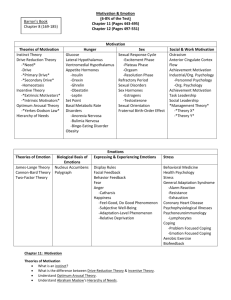

Motivation and Emotion: Summary of Key Concepts

advertisement

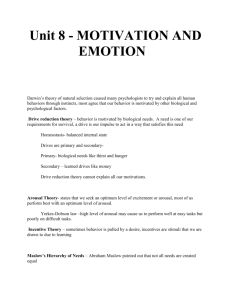

Perspectives on Motivation and Emotion Replacing the power point notes with this summary of the motivation and emotion chapter. Motivation is … 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. the energizing and directing of behavior the force behind our yearning for food our longing for sexual intimacy our need to belong our desire to achieve. Instincts and Evolutionary Psychology Under Darwin’s influence, early theorists viewed behavior as controlled by biological forces, such as specific instincts. When it became clear that people were naming, not explaining, various behaviors by calling them instincts, this approach fell into disfavor. The underlying idea—that genes predispose species-typical behavior—is, however, still influential in evolutionary psychology. Drive reduction theory 1. states that most physiological needs create aroused psychological states, driving us to reduce or satisfy those needs. 2. The aim of drive reduction is internal stability, or homeostasis 3. Drive reduction motivates survival behaviors, such as eating and drinking. Not only are we pushed by our internal drives, we are also pulled by external incentives. Depending on our personal experiences, some stimuli (for example, certain foods) will arouse our desires. Optimum Arousal 1. Rather than reducing a physiological need or tension state, some motivated behaviors increase arousal. 2. Curiosity-driven behaviors, for example, suggest that too little as well as too much stimulation can motivate people to seek an optimum level of arousal. A Hierarchy of Motives – Maslow 1. Until satisfied, some motives are more compelling than others. It indicates that… a. physiological needs must first be met b. then safety c. followed by the need for belongingness and love, d. esteem needs. e. Once all of these are met, a person is motivated to meet the need for selfactualization. This order of needs is not universally fixed but it provides a framework for thinking about motivation. Hunger - The Physiology of Hunger 1. Hunger’s inner push primarily originates not from the stomach’s contractions but from variations in body chemistry, including hormones that heighten or reduce hunger. For example, we are likely to feel hungry when our glucose levels are low or when ghrelin is secreted by an empty stomach. This information is integrated by the hypothalamus, which regulates the body’s weight as it influences our feelings of hunger and satiety. To maintain weight, the body also adjusts its metabolic rate of energy expenditure. Hunger - The Psychology of Hunger 1. Our preferences for certain tastes are partly genetic and universal, but also partly learned in a cultural context. For example, the impact of psychological factors, such as challenging family settings and weight-obsessed societal pressures, on eating behavior is dramatic in people with anorexia nervosa, who keep themselves on near-starvation rations, and in those with bulimia nervosa, who binge and purge in secret. 2. A dramatic increase in poor body image has coincided with a rise in eating disorders among women in Western cultures. In addition to cultural pressures, low self-esteem and negative emotions (with a possible genetic component) seem to interact with stressful life experiences to produce anorexia and bulimia. Sexual Motivation - The Physiology of Sex 1. Physiologically, the human sexual response cycle normally follows a patternof… a. excitement, plateau, orgasm, and resolution b. followed in males by a refractory period, during which renewed arousal and orgasm are impossible. c. Sex hormones, in combination with the hypothalamus, help our bodies develop and function as either male or female. d. In nonhuman animals, hormones also help stimulate sexual activity. e. In humans, they influence sexual behavior more loosely, especially once sufficient hormone levels are present. Sexual Motivation - The Psychology of Sex 1. External stimuli can trigger sexual arousal in both men and women. 2. Sexually explicit materials may also lead people to perceive their partners as comparatively less appealing and to devalue their relationships. 3. In combination with the internal hormonal push and the external pull of sexual stimuli, fantasies (imagined stimuli) influence sexual arousal. 4. Sexual disorders, such as premature ejaculation and female orgasmic disorder, are being successfully treated by new methods, which assume that people learn and can modify their sexual responses. Adolescent Sexuality 1. Adolescents’ physical maturation fosters a sexual dimension to their emerging identity. 2. Culture is a big influence, as is apparent from varying rates of teen intercourse and pregnancy. 3. A near-epidemic of sexually transmitted infections has triggered new research and educational programs pertinent to adolescent sexuality. Sexual Orientation 1. One’s heterosexual or homosexual orientation seems neither willfully chosen nor willfully changed. 2. Preliminary new evidence links sexual orientation with genetic influences, prenatal hormones, and certain brain structures. 3. The increasing public perception that sexual orientation is biologically influenced is associated with increasing acceptance of gays and lesbians and their relationships. Sex and Human Values 1. Sex research and education are not value-free. 2. Some say that sex-related values should therefore be openly acknowledged, recognizing the emotional significance of sexual expression. 3. Human sexuality at its life-uniting and love-renewing best affirms our deep need to belong. The Need to Belong 1. No one is an island; we are all, as John Donne noted in 1624, part of the human continent. 2. Our need to affiliate—to feel connected and identified with others—boosted our ancestors’ chances for survival and is therefore part of our human nature. 3. We experience our need to belong when suffering the breaking of social bonds, when feeling the gloom of loneliness or the joy of love, and when seeking social acceptance. 4. For people experiencing ostracism, stress and depression can result. On the other hand, people who feel a sense of belongingness are happier and healthier. Motivation at Work 1. For most people, work is a huge part of life. At its best, when work puts us in "flow," work can be satisfying and enriching. 2. What, then, enables worker motivation, productivity, and satisfaction? Personnel Psychology/Harnessing Strengths 1. Personnel psychologists aim to identify people’s strengths and to match them with organizational tasks. 2. Subjective interviews lead to quickly formed impressions, but they also frequently foster an illusory overconfidence in one’s ability to predict employee success. 3. Structured interviews, pinpointing job-relevant strengths, enhance interview reliability and validity. 4. Personnel psychologists also assist organizations in appraisal that boosts organizations, motivates individuals, and is welcomed as fair. Organizational Psychology: Motivating Achievement 1. People who excel are often self-disciplined individuals with strong achievement motivation. 2. To motivate employees to achieve, smart managers aim to create an engaged, committed, satisfied workforce. 3. Effective leaders build on people’s strengths, work with them to set specific and challenging goals, and adapt their leadership style to their situation. Perspectives on Emotion Emotion is made up of three components 1. physiological arousal 2. expressive behaviors 3. conscious experience. One of the oldest theoretical controversies regarding emotion focuses on the timing of our feelings in relation to the physiological responses that accompany emotion. Theories of Emotion 1. William James and Carl Lange: proposed that we feel emotion after we notice our physiological responses. 2. Walter Cannon and Philip Bard: believed that we feel emotion at the same time that our bodies respond. 3. Schachter-Singer two-factor theory: focuses on the interplay of the emotions rather than the timing of the emotions. It states that there are only two components of emotion – a. physical arousal b. cognitive label Emotions and the Autonomic Nervous System 1. Emotions are both psychological and physiological. 2. Much of the physiological activity is controlled by the autonomic nervous system’s sympathetic (arousing) and parasympathetic (calming) divisions. \ 3. Our performance on a task is usually best when arousal is moderate, though this varies with the difficulty of the task. Physiological Similarities Among Specific Emotions 1. Three emotions—fear, anger, and sexual arousal—produce similar physiological responses that are nearly indistinguishable to an untrained observer. However, the emotions are felt differently by those experiencing them. Physiological Differences Among Specific Emotions 1. Emotions stimulate different facial muscles. 2. Additionally, scientists have discovered subtle differences in activity in the brain’s cortical areas, in use of brain pathways, and in secretion of hormones associated with different emotions. Thinking and Emotion 1. A spillover effect occurs when our arousal response to one event spills over into our response to the following event. 2. Arousal fuels emotion; cognition channels it. 3. Emotional responses are immediate when sensory input goes directly to the amygdala via the thalamus, bypassing the cortex, triggering a rapid reaction that is outside our conscious awareness. Nonverbal Communication 1. Much of our communication is through the body’s silent language. 2. Psychologists have studied people’s abilities to detect emotion, even from thin slices of behavior. 3. Research has found that women are typically more sensitive to nonverbal clues than men. Detecting and Computing Emotion 1. Discerning lies from truth is difficult for the untrained eye. 2. There are certain professionals who are more skilled at detecting emotion. 3. Researchers are studying the role of nonverbal communication during job interviews. 4. In E-mail communications, nonverbal cues are missing which can lead to misinterpretation. Culture and Emotional Expression 1. Although some gestures are culturally determined, facial expressions, such as those of happiness and fear, are common the world over. 2. In communal cultures that value interdependence, intense displays of potentially disruptive emotions are infrequent. The Effects of Facial Expressions 1. Expressions do more than communicate emotion. They also amplify the felt emotion and signal the body to respond accordingly. 2. Emotions, then, arise from the interplay of cognition, physiology, and expressive behaviors. Experienced Emotion 1. Among various human emotions, we looked closely at how we experience three: fear, anger, and happiness. a. Fear - Fear is an adaptive emotion, but it can be traumatic. Although we seem biologically predisposed to acquire some fears, what we learn through experience and observation best explains the variety of human fears. b. Anger - Anger is most often evoked by events that not only are frustrating or insulting but also are interpreted as willful, unjustified, and avoidable. Blowing off steam may be temporarily calming, but in the long run it does not reduce anger. Expressing anger can actually make us angrier. c. Happiness - A good mood boosts people’s perceptions of the world and their willingness to help others. The moods triggered by the day’s good or bad events seldom last beyond that day. Even significant good events, such as a substantial rise in income, seldom increase happiness for long. We can explain the relativity of happiness with the adaptation-level phenomenon and the relative deprivation principle. Nevertheless, some people are usually happier than others, and researchers have identified factors that predict such happiness.