Squabble Disrupts a Refuge for the Rich

advertisement

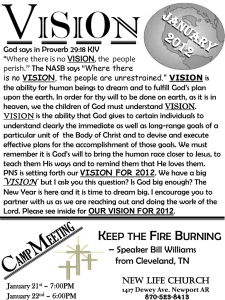

Squabble Disrupts a Refuge for the Rich Ryan Conaty for The New York Times The Vanderbilt family’s “cottage” in Newport, R.I., draws 400,000 visitors a year. A proposal to build a visitors center on the grounds is raising hackles. NEWPORT, R.I. — Change has rarely been welcomed in this seaside haven of the uber-rich, where the famously over-the-top mansions of the Gilded Age are still called “cottages.” Longtime residents weren’t happy when the America’s Cup defected, or when Bob Dylan went electric at the Folk Festival, or when Maya Lin designed a contemporary memorial to honor the heiress Doris Duke in the village green. Epstein Joslyn Architects Inc. A rendering of the proposed visitors center at the Breakers. Portable toilets are there now. And they’re not happy now that the local preservation society, in the name of progress, has proposed a visitors center — with wheelchairaccessible bathrooms and prepared food — on the grounds of the most visited mansion, the Breakers, where the Vanderbilt family’s carved oak dining room table could seat 34 and at least one daughter changed her outfit up to seven times a day. Letters to editors are pouring in on both sides of the debate. Sleepy town commissions are suddenly heated forums. Friends are not talking to friends. In a letter in a Newport weekly in August, Gloria Vanderbilt, the fashion designer whose grandfather Cornelius Vanderbilt II built the Breakers in the 1890s, made her case against the project, hailing the house as “a reminder of a lost world.” “People come to experience the fantasy, the wonder and beauty of that world,” she continued. “If the first thing they see upon entering the gates of this magical kingdom is a new building selling plastic shrink-wrapped sandwiches, it will forever change their enjoyment of the visit.” In a column in May in The Providence Journal, David Brussat took an opposing view, praising the proposed building, to be tucked into a grove of trees, as “sort of like a Gilded Age conservatory or greenhouse that would fit like a glove into its context.” Last month, the Newport Historic District Commission voted 4 to 3 against the society’s proposal. The Preservation Society of Newport, a nonprofit organization that owns and operates the city’s mansions, on Monday appealed the decision to the zoning board. A ruling is not expected until later this fall. The strain on social relations is evident to Lisette Prince, a former trustee of the Preservation Society, who opposes the center and says that Trudy Coxe, the society’s chief executive, isn’t speaking to her anymore. (Ms. Coxe said, “That’s simply not correct at all.”) Helen Winslow — widow of John Winslow, once president of the society — said she felt compelled to publish a letter in The Newport Daily News opposing the project. Ms. Winslow, who is 94, said Donald O. Ross, the society’s chairman, subsequently upbraided her as she was having Sunday lunch at her beach club, after which she received a written apology from Mr. Ross’s wife, Susan. (Asked about this, Mr. Ross said, “I just don’t think it’s relevant.”) Perhaps only in a town where a 70-room Italian Renaissance-style palazzo like the Breakers is called a “summer cottage” could a fight like this occur over a 3,650-square-foot glass pavilion. Part of the debate focuses on whether the food service at the center should be considered a restaurant, thus violating residential zoning laws. (The Preservation Society insists that the cafe would have no stove or dishwasher and therefore is unequivocally not a restaurant.) “Change is very hard for certain people,” Ms. Coxe said, “family members most particularly.” Indeed, various members of the Vanderbilt family have weighed in against the project, partly because they said they have felt excluded from the decision. Even after the Breakers opened for visits in 1948, and it was sold to the society in 1972, Vanderbilts continued to live on the third floor; two members of the family still do. “The Breakers is one of the most important buildings in the Northeast, if not the East Coast,” said one of them, Gladys V. Szapary, who added that her great-grandfather Cornelius “clearly wanted this landscape to stay free of buildings.” Ms. Szapary and others say they do not dispute the need for an improved tourist experience. “No one cares about the visitors at the Breakers more than I do,” she insisted. They’re even accepting of the design of the proposed pavilion. It should simply be placed elsewhere, they say, like the parking lot across the street, or at the end of Newport Bridge, where people could stop to buy tickets to the Breakers and other mansions on their way into town. “The building looks like Tavern on the Green to me,” said Ms. Prince, who has long family ties to Newport. “It’s fine, but not there. It doesn’t fit.” They also say that tourists want to see all 13 acres of the Breakers as they were originally, and that the house was designated a National Historic Landmark partly because of the landscaped grounds, designed by Ernest Bowditch, a student of Central Park’s designer Frederick Law Olmsted. “All of the property was considered to be what was significant,” said Robert Beaver, chairman of the Bellevue Ochre Point Neighborhood Association, who has lived in Newport for nearly half a century. He and his wife, longtime donors to the Preservation Society, will not be giving this year. “A modern intruder should not be placed into the grounds of the Breakers,” Mr. Beaver said. For its part, the society says that the visitor center will provide a more comfortable welcome and a more comprehensive introduction to Newport’s other 10 mansions. “We need a very high standard here in Newport,” said Mr. Ross, the society chairman. “Our visitors deserve it.” Supporters of the pavilion say it should be on the premises, as such centers typically are. “The Liberty Bell, the White House, Mount Vernon — all of these places have facilities at the gate,” said Mark Brodeur, the director of tourism at the Rhode Island Economic Development Corporation. “If we’re going to teach the Gilded Age to the consumer, we have to start doing that from the get-go.” The center would be built to the left of the Breakers entrance, where a tent and portable toilets have been for the last decade. These temporary accommodations are run down, the society says, and inadequate for the Breakers’ 400,000 annual visitors. “I want these people to enjoy themselves and want them to have an experience they will never forget,” Ms. Coxe said. “I don’t know of any museum that makes you go to the bathroom in a port-o-john or makes you buy a ticket out of a tent.”