File

advertisement

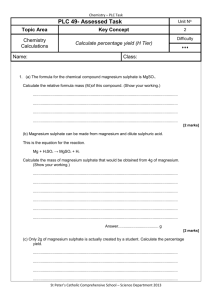

Carolyn Klempay KNH 413 Nutrient Information Medical Nutrition Therapy Nutrient Magnesium 1. What is the nutrient? Magnesium is a mineral that is found in the body and is presented naturally in foods. Magnesium works with other enzyme systems that collaborate to regulate bodily reactions including protein synthesis, muscle function, and blood pressure regulation. This nutrient assists in the process of glycolysis, contributes to the structural development of bone, helps the active transport of calcium and potassium, and contributes to normal heart rhythms. 2. What is the RDA/DRI for the nutrient? Magnesium intake is based on the Dietary Reference Intake (DRI) information that describes a general set of reference values used to assess the nutrition of healthy individuals. These standards for the Recommended Daily Allowance (RDA) for magnesium differ based on age and gender. A table which breaks down recommendations in a visual way is displayed below. Age Birth to 6 months 7–12 months 1–3 years 4–8 years 9–13 years 14–18 years 19–30 years 31–50 years 51+ years Male 30 mg* 75 mg* 80 mg 130 mg 240 mg 410 mg 400 mg 420 mg 420 mg Female 30 mg* 75 mg* 80 mg 130 mg 240 mg 360 mg 310 mg 320 mg 320 mg Pregnancy 400 mg 350 mg 360 mg Lactation 360 mg 310 mg 320 mg 3. How is the nutrient metabolized? On average, an adult body will contain about 25 grams of magnesium, the larger portion being present in the bones, and the remaining in the soft tissues. About 30%-40% of the dietary magnesium that is taken into the body is typically absorbed. The regulation of magnesium levels in the body is highly controlled by proper kidney functioning which allows excess mineral to be excreted in the urine or decreases excretion when magnesium reserves are low. Magnesium levels, although very difficult to gain an accurate and precise measurement of mineral status, can be measured through serum concentration evaluations. 4. What are food sources of the nutrient? This mineral is common in many plant and animal sources of food, as well as various beverages. Good sources of magnesium include green leafy vegetables such as spinach in addition to whole grains, nuts, seeds, and legumes. A general rule states that foods which are good sources of dietary fiber also tend to be good magnesium sources as well. Foods such as breakfast cereals may be fortified with magnesium and contrarily, heavily processed foods may be lower in magnesium due to the removal of nutrient-rich portions during the refining of certain grains. Water that is from the tap or bottled may possess magnesium, however, the amount varies greatly depending on water source and brand. Specific foods that are high in magnesium include almonds, spinach, cashews, peanuts, cereal, soymilk, black beans, edamame, peanut butter, whole wheat bread, avocado, brown rice, and plain low-fat yogurt. It is not required by the FDA to list the magnesium content of foods in the nutrition facts label unless the food has been fortified with the mineral. 5. What disease states alter the nutrients metabolism? Individuals with gastrointestinal diseases are at risk for magnesium depletion over time. These diseases can include Crohn’s disease, gluten-sensitive enteropathy (Celiac disease), or enteritis. Instances in which the small intestine, particularly the ileum, is bypassed can usually lead to loss of magnesium through malabsorption. Type 2 Diabetes is another disease state that can alter the metabolism of magnesium due to increased magnesium excretion. Because of increased glucose concentrations in the kidneys, urinary magnesium output is increased as well, creating a mineral imbalance. Alcoholism is a third disease state in which magnesium absorption and metabolism is highly affected. Poor nutritional intake and dietary magnesium consumption, chronic vomiting, diarrhea, and steatorrhea can lead to renal dysfunction and excessive magnesium excretion. Vitamin D deficiency, alcoholic ketoacidosis, and liver disease are all contributing factors to a decreased magnesium status in those who have alcohol dependence. Lastly, older adults, even without diagnosis of a particular disease state, have lower dietary intake of magnesium and higher risk for inadequate mineral metabolism. Absorption of magnesium in the gut decreases with age and chronic illness or additional medications taken by older adults create increased potential for disrupted magnesium metabolism. 6. What are the tests or procedures to assess the nutrient level in the body? Assessing the nutrient magnesium in the body is somewhat difficult because most of this mineral is housed inside cells or bone. Measuring the serum magnesium concentration is the most commonly used method of mineral assessment. Although serum magnesium has very little correlation to total bodily and specific tissue magnesium concentration, this method is most readily available for use. Additional testing procedures to evaluate magnesium concentration in the body include measuring concentrations of magnesium in erythrocytes, saliva, urine, blood, plasma, and serum magnesium through magnesium-loading or “tolerance” testing. Some researchers consider the tolerance test to be the most accurate method of magnesium concentration assessment. In this test, a parenteral infusion of a magnesium dosage is given and after, urinary magnesium is measured to assess excretory properties. Ultimately, a combination of clinical and laboratory assessments are needed to get the most accurate measurement of this mineral’s presence in the body. 7. What are the drug-nutrient interactions? Magnesium status has the potential to be affected when in combination with particular medications and it is important that those who take these medications speak with a physician about the possibility of medical concerns. Bisphosphatates used to treat osteoporosis may be altered in effectiveness due to magnesium-containing supplements. Separate magnesium supplements and bisphosphatate intake by at least two hours to prevent interactions. Antibiotics and diuretics should also be taken several hours after or before taking magnesium supplements due to the potential of interactions and increasing magnesium deficiency risks. Proton pump inhibitors, when taken consistently for long periods of time, also have the ability to cause hypomagnesemia. If this medication is necessary, regular measurements of magnesium status should be taken and monitored for substantial changes. 8. How is the nutrient measured? This nutrient is measured in grams or mmols in the body. Measurements are gained through evaluation of serum magnesium levels in saliva, urine, and blood plasma. Additionally, studying the results of concentrated magnesium intake, and excretory magnesium measurements can assist in the measurement of this nutrient. 9. What is the Upper Tolerable Limit? Tolerable upper limits for magnesium for infants, children, and adults apply only to magnesium supplementation, not to dietary consumption. A table to display these Upper Tolerable Limits is displayed below. Age Birth to 12 months 1–3 years 4–8 years 9–18 years 19+ years Male None established 65 mg 110 mg 350 mg 350 mg Female None established 65 mg 110 mg 350 mg 350 mg Pregnant 350 mg 350 mg Lactating 350 mg 350 mg 10. What are the physical signs of deficiency? Physical signs of a magnesium deficiency include loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting, fatigue, and weakness. These beginning signs can worsen as the deficiency increases and additional physical signs are numbness, tingling sensations, muscle contractions, muscle cramps, seizures, abnormal heart rhythms, coronary spasms, and changes in personality. Extremely severe cases in the deficiency of this mineral may result in low serum calcium and low serum potassium levels (hypocalcemia and hypokalemia respectively) due to the imbalance and disruption in mineral homeostasis. 11. What are the physical signs of toxicity? High magnesium levels due to excessive magnesium supplementation can result in physical signs of diarrhea, nausea, and abdominal cramping. It is quite unlikely that magnesium toxicity can result from dietary intake because of the kidney’s process of mineral regulation and excretion. Severe cases of magnesium toxicity, when serum concentrations exceed 1.74-2.61 mmol/L, will ultimately lead to hypotension, nausea, vomiting, facial flushing, urine retention, depression, and lethargy. These initial signs can worsen to muscle weakness, difficulty breathing, extreme hypotension, irregularities in heartbeat, and even cardiac arrest. Resources: NIH. (2013, November 4). Magnesium. — Health Professional Fact Sheet. Retrieved April 21, 2014, from http://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Magnesium-HealthProfessional/