Post-Operative Follow Up of Traumatic Blunt Aortic Injury Patients

advertisement

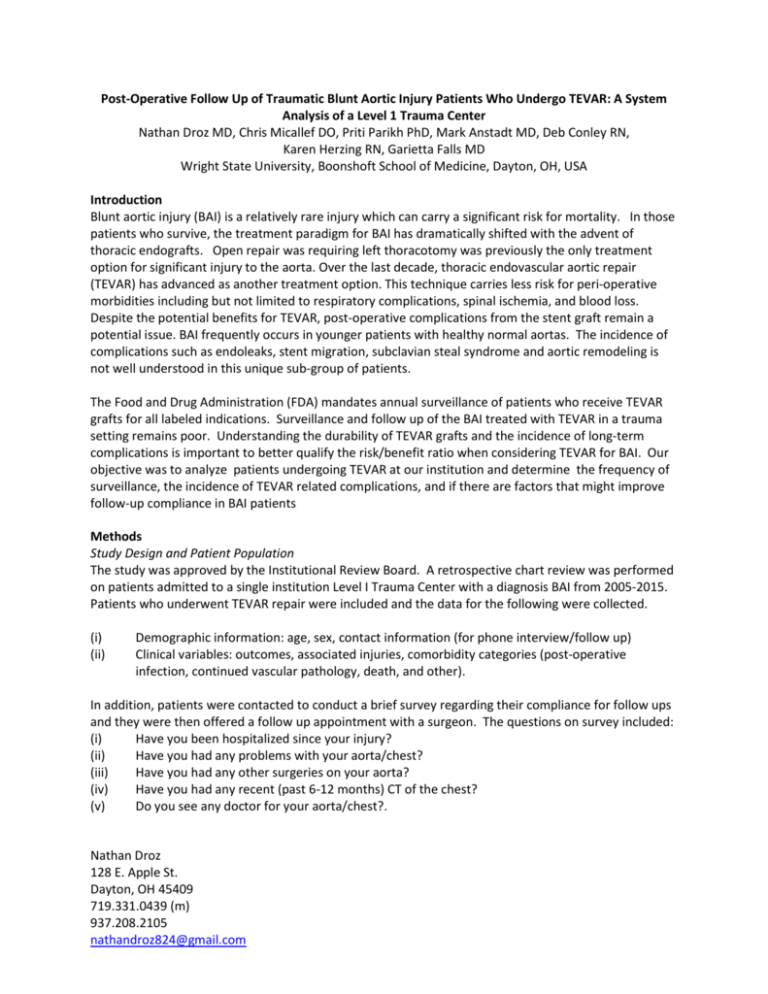

Post-Operative Follow Up of Traumatic Blunt Aortic Injury Patients Who Undergo TEVAR: A System Analysis of a Level 1 Trauma Center Nathan Droz MD, Chris Micallef DO, Priti Parikh PhD, Mark Anstadt MD, Deb Conley RN, Karen Herzing RN, Garietta Falls MD Wright State University, Boonshoft School of Medicine, Dayton, OH, USA Introduction Blunt aortic injury (BAI) is a relatively rare injury which can carry a significant risk for mortality. In those patients who survive, the treatment paradigm for BAI has dramatically shifted with the advent of thoracic endografts. Open repair was requiring left thoracotomy was previously the only treatment option for significant injury to the aorta. Over the last decade, thoracic endovascular aortic repair (TEVAR) has advanced as another treatment option. This technique carries less risk for peri-operative morbidities including but not limited to respiratory complications, spinal ischemia, and blood loss. Despite the potential benefits for TEVAR, post-operative complications from the stent graft remain a potential issue. BAI frequently occurs in younger patients with healthy normal aortas. The incidence of complications such as endoleaks, stent migration, subclavian steal syndrome and aortic remodeling is not well understood in this unique sub-group of patients. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) mandates annual surveillance of patients who receive TEVAR grafts for all labeled indications. Surveillance and follow up of the BAI treated with TEVAR in a trauma setting remains poor. Understanding the durability of TEVAR grafts and the incidence of long-term complications is important to better qualify the risk/benefit ratio when considering TEVAR for BAI. Our objective was to analyze patients undergoing TEVAR at our institution and determine the frequency of surveillance, the incidence of TEVAR related complications, and if there are factors that might improve follow-up compliance in BAI patients Methods Study Design and Patient Population The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board. A retrospective chart review was performed on patients admitted to a single institution Level I Trauma Center with a diagnosis BAI from 2005-2015. Patients who underwent TEVAR repair were included and the data for the following were collected. (i) (ii) Demographic information: age, sex, contact information (for phone interview/follow up) Clinical variables: outcomes, associated injuries, comorbidity categories (post-operative infection, continued vascular pathology, death, and other). In addition, patients were contacted to conduct a brief survey regarding their compliance for follow ups and they were then offered a follow up appointment with a surgeon. The questions on survey included: (i) Have you been hospitalized since your injury? (ii) Have you had any problems with your aorta/chest? (iii) Have you had any other surgeries on your aorta? (iv) Have you had any recent (past 6-12 months) CT of the chest? (v) Do you see any doctor for your aorta/chest?. Nathan Droz 128 E. Apple St. Dayton, OH 45409 719.331.0439 (m) 937.208.2105 nathandroz824@gmail.com Comorbidities For analysis of the data, specific diagnoses were assigned to broad comorbidity categories. Patients with more than one diagnosis within a comorbidity category were recorded as positive within that category, with no subcategorization. Thus, patients were classified with the following comorbidities if one or more of the following in each category were documented in the trauma patient’s medical record: (i) Post operative infection: pneumonia, empyema (ii) Continued vascular pathology: endoleak type I, pseudoaneurysm, arterial occlusion, bleeding, lymphocele (iii) Other: pleural effusion, hemothorax (iv) None Practice Type Data was further analyzed based on practice type. The Wright State University Department of Vascular Surgery and Miami Valley Heart and Lung Surgeons, a private Cardiothoracic Surgery practice were analyzed independently in regards to short and long term follow up. Short term follow up defined as one month or less and long term follow up defined as greater than three years. Data were then descriptively analyzed and reported. Results A total of 26 patients underwent TEVAR for treating BAI during the study period. The majority were male (69%) and mean ages was 47.67 (range was 22-80 years). Complication occurred in 13 patients (50% Table 1). rate was 52% (n=13). Complications were categorized post-operative infection, continued vascular pathology, other, or no complication. Three patients (12%) developed pneumonia, one (4.0%) a ventilator associated pneumonia (VAP) and one (4.0%) developed an empyema requiring operative intervention. Five patients (20%) had a vascular pathology following TEVAR. Three patients (12%) developed type I endoleaks documented by CT scan while still in house; one was repaired by median sternotomy and graft removal, one was repaired by left thoracotomy and the other was transferred to another tertiary center where endovascular repair, median sternotomy and debranching was required. One patient (4.0%) required a tube thoracostomy for hemothorax and three others (12%) required drainage of pleural effusions. Table 2 shows compliance for follow up in TEVAR patients for both university and private practice groups. Average follow up amongst both the groups was similar (28 months for the university practice and 24 months for the private practice). The data shows the short term follow up is higher in private practice patients (100%) than university group (75%). Long-term follow up between the two practice types is similar. Two (25%) of the university patients and 5 (27%) of the private practice patients were followed for longer than three years and had a CT scan during this follow up period. Reasons for longterm follow up failure were (i) discharge to rehab or long- term care facilities out of the region, (ii) have moved out of the state/region, (iii) felt well, (iv) lack of appropriate/most current contact information. Of the 26 patients identified, only 4 (15%) were able to be reached by telephone and only two (11%) of the private practice patients agreed to respond to our questionnaire. None of the patients who answered our call were patients who weren’t already being actively followed. Nathan Droz 128 E. Apple St. Dayton, OH 45409 719.331.0439 (m) 937.208.2105 nathandroz824@gmail.com Table 1. Complications from TEVAR Number of patients Notes Post Operative Infection 5 Continue vascular pathology 5 Other None 3 13 Pneumonia (3) VAP (1) Empyema (1) Type I Endoleak (3) all requiring open repair Pseudoaneurysm (1) Arterial occlusion (1) Hemothorax (1) Pleural effusion (3) n/a Table 2: Surveillance and Compliance for Follow up in TEVAR Patients Practice type University Total number of patients 8 (31%) Private practice 18 (69%) Total Average months of follow up Number of patients followed up within one month following the procedure (with CT scan) Number of patients with long term follow up >3yrs Number of patients answered the call Number of patients who participated in interview 28 6 (75%) 24 18 (100%) 24 24 (92%) 2 (25%) 2 (25%) 0 (0%) 5 (27%) 2 (11%) 2 (11%) 7 (27%) 4 (15%) 2 (7.5%) 26 (100%) Conclusion TEVAR has evolved to the preferred treatment for most patients suffering BAI. The results of this study suggest short- term follow up results are relatively favorable. However, follow up beyond one year is very limited. Two most obvious barriers to follow up is the proximity of the trauma center to patients’ residence and resources to contact patients to arrange surveillance. Many patients discharged to care facilities and outside our trauma center’s region had no follow beyond one month. Contact information was noticed as an essential to continued long-term follow up. This explained why the response rates to our telephone survey. No significant difference was demonstrated between practice types in regards to follow up. While CT analysis was not part of this study, continued follow up in this cohort is needed to rule out effects on aortic remodeling and other potential endograft complications. In conclusion, efforts to improve follow- up after TEVAR in BAI patients remains an important challenge to substantiate that this treatment carries the long-term benefits that open repair affords this unique patient population. Nathan Droz 128 E. Apple St. Dayton, OH 45409 719.331.0439 (m) 937.208.2105 nathandroz824@gmail.com