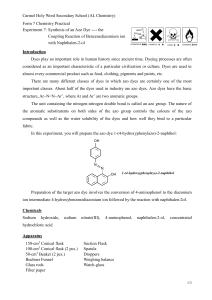

Options to Limit Consumer Exposure to Hazardous Azo Dyes in

advertisement