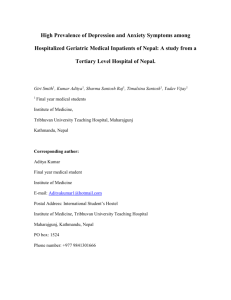

High Prevalence of Depression and Anxiety Symptoms among

advertisement

High Prevalence of Depression and Anxiety Symptoms among Hospitalized Geriatric Medical Inpatients of Nepal: A study from a Tertiary Level Hospital of Nepal. Giri Smith1, Kumar Aditya1, Sharma Santosh Raj1, Timalsina Santosh1, Yadav Vijay1 1 Final year medical students Institute of Medicine, Tribhuvan University Teaching Hospital, Maharajgunj Kathmandu, Nepal Corresponding author: Aditya Kumar Final year medical student Institute of Medicine E-mail: Adityakumar1@hotmail.com Postal Address: International Student’s Hostel Institute of Medicine, Tribhuvan University Teaching Hospital Maharajgunj, Kathmandu, Nepal PO box: 1524 Phone number: +977 9841301666 ABSTRACT Introduction: Depression and Anxiety are widely prevalent in the geriatric population and the prevalence is higher in those suffering from any kind of medical illness. Although the prevalence of anxiety and depression among elderly medical patients has been evaluated in a few studies from developed countries like Europe and Americas, data from a developing country like Nepal is lacking. The main aim of our study was to estimate the burden of these psychiatric morbidities in our setting. Materials and methods: A cross sectional analytical study was done where 42 Geriatric inpatients admitted to the Department of Internal Medicine of Tribhuvan University Teaching Hospital during the period of April 1st to May 20th 2009 were studied for the prevalence of Depression and Anxiety using the Nepalese version of Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) and Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) respectively. 23 healthy geriatric community dwellers from a senior citizen centre in Kathmandu were taken as the control group. Data was analyzed using SPSS 14.0. Results: Significant anxiety symptoms were present in 76.1% (N=32) of the hospitalized geriatric patients and significant depressive symptoms in 57.1% (n=24) as compared to 21.7% (n=5) and 17.3% (n=4) of healthy community dwellers respectively. Between the hospitalized geriatric medical inpatients and the elderly healthy community dwellers, there was statistically significant differences in anxiety scores (F=26.06, p<0.01) and depression scores (F=22.97, p<0.01) as measured by one way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA). Conclusion: There is very high prevalence of depression and anxiety among hospitalized geriatric medical inpatients as compared to the healthy community dwellers in Nepal. Presence of these psychiatric morbidities can further exacerbate the physical illness slowing down recovery and adversely affecting a wide range of outcomes. Such a high amount of psychiatric morbidity in this population needs to be addressed by appropriate mental health interventions. INTRODUCTION Depression is one of the most common conditions associated with suicide in adults1and is also a widely under-recognized and undertreated medical illness. Studies show that many adults who die by suicide (up to 75 percent) visited a physician within a month before death.2 All these facts highlight the urgency that must be undertaken in the detection and treatment of depression among the geriatric age groups. Estimates of major depression in the geriartric population living in the community range from less than 1 percent to about 5 percent, but rises to 13.5 percent in those who require healthcare at home and to 11.5 percent in hospitalized patients3. Health professionals may mistakenly think that persistent depression is a normal response to other serious illnesses and the social and financial hardships that come along with ageing4,5.This contributes to low rates of diagnosis and treatment in the geriatric population. Controversy still remains as to the exact prevalence of anxiety symptoms in the geriatric population: both clinical and community samples have shown that anxiety is fairly common in this age group6,7. Although late-life anxiety has been the focus of far less research than depression, there is good evidence that both anxiety and depression (alone and in combination with physical illness) are linked to poor physical and psychosocial functioning8. Evidence shows that mental and physical health affect each other in reciprocal ways to have deleterious effects on a range of outcomes9. This includes decreased satisfaction with life, increased drug dependency, and less favorable outcomes of common health conditions9-12. This has shown that mental health interventions are very much necessary in physical health settings in this population group13. However these interventions will not be possible without gaining adequate knowledge about the prevalence, course and significance of these problems. Although the prevalence of anxiety and depression amongst geriatric medical patients has been evaluated in a few studies from developed countries in Europe and the Americas, data from a developing country like Nepal is lacking. Because of a different sociocultural scenario, poor health awareness and relatively underdeveloped psychiatric medical services, the prevalence of these psychiatric morbidities could be much more in our setting. MATERIALS AND METHODS This is a cross sectional analytical study taking geriatric medical inpatients admitted to the Internal Medicine Department of Tribhuvan University Teaching Hospital. Apparently healthy geriatric population from an elderly home will be taken as the control group. All the geriatric inpatients admitted to the Department of Internal Medicine of Tribhuvan University Teaching Hospital during the period from April 1st to May 20th 2009 were included in the study. Criteria for inclusion were: Age ≥ 65yrs Suffering from any Medical Illness (Acute or Chronic) Having good Cognitive Function (sumscore 10-12 on Mini Mental State Examination). Exclusion criteria were: Terminally ill patients Severe life events in the past 6 months (eg. Loss of a spouse or children) Known Psychiatric Disorders including Post Traumatic Stress Disorder Note: The last two would confound results and lead to high rates of depression and anxiety not necessarily attributed to the current medical illness. 23 Healthy geriatric individuals were recruited from one senior citizen center (Nisahaya Sewa Sadan) in Kathmandu as the control group. The criteria for inclusion and exclusion were the same as the inpatients except that: a) They should not be suffering from any acute or chronic medical illness b) They should not be under any psychoactive drugs. Out of 40 eligible candidates, only 23 were selected by simple random sampling technique using a computer generated table of random numbers. H0 (Null hypothesis): There is no difference in the prevalence of depression and anxiety among geriatric hospitalized medical inpatients as compared to geriatric healthy community dwellers. H1 (Alternative hypothesis): There is a significant difference between the prevalence of depression and anxiety among geriatric hospitalized medical inpatients as compared to geriatric healthy community dwellers. The prevalence of population of depression and anxiety symptoms among both the subsets of the population were studied using the Nepalese version of Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) and Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) respectively. Nepalese version of both these Inventories have been tested and validated in Nepalese population14,15 . Analysis of the Data was done using SPSS 14.0. Test of significance of the difference of prevalence of these psychoactive morbidities among the case and control group was done by using one way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) and the difference between the inventory scores among various clinical categories was done using appropriate significance tests. RESULTS Out of a total of 45 hospitalized geriatric inpatients admitted to the Department of Internal Medicine of Tribhuvan University Teaching Hospital during the study period, only 42 were eligible for the study. Similarly 23 healthy geriatric community dwellers were interviewed for the study as the control group. The mean age group for the geriatric inpatients was 69.1 with a standard deviation of 4.8. The mean number of illness was 2.5 (S.D=1.3). The mean duration of illness was 5.8 years with a standard deviation of 5.2 years. The mean anxiety score was 21 (S.D=12.9) and the mean depression score was 22.3 (S.D=14.4). 47% (n=20) in the patients from Kathmandu and 53% (n=22) in the patients from outside Kathmandu. Regarding the control population, the mean age of the patients was 69.4 years with a standard deviation of 4.3 years. The mean anxiety score was 6.8 (S.D=3.2) and the mean depression score was 7.6 (S.D=3.2). The difference between the mean age of the hospitalized patients and healthy controls was not statistically significant (p value= 0.853). There was no statistical difference in terms of gender distribution among the cases and the control group (p value=0.798) 56.1% (n=24) of the geriatric medical inpatients were having significant depressive symptoms as compared to only 17.3% (n=4) of healthy community dwellers. Similarly 76.1% (n=32) of geriatric medical inpatients were having significant anxiety symptoms as opposed to 21.7% (n=5) of the healthy community dwellers. There was no significant difference in relation to the gender in the anxiety score as tested by one way Analysis of Variance (F=0.69, p=0.41) and also for depression score (F=2.05, p=0.15). There was poor correlation between the age of the patient and anxiety score (Pearson correlation coefficient 0.42) and depression score (correlation coefficient 0.38). There was however a strong correlation between number of illness and anxiety score (Pearson correlation=0.78) and between number of illness and depression score (Pearson correlation=0.80). Also the duration of illness showed very strong correlation with the anxiety score (Pearson correlation=0.8) and depression score (Pearson correlation=0.79). The anxiety and depression scores were strongly correlated with Karl Pearson correlation coefficient calculated to be 0.91. Between the hospitalized geriatric medical inpatients and elderly healthy community dwellers, there were statistically significant differences in anxiety scores (F=26.06, p<0.01) and depression scores (F=22.97, p<0.01) as measured by one way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA). Figure 1: Age distribution of the study population 30 25 25 20 Number of 15 Individuals 14 Cases 12 Controls 10 5 5 5 4 0 65-69 yrs 70-74 75 & above Figure 2: Sex distribution of the study population 45 40 20 35 30 Number of 25 Individuals 20 female 22 12 15 10 11 5 0 cases controls male Table 1: Distribution of the hospitalized patients according to number of illness Number of illness Frequency Percent Cumulative percent Single 12 28.6 28.6 Two 12 28.6 57.1 Three 8 19.0 76.2 Four 6 14.3 90.5 Five or more 4 9.5 100 Table 2: Distribution of the hospitalised patients according to the number of illnesses Duration of illness Frequency Percentage Cumulative percentage ≤1 yr 8 19.0% 19% >1 yr-≤5yr 16 38.1% 57.1% >5yr-≤10yr 13 31.0% 88.1% >10yr 5 11.9% 100% Figure 3: BAI categories in our study population 25 20 20 18 15 Number of Individuals case 10 10 controls 8 4 5 4 1 0 0 Minimal (0-7) Mild (8-15) Moderate (1625) Severe (26-63) Figure 4: BDI categories in the study population 20 19 18 18 16 15 14 12 Number of 10 Individuals 8 Case Control 6 6 4 4 3 2 0 0 Moderate (1929) Severe (30-63) 0 Minimal (0-9) Mild (10-18) DISCUSSION Out of the 42 hospitalized geriatric medical inpatients, significant depressive symptoms were present 57.1% (n=24). This is consistent with the prevalence rate of 53% as suggested by Khatri et al in 2006 among geriatric patients randomly selected from psychiatry, medicine and general practice outpatient departments in a tertiary level hospital of Nepal16. Similar study by Burns et al in UK showed that depression was prevalent in 45% of geriatric admissions17. Addshead et al in 1992 showed that depression was prevalent in 31.9% of medical inpatients18. Significant anxiety symptoms were present in 76.1% (N=32). A prevalence of between 5% and 68% has been shown by many epidemiological studies7. Kvaal et al in 2000 showed that up to 41% and 47% of the female and male medical inpatients respectively were suffering from significant anxiety disorder. Also the anxiety symptoms were significantly higher in medical inpatients than in age and sex matched controls taken from healthy community dwellers7 Compared to data from other international studies, our study showed very high anxiety and depression rates. Such a high prevalence in our country could be attributed to poor health awareness and underdeveloped psychiatric medical services in the country as well as an inadequate social support provided by their family and the government. Another factor could be the financial hardship that accompanies medical illness as there is no social security as well as health insurance systems in the country. One additional factor here is that there is very little counseling practiced so that people are uniformed about their illness which makes them quite anxious as well as depressed. Such a high prevalence of these psychiatric morbidities as seen in our study could also be due to the fact that we used a screening tool for estimating the prevalence rather than a diagnostic tool (eg. an expert psychiatrist’s assessment). Hence for further verifying the prevalence of these psychiatric morbidities in such a population, studies using diagnostic methods are recommended. CONCLUSION There is a very high prevalence of depression and anxiety among hospitalized geriatric medical inpatients as compared to healthy community dwellers in Nepal. Presence of these psychiatric morbidities can further exacerbate the physical illness slowing down recovery and adversely affecting a wide range of outcomes. Such a high amount of psychiatric morbidity in this population needs to be addressed by appropriate mental health interventions. REFERENCES 1. Conwell Y, Brent D. Suicide and aging I: patterns of psychiatric diagnosis. International Psychogeriatrics. 1995;7(2):149-64. 2. Conwell Y. Suicide in later life: a review and recommendations for prevention. Suicide and Life Threatening Behavior. 2001;31(Suppl):32-47. 3. Depression Guideline Panel. Depression in primary care: volume 1. Detection and diagnosis. Clinical practice guideline, number 5. AHCPR Publication No. 93-0550. Rockville, MD: Agency for Health Care, Policy and Research, 1993. 4. Hybels CF and Blazer DG. Epidemiology of late-life mental disorders. Clinics in Geriatr Med .2003;19(4):663-96. 5. Lebowitz BD, Pearson JL, Schneider LS, Reynolds III CF, Alexopoulos GS, Bruce ML, Conwell Y, Katz IR, Meyers BS, Morrison MF, Mossey J, Niederehe G, Parmelee P. Diagnosis and treatment of depression in late life. Consensus statement update. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1997;278(14):1186-90. 6. Bryant C., Jackson H., Ames D. The prevalence of anxiety in older adults: methodological issues and a review of literature. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2008; 109:233-250. 7. Kvaal, K., Macijauskiene, J., Engedal, K. and Laake, E. High prevalence of anxiety symptoms in hospitalised geriatric patients. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2001;16:690–693. 8. Lenze, E. et al. The association of late-life depression and anxiety with physical disability: a review of the literature and prospectus for future research. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2001;9:113–135. 9. Bruce, M. Depression and disability in late life. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2001;9:102–112. 10. Kroenke, K., Jackson, J. and Chamberlin, J. Depressive and anxiety disorders in patients presenting with physical complaints: clinical predictors and outcome. American Journal of Medicine. 1997;103:339–347. 11. Shimoda, K. and Robinson, R. Effect of anxiety disorder on recovery from stroke. Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 1998;10:34–40. 12. Bryant C., Jackson H, Ames D. Depression and anxiety in medically unwell older aduslts: Prevalence and Short term Course. International Psychogeriatrics 2009;21((4): 754-763. 13. Lichtenberg, P. and MacNeill, S. Streamlining assessments and treatments for geriatric mental health in medical rehabilitation. Rehabilitation Psychology. 2003;48:56– 60. 14. Kohrt BA, Kunz RD, Koirala NR, Sharma VD, Nepal MK. Validation of a Nepali version of the Beck Depression Inventory. Nepalese J Psychiatry. 2002;2:123-130. 15. Kohrt BA, Kunz RD, Koirala NR, Sharma VD, Nepal MK. Validation of the Nepali version of Beck Anxiety Inventory. J Institute Med 2003;25:1-4 16. Khattri JB, Nepal MK. Study of depression among geriatric population in Nepal. Nepal Med Coll J. 2006 Dec;8(4):220-3 16. Burn WK, Davies KN, McKenzie FR, Brothwell JA, Wattis JP. The prevalence of psychiatric illness in acute geriatric admissions. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1993;8:171-4. 17. Adshead F, Day Cody D, Pitt B. BASDEC: a novel screening instrument for depression in elderly medical inpatients. Br Med J. 1992;305:397.