparency in Grant’s understanding. One source of non-transparency is that various capabilities may interdepend and interrelate across several performance determining factors. Another cause for non-transparency is the coordination and intertwining of a large number of resources simultaneously, thus complicating the pattern for successful strategy implementation. - Social complexity:…is the fourth factor that reduces imitability may result from organizational culture, structure, traditions that positively complement other organizational resources and capabilities, thus promote such advantages to be exploited (Barney, 1991, p.110). Even when competitors may have the same technology at availability, the lack of those social determinants will pose impediments to initiate an equally successful strategy (Wilkins, 1989, cited by Barney, p.110). The ‘O’ in VRIO signals organization. It summarizes all possible and available attributes to create a fertile internal environment that allows strategic resource to be availed effectively. Such an environment may blend factors ranging from organizational culture, structure, human capital, funding etc. (O’Riordan, 2006, p.43). The list of examples is non-exhaustive and may adopt new types of resources and capabilities that have been upgraded in order to conquer radical and rapid changes in business environment. 7.2. Linking strategy to performance measurement Although, at first glance, strategy and performance measurement do not have much in common, the previous chapter on BSC and the development of its various generations has successfully attempted to solidify the foundations for linking those two seemingly separated disciplines together. In fact, according to some sociology specialists, strategic management is 6 about the “…study of firms’ performance from a platform of tangible and intangible resources in an evolving environment that includes their market and value network…” and it could be argued additionally that strategic management supports an organization’s management to comprehend the causal relationship between its strategic choices and performance, which is understood more than just profitability and includes capability of innovation and survival (Nag et al., 2007, p.946). This definition, derived from the study of Nag et al., partly explains the importance of performance measurement for strategy formation and implementation. The strategic management process encompasses, according to Olson & Slater (2002, p.11), five related components, ranging from the analysis of organization to formulation of its competitive strategy, whereby strategy is completed by the supervision of performance in order to foster organizational feedback and learning procedures. The indicators integrated into the design of and those sources of information gained through performance measurement systems are well needed both for internal communication and demonstration to external stakeholders. In particular, organizational functions such as marketing, finance department’s objectives are less recommended to stick to an organization’s operational level only but related to that firm’s business level strategy. Successfully linking functional objectives to organizational ones enables performance measurement to evolve as an effective tool used for strategy formation and strategic decision making (Micheli & Manzoni, 2009, p.472-473). In this paper, RBV and the related VRIO framework has been selected to analyze several organization’s potential for creating and sustaining competitive advantage. In order to back up practical examples and an appropriate analysis of case studies in subsequent chapters, it is necessary to holistically understand the association between RBV and performance measurement. In her empirical study of 107 companies across non-manufacturing and manufacturing industries, Widener (2006, p.433) investigated: firstly, manager’s perception and evaluation of various types of performance measures and firms’ strategic resources that maintain the sustainability of competitive advantage; and secondly, whether performance measures function as connectors between strategic resources and performance. The overall result of her structural equation model indicates a certain degree of importance of using performance measures for mediating the connection between strategic resources and firm performance. More specifically, empirical evidence supports the argument that 7 performance in non-manufacturing firms is stronger associated with the importance placed on human capital than that associated with the importance placed on other resources (Widener, 2006, p.437), i.e. structural such as knowledge (Amit & Schoemaker, 1993, cited by Widener, 2006, p.434) and physical capital such as geographic locations and other fixed assets (Barney, 1991, cited by Widener, 2006, p.433). Often stated in the in literature of performance measurement and management is “what gets measured gets done”. This general concept indicates two aspects of performance measurement for management control and strategic management process. One is that the choice of performance measures can trigger various behaviors; when the “right” choice of measures is made, behaviors are conducted into the “right” direction towards business success (Olson & Slater, 2002, p.15; Kaplan & Norton, 1992, p.172). The other aspect intuitionally follows from the fact that different strategies require different factors for success. In order to reveal and properly manage such “critical success factors”, the design of performance measurement system and the choice of multiple types of performance measures should be tailored to strategic resources that nurture a firm’s strategy orientation, thus building the ground for competitive advantage and business success (Olson & Slater, 2002, p.15; Simons, 2000; Kaplan & Norton, 1996; Amit & Schoemaker, 1993, cited by Widener 2006, p.434). In other words, subject to the power of such strategic resources in supporting a firm’s strategy, it is necessary for managers to customize the organization’s performance measurement and also measure the effect of strategic resources (Simons, 2000, cited by Widener, 2006, p.437). For this purpose, Widener further came up with two other hypotheses which have been supported by empirical results. There is association between manager’s assessment of selecting certain performance measures and the emphasis on certain strategic measures. In particular, the results of her study support the view that, in non-manufacturing businesses, the evaluation of structural capital and non-traditional measures (e.g. productivity, operational measures and employee) are more strongly associated. This outcome further implies that, in non-manufacturing companies, the importance placed on structural capital is positively related to that placed on human capital in terms of training, skills development etc. (Widener 2006, p.451). Moreover, the third hypothesis of her study supports the view that a firm’s management perception of the use of strategic resources and performance is mediated by the importance of 8 the use of performance measures. The link created by performance measures is most significantly evident in non-manufacturing companies, of which, when importance is devoted to human capital, management also chooses performance measures related to employee satisfaction and operations. Consequently, those companies achieve a significantly higher performance (Widener 2006, p.453). In conclusion, the study, in spite of the limitation that it has not been able to investigate research on all potential performance measures, strategic resources (Widener, 2006, p.454), provides some essential insights into the importance of performance measures that have a positive impact on firm’s performance, whereby those measures are considered linkages between performance and strategic resources. 7.3. Linking strategy to Balanced Scorecard (BSC) Initially emerged as a management instrument to link various different measures of performance with each other in order to foster managerial attention onto business’s critical areas (Kaplan & Norton, 1992, p.172), the BSC further reinforces its usefulness for creating a causal relationship between performance measures and business level strategy. As previously described, the BSC locates the essence of strategy in the form of “vision & mission” (Kaplan & Norton, 1992, p.180), and builds several paths towards these four different perspectives: customer, internal processes, learning & growth and financial, of which the first and the last one are considered “lagging” indicators and the rest “leading” ones. Building upon the structure of the first generation of BSC in 1992, Kaplan & Norton investigated into the technique of implementation in 200 companies and detected that the starting point for setting up an appropriate “environment” for BSC shall be the company’s strategy. It forms the core of their strategy map, which describes a logical sequence of business activities across the four perspectives from above and helps clarify some previously hidden linkages and cause-and-effect relationship between stages of actions (Kaplan & Norton, 2001, p.90). The following exhibit lists Kaplan & Norton’s suggestion of critical elements: 9 Critical elements and their linkages for strategy Shareholder value – enhanced by growth and productivity Market share, acquisition, retention of target customers – encouraged by profitable growth Higher-margin businesses – requires customer value propositions Value propositions – delivered by excellence in innovation, products and services to target customers Sustainable growth – maintained by investment in human capital and systems Source: Kaplan & Norton, 2001, p.90 Unlike to original form of BSC that is intended to combine long-term strategic objectives to short-term activities (Ittner & Larcker, 1998, p.223) the “new” BSC accompanied by a strategy map aims at focusing on a firm’s strategic orientation and thus, in Kaplan & Norton’s words, on the “future”. In contrast to Ittner & Larcker who tended to describe the BSC as a measurement tool, Kaplan & Norton observed the use of BSC in practice more as a management system (Kaplan & Norton, 2001, p.102). Moreover, the newer BSC intends to offer the potential for detecting an organization’s dynamic capabilities which intend to meet new organizational strategy. According to RBV specialists, dynamic capabilities build on a firm’s related system of activities that derive from antecedent routines and existing resources and competencies configured in a new way to accomplish value-creating strategies and meet new market specifications (Collis & Montgomery, 1995, 1998; Porter, 1996; core competencies, Prahalad & Hamel, 1990; cited by Eisenhardt & Martin, 2000, p.1107). This potential of dynamic capabilities to create new value-generating strategies is integrated into a firm’s processes, which, in turn, catalyze a procedure of synthesizing, acquiring and upgrading to reconfigure resources in a new way (reconfigure, Teece et al., 1997; synthesize, Kogut & Zander, 1992; cited by Eisenhardt & Martin, 2000, p.1107). The same power that dynamic capabilities offer is indeed embedded in the new BSC Kaplan & Norton described. Along the process of communicating and transforming strategy into a system of interrelated measures, the focus of an organization is driven to resources and capabilities an organization possesses and newly detects, while stimulating the old organization to unfreeze assets and capabilities and guarantee the sustainability for long-term value creation (Kaplan & Norton, 2001, p.102) and competitive advantage. 10 11 Source: Kaplan & Norton, 2001, p.92 The Balanced Scorecard Strategy Map Beyond attributing a new definition to existing resources and capabilities, reconfigured and integrated into the firm’s routines – which primarily encompass internal processes and learning & growth perspective, BSC further, building on the presence of such dynamic capabilities, redefines the firm’s relationship to its external stakeholders, represented mostly by customers and stakeholders. Such a way of strategy communication and transformation creates the potential for firms to balancing its devotions to the “stakeholders” of internal and external parties, while integrating and linking all possible units (Kaplan & Norton, 2001, p.102) of those parties to organizational strategy. The previous exhibit displays a template of the “strategy map” by Kaplan & Norton (2001, p. 92). The chapter on cases review will apply this instrument for a critical evaluation of the successfulness of BSC implementation. 12