literature-review-end-of-life-care-in-the-icu-the

advertisement

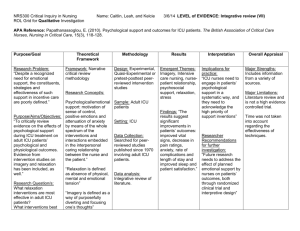

Literature Review: End-of-Life Care in the ICU: The Impact of Nursing Care on the Spiritual and Religious Needs of Patients and Families Kristi Bruno DePaul University March 13, 2015 Literature Review: End-of-Life Care in the ICU: The Impact of Nursing Care on the Spiritual and Religious Needs of 2 Patients and Families Time spent in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) can be a stressful, emotionally draining, and often-traumatic experience for both patients and families. Patients are often unable to communicate independently due to patient sedation, intubation, or respiratory ventilation (Hupcey, 1998), and families are forced to provide surrogate decision making on the patient’s behalf. Families may also be put in a position to make end-of-life decisions on the patient’s behalf—sometimes without expressly knowing the patient’s desires due to lack of end-of-life planning and documentation (Wall, Engelberg, Gries, Glavan & Curtis, 2007). This gray area causes distress and potential disagreement for families. Many families are in need of spiritual and religious support during these stressful times and religion plays a large role in decision-making and the end-of-life. Research has shown that many clinicians undervalue or are not prepared to support the religious and spiritual needs of an ICU patient’s family (Wall, et al., 2007). The literature has also revealed that religious beliefs of the healthcare team, namely physicians, can cloud the decisions made around the care of the patient. Nurses play a unique role in the care of an ICU patient, as he or she may be providing around-the-clock care of the patient who is in critical condition. With limited ability to communicate directly with the patient, the focus from nursepatient relationship shifts to nurse-family relationship (Hupcey, 1998). The intimate 2 Literature Review: End-of-Life Care in the ICU: The Impact of Nursing Care on the Spiritual and Religious Needs of 3 Patients and Families relationship that evolves between the patient, family, and nurse holds a great deal of potential to meet the unmet spiritual and religious needs of families of ICU patients. Spirituality and Religion The terms spirituality and religion are often used interchangeably, but have inherently different meanings. “Religion has been associated with various connotations: the totality of belief systems, an inner piety or disposition, an abstract system of ideas, and ritual practices” (Wulff, 1997). Spiritualty can be a component of religion, but can also stand alone. A widely accepted definition of spirituality in the healthcare setting interprets spirituality as “constructs of meaning or a sense of life’s purpose” (Fitchett & Handzo, 1998). Both the religious and spiritual beliefs of the patient and clinician can impact end-of-life decisions and care. Much research has been conducted about the role of religion of the clinician, as well as the role of religion in the patient and family. Bülow and colleagues explored clinician religion, end-of-life decisions, and patient autonomy in the ICU. This study found that many healthcare professionals desired less treatment than patients and family members. They also found that religious affiliation of the clinician did impact the beliefs around life-prolonging treatment and euthanasia (Bülow, et al, 2012). These religious beliefs may unintentionally impact the care the 3 Literature Review: End-of-Life Care in the ICU: The Impact of Nursing Care on the Spiritual and Religious Needs of 4 Patients and Families patient receives, which may or may not align with the patient’s religious beliefs (Sprung, et al, 2007). In a 2012 editorial, Dee W. Ford notes that in general, religious individuals choose more aggressive ICU care, and use of a faith-based psychological coping mechanism led patients to increase the use of ICU therapies prior to death. Interestingly, religious ICU patients and families reported more optimism in the face of critical illness in the ICU, and felt treatments would be more effective. Being active in a religious organization often led to more community and family support during times of illness, which often equated to more aggressive care (Ford, 2012). Care teams for ICU patients ideally contain a chaplain, pastor or other social worker trained to help address the spiritual needs of patients. While clinicians are not obligated to provide spiritual or religious care to patients and families, they do hold the responsility of providing a spiritual assessment of the patient and potential referral to another team member specially trained to give spiritual care (Sulmasy, 2002). Wall and colleagues conducted a cross-sectional study which surveyed families of patients who had died in the ICU or who had died within 24 hours of discharge and asked them to rate several factors including overall satisfaction with the ICU care their loved ones received, but also their satisfaction with spiritual care. Family members were more likely to rate their spiritual care positively, as opposed to leaving the question blank, if a pastor or spiritual advisor was involved in the last 24 hours of the patient’s life. Family members who were more satisfied with their 4 Literature Review: End-of-Life Care in the ICU: The Impact of Nursing Care on the Spiritual and Religious Needs of 5 Patients and Families spiritual care also rated their overall satisfaction with the ICU care at a higher level (Wall, et al., 2007). A gap in the literature exists in the area of best practices in end-of-life care and spiritualty of patients in the ICU. Many studies give great detail around the care of patients and families in a hospital or hospice setting, but there may be less evidence due to the unique paths and shorter duration of stay of ICU patients at the end of life. Much of the focus of the care team focuses on life-sustaining treatments and many spiritual needs may be perceived as less important and go unmet (Wall, et al, 2007). Unique Role of ICU Nurses As nurse-patient relationships shift to nurse-family relationships in the ICU, nurses begin to provide care to the patient with most directives coming from surrogate decision-making family members. Throughout this delicately balanced time comes a give and take between nurses and families. Nurses encounter several obstacles in treating patients including serving as a main connection for family members who are calling the ICU phone line for updates on loved ones, which in turn takes away from time to care for the patient, families misunderstanding the term “life-saving measures,” and physician disagreement about the treatment plan for the patient (Beckstrand & Kirchoff, 2005). 5 Literature Review: End-of-Life Care in the ICU: The Impact of Nursing Care on the Spiritual and Religious Needs of 6 Patients and Families Families operating under a great deal of stress often develop coping mechanisms for managing the nurse-family relationship. Some mechanisms are positive such as determining, by observation, if the nurse is a “good” nurse or not, making overtures, and displaying trust. Nurses were found to build family relationships by demonstrating commitment to the patient and family, getting to know the family and patient, being involved with the care of the patient, and breaking rules such as visiting hours or number of visitors allowed. Hupcey also found that “by virtue of the ICU situation, most families attempted to develop a relationship with the nurses because they felt that it would help the patient.” (Hupcey, 1998). Having this knowledge and understanding this perspective can help the nurse to build trust with the patient and family. Additional research also indicated the actions of nurses were strongly associated with a patient feeling safe, hopeful and peaceful (Hupcey, 2000). Beckstrand and Kirchoff found that many of the most highly scored supportive behaviors in ICU care were actions the nursing team was able to directly impact, including allowing families adequate time with the patient after death, providing a dignified scene around the time of death, and teaching patients’ families how to behave around a dying patient (Beckstrand & Kirchoff, 2005). 6 Literature Review: End-of-Life Care in the ICU: The Impact of Nursing Care on the Spiritual and Religious Needs of 7 Patients and Families In a study by Beckstrand and colleagues, critical care nurses were surveyed on end-of-life care and the idea of providing a “good death” surfaced repeatedly. Nurses felt a good death included the patient having his or her dignity in tact at the time of death, peace, not being alone at death, pain management, avoiding futile care, communication, and respecting the wishes of the dying patient (Beckstrand, et al, 2006). Several of these elements address the patient as a whole being, and focus less on standard medical approaches as the patient neared the end of life (Sulmasy, 2002). Discussion Several themes existed throughout the literature including the need for additional end-of-life support for patients and families. Families expressed interest and need for more focus on religious and spiritual needs. Much of the research points to the potential role nurses could play in this critical element of end-of-life care. There is also a place for critical health literacy, confrontation of disparities, and culture-centered approach to improve the end-of-life experience. Families noted important factors in the care of a loved one included shared decision making, family meetings and inclusion in rounding on patients the medical team, and allowing family to be present at the time of death. (Hinkle, Bosslet & Torke, 2015). In a study of the spiritual needs of dying patients, families and 7 Literature Review: End-of-Life Care in the ICU: The Impact of Nursing Care on the Spiritual and Religious Needs of 8 Patients and Families patients also noted several strategies to address spiritual care and the end of life. Those strategies include arrangement of patient rooms so patients are able to view outdoors, providing time and space for religious practice, and shared decision making (Hermann, 2001). These tasks could be directly managed and implemented by a patient’s nursing team. It should be noted that several instances in the literature alluded to challenges in providing good end-of-life care. Recurring themes include lack of time to complete detailed end-of-life tasks, staffing patterns, lack of individual care at the time of death, communication challenges, treatment decisions based on the opinions and beliefs of the physician rather than the patient, and more experienced nurses being pulled from dying patients to more clinically-complicated patients (Beckstrand, Clark, Callister & Kerchoff, 2006). Hospital administrators and critical care leaders should pay special attentions to these issues. While they are multilayered and often hard to solve, awareness of the issues and forums to address the problems should be made available. Health literacy could also play a part in improving the patient and family experience of end-of-life care in the ICU. The literature referenced the use of futile care as one of the barriers to providing good end-of-life care, and individuals with deeply religious views were more likely to engage in unfounded futile care. Public health literacy can inform, educate, and empower people about health issues 8 Literature Review: End-of-Life Care in the ICU: The Impact of Nursing Care on the Spiritual and Religious Needs of 9 Patients and Families (Gazmararian, Curran, Parker, Bernhardt & DeBuono) and perhaps provide perspective on the potential downfalls of employing futile care in the ICU while still being sensitive to the spiritual and religious views of the patient. As clinicians work to provide the best care possible, it should also be noted that religious disparities such as the role of bias, discrimination, and stereotyping by providers, patients, institutions, and health systems (Nelson, 2002) be acknowledged and worked through by the care team. Just as racial and ethnic disparities exist, as our country becomes more and more diverse, it will be important for clinicians to be aware of and responsive to the spiritual and religious needs of a diverse patient base. There may also be more opportunities, outside methods already employed, such as family surveys after ICU care, to engage families of patients who passed away in the ICU in a culture-centered approach. By involving these families, solutions may be found at several levels that can impact the care of patients and families in the future (Dutta, Jones, Borron, Anaele, Gao & Kandukuri, 2013). Conclusion The literature has revealed that spiritual and religious care are an integral part of end-of-life care, and it is not clear that there is any kind of wide spread protocol or method of providing this type of care within an ICU setting. There is also 9 Literature Review: End-of-Life Care in the ICU: The Impact of Nursing Care on the Spiritual and Religious Needs of 10 Patients and Families a distinct gap within the research outlining the spiritual and religious needs of patients and families in the ICU, likely due to the varied and quickly deteriorating path of individual patients. Research in the area of meeting the needs of dying patients in a hospital or hospice setting are available, but the literature is lacking in the area of ICU spiritual and religious care. Research suggests that nurses may play a key role in ensuring patients and families receive the care they need. Barriers exist in time, resources, and expertise to ensure good care. Training of the entire medical team is needed, and clear communication and action plans presented both verbally and in written form are needed for successful implementation. Nurse leaders may play a key role in managing this care within the ICU, and there may be a role for further study and recommendations from thought leaders from organizations such as the Association of Critical-Care Nurses and other organizations providing end-of-life care in the ICU. Proper spiritual and religious care should be a major focus of healthcare systems, and these systems should strive for a high level of cultural competence. “Culturally competent health care system—one that acknowledges and incorporates—at all levels—the importance of culture, assessment of crosscultural relations, vigilance toward the dynamics that result from cultural differences, expansion of cultural knowledge, and adaptation of services to meet culturally unique needs” (Betancourt, Green, Carrillo, AnanehFirempong, 2003). 10 Literature Review: End-of-Life Care in the ICU: The Impact of Nursing Care on the Spiritual and Religious Needs of 11 Patients and Families Additionally, as suggested by both Sumpter and Carthon, and Hupcey, simply raising awareness of desired behaviors and actions of the healthcare team, and providing a forum for discussion and analysis might be a good place to begin. Heightened awareness could significantly improve the spiritual and religious endof-life experience for patients and families in the ICU (Hupcey, 1998. Sumpter & Carthon, 2011). 11 Literature Review: End-of-Life Care in the ICU: The Impact of Nursing Care on the Spiritual and Religious Needs of 12 Patients and Families References Betancourt, J., Green, A., Carrillo, J., & Ananeh-Firempong, O. (2003). Defining cultural competence: A practical framework for addressing racial/ethnic disparities in health and health care. Public Health Reports, 118, 293-302. Beckstrand, R., Clark Callister, L., & Kirchoff, K. (2006). Providing a "good death": Critical care nurses' suggestions for improving end-of-life care. American Journal of Critical Care, 15(1), 38-45. Beckstrand, R. & Kirchoff, K. (2005). Providing end-of-life care to patients: Critical care nurses' perceived obstacles and supportive behaviors. American Journal of Critical Care, 14(5), 395-403. Bülow, H., Sprung, C., Baras, M., Carmel, S., Svantesson, M., Benbenishty, J., ... Nalos, D. (2012). Are religion and religiosity important to end-of-life decisions and patient autonomy in the ICU? The Ethicatt study. Intensive Care Medicine, 38, 1126-1133. Dutta, M., Jones, C., Borron, A., Anaele, A., Goa, H., & Kandukuri, S. (2013). Voices of Hunger: A Culture-Centered Approach to Addressing Food Insecurity. In 12 Literature Review: End-of-Life Care in the ICU: The Impact of Nursing Care on the Spiritual and Religious Needs of 13 Patients and Families Reducing Health Disparities: Communication Interventions (Vol. 6, pp. 479495). New York: Peter Lang. Fitchett, G. & Handzo, G. (1998). Spiritual assessment, screening, and intervention in: Holland JC ed, Psycho-oncology. New York, NY. Oxford Press University, 790-808. Gazmararian, J., Curran, J., Parker, R., Bernhardt, J., & Debuono, B. (2005). Public Health Literacy In America An Ethical Imperative. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 28(3), 317-322. Hermann, C. (2001). Spiritual needs of dying patients: a qualitative study. Oncology Nursing Forum, 28(1), 67-72. Hinkle, L., Bosslet, G., & Torke, A. (2015). Factors Associated With Family Satisfaction With End-of-Life Care in the ICU. CHEST, 147(1), 82-93. Hupcey, J. (1998). Establishing the nurse-family relationship in the intensive care unit. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 20(2), 180-194. Hupcey, J. (2000). Feeling Safe: The Psychosocial Needs of ICU Patients. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 361-367. 13 Literature Review: End-of-Life Care in the ICU: The Impact of Nursing Care on the Spiritual and Religious Needs of 14 Patients and Families Nelson, A. (2002). Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Journal of the National Medical Association. 94(8). Sprung, C., Maia, P., Bulow, H., Ricou, B., Armaganidis, A., Baras, M., ... Thijs, L. (2007). The Importance Of Religious Affiliation And Culture On End-of-life Decisions In European Intensive Care Units. Intensive Care Medicine, 33, 1732-1739. Sumpter, D., & Carthon, J. (2011). Lost in Translation: Student Perceptions of Cultural Competence in Undergraduate and Graduate Nursing Curricula. Journal of Professional Nursing, 27, 43-49. Wall, R., Engelberg, R., Gries, C., Glavan, B., & Curtis, J. (2007). Spiritual Care Of Families In The Intensive Care Unit*. Critical Care Medicine, 35(4), 10841090. Wulff, D. (1997) Psychology of Religion: Classic and Contemporary. New York, NY; John Wiley & Sons. 14