Source: El Haj Ahmed, M. (2009) Lexical, Cultural, and Grammatical

advertisement

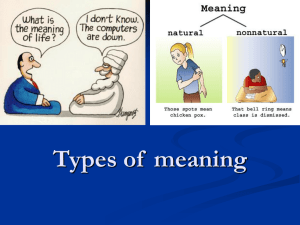

Dear students, Below is a discussion of the two concepts of denotation and connotation. Source: El Haj Ahmed, M. (2009) Lexical, Cultural, and Grammatical Translation Problems Encountered By Senior Palestinian EFL Learners at the Islamic University of Gaza, Palestine, Unpublished PhD Thesis, University of Salford, United Kingdom. 3.2.1. Denotation Lexical items have both denotative and connotative meanings. The denotative meaning, also known as the cognitive, propositional, conceptual or literal meaning, is “that kind of meaning which is fully supported by ordinary semantic conventions” (Dickins et al, 2002: 52). For example, the denotative meaning of the word ‘window’ refers to a particular kind of aperture in a wall or roof. It would be inaccurate to use ‘window’ to refer to other things than the particular references of the relevant sense of the word. Dictionaries seek to define meaning. However, dictionaries have their own problems. One of these is that “they impose, by abstraction and crystallization of one or more core senses, a rigidity of meaning that words do not often show in reality, and partly because, once words are put into a context, their denotative meanings become more flexible” (ibid: 52). These two reasons - the rigidity of meaning and the flexibility of words in contexts - make it difficult for the translator to determine the exact denotative meaning in any text including the most soberly informative texts. Intralingually, English shows some forms of semantic equivalence including full synonymy. For example, ‘my mother’s father’ and ‘my maternal grandfather’ are synonyms of one another. In other words, in every specific instance of use, ‘my mother’s father’ and ‘my maternal grandfather’ include and exclude exactly the same referents (Dickins et al, 2002: 53). However, full synonymy is exceptional, both intralingually and interlingually. In his/her attempt to find the closest equivalent to translate the denotative meaning of a source language item, the translator usually faces difficulty in finding a full target language synonym. An example which illustrates the difficulty the translator may face in finding an appropriate equivalent is the English term ‘uncle’ as compared to the 1 Arabic terms خالand عم. In English the term ‘uncle’ has a greater range of meanings than the Arabic terms خالand عم, as ‘uncle’ refers both to a father’s brother and mother’s brother. The relationship between ‘uncle’ and خالand between ‘uncle’ and عم is known as hyperonymy and hyponymy. According to Dickins et al, hyperonymy or superordination refers to an expression with a wider, less specific, range of denotative meaning. Hyponymy on the other hand refers to an expression with a narrow, more specific range of denotative meaning. Therefore خالor عمare both hyponyms of the English term ‘uncle’ (ibid: 55). Translating by a hyponym implies that the target language expression has a narrower and a more specific denotative meaning than the source language word. Dickins et al (2002: 56) call translation which involves the use of TT hyponym particularizing translation or particularization. In translating from English to Arabic, the target word خالis more specific than the source word ‘uncle’, adding the particulars not present in the source language expression. Another example which shows lexical differences between English and Arabic and may therefore create lexical translation problems is the lexical item ‘cousin’. In English ‘cousin’ can have eight different Arabic equivalents: 1. Cousin: ابن العم ‘the son of the father’s brother’ 2. Cousin: ابنة العم ‘the daughter of the father’s brother’ 3. Cousin: ابن العمة ‘the son of the father’s sister’ 4. Cousin: ابنة العمة ‘the daughter of the father’s sister’ 5. Cousin: ‘ ابن الخالthe son of the mother’s brother’ 6. Cousin: ابنة الخال ‘the daughter of the mother’s brother’ 7. Cousin: ابن الخالة ‘the son of the mother’s sister’ 8. Cousin: ‘ ابنة الخالةthe daughter of the mother’s sister’ All of the above eight Arabic terms are hyponyms of English ‘cousin’. The previous discussion has shown that there are semantic differences between English and Arabic that the translator should be familiar with. The translator should look for the appropriate target language hyperonym or hyponym when there is no full target language synonym for a certain language expression. 2 3.2.2. Connotation Unlike denotative meaning connotative meaning is described as “the communicative value an expression has by virtue of what it refers to, over and above its purely conceptual content” (Leech, 1974: 14). As Leech states, the word ‘woman’ is defined conceptually by three properties ‘human’, ‘female’, ‘adult’. In addition, the word includes other psychological and social properties such as ‘gregarious’, ‘subject to maternal instinct’. Leech maintains that ‘woman’ has the putative properties of being frail, prone to tears, and emotional. He (ibid: 14) distinguishes between connotative meaning and conceptual (denotative) meaning in the following ways: 1. Connotative meanings are associated with the real world experience one associates with an expression when one uses or hears it. Therefore, the boundary between connotative and conceptual meaning is coincident with the boundary between language and the real world. 2. Connotations are relatively unstable; they vary considerably according to culture, historical period, and the experience of the individual. Leech believes that all speakers of a particular language share the same conceptual (denotative) framework just as they share the same syntax. In Leech’s view, the overall conceptual framework is common to all languages and is a universal property of the human mind. 3. Connotative meaning is indeterminate and open-ended in the same way as our knowledge and beliefs about the universe are open-ended. In other words any characteristic of the referent identified subjectively or objectively, may contribute to the connotative meaning of the expression which denotes it. In contrast the conceptual meaning of a word or sentence can be codified in terms of a limited set of symbols, and the semantic representation of a sentence can be specified by means of a finite number of rules. Expressive meaning, as Baker (1992) calls it, refers to the speaker’s feelings or attitude rather than to what words or utterances refer to. In her opinion the two expressions ‘do not complain’ and ‘do not whinge’ have the same denotative meaning, but they differ in their connotative meaning. Unlike, ‘complain’, ‘whinge’ suggests that the speaker finds the action annoying (ibid: 13). 3 Based on Leech’s classification of meaning (1974: 26), Dickins et al (2002: 66-74) distinguish five major types of connotative meanings, as follows: 1. Attitudinal meaning: the expression does not merely denote the referent in a neutral way, but also hints at some attitude to it. For instance, ‘the police’, ‘the filth’ and ‘the boys in blue’ have the same denotative meaning. However, the expressions have different connotative meanings. ‘The police’ is a neutral expression, ‘the filth’ has pejorative overtones while ‘the boys in blue’ has affectionate ones. In the following example, the translator has used the term ‘lady’ rather than ‘woman’ since ‘lady’ has overtones of respect. يا أنثاي من بين ماليين النساء.....آه يا بيروت Ah Beirut….my lady amongst millions of women. 2. Associative meaning may consist of expectations that are rightly or wrongly associated with the referent of the expression. For example, the term ‘Crusade’ has strongly positive associations in English, whereas its Arabic equivalent حملة صليبيةhas negative associations, since the word is associated with the Crusades to Palestine in the Middle Ages. Conversely, the term جهادin Arabic has positive associations, since the word is associated with one of the five pillars of Islam, and those who are killed in the cause of Allah are rewarded with heaven on the Day of Judgement. On the contrary, the term جهادhas negative associations in the West, since the word is connected with international extremist organizations, especially after the September 11 attacks. 3. Affective meaning is related to the emotive effect worked on the addressee by the choice of expression. For instance, the two expressions ‘silence please’, and ‘shut up’, or الرجاء الصمتand أسكتin Arabic share the same denotative meaning of ‘be quiet’. However, the speaker’s attitude to the listener produces a different affective impact, with the first utterance producing a polite effect and the second one producing an impolite one. Therefore, the translator should choose a suitable lexical item that produces the same effect on the TL reader as that intended by the author of the original text on the SL reader. 4. Allusive meaning occurs when an expression evokes an associated saying or quotation in such a way that the meaning of that saying or quotation becomes part of 4 the overall meaning of the expression. For example, the oath االلتزام التام باإلخالص و الثقة . والسمع والطاعة في العسر و اليسر والمنشط و المكره,which members of the Muslim Brotherhood swore to their leader, Hassan Al Banna, alludes to the Quranic verses: إن إن مع العسر يسرا.( مع العسر يسراChapter: 94, Verses 5 and 6). 5. Reflected meaning is the meaning given to the expression over and above the denotative meaning which it has in that context by the fact that it also calls to mind another meaning of the same word or phrase. For example, the word ‘rat’ in ‘John was a rat’ has two meanings: the first denotative meaning is someone who deserts his friends, and the second connotative reflected meaning is the animal ‘rat’. In Arabic to call someone حمارmeans denotatively ‘stupid’. The word حمارalso refers to the animal ‘donkey’, which in this context provides a connotative reflected meaning*. Connotative meanings may differ from one place to another. Larson (1998) states that connotative meanings of lexical items differ from one culture to another, since the people of a given culture look at things from their own perspective. Many words which look like they are equivalent are not; they have special connotations (ibid, 149). For example, the lexical item بومةand the English word ‘owl’ have the same denotative meaning. As mentioned in (Section 1.1), both of them refer to the same class of bird. However, the two words have different connotative meanings. In Arabic the word بومةhas many negative connotations and is always seen as a symbol of bad luck, while in English, ‘owl’ has positive and favourable associations. To translate the English expressions: ‘He is as wise as an owl’ or ‘He is a wise old owl.’ into Arabic as هو حكيم كالبومةwould be unacceptable because of its negative connotations in Arabic. The English expressions are rendered into Arabic as ‘ هو حكيمHe is wise’. Problems in translation may arise when the translator does not take into account the different connotations of lexical items in the source and target language. Therefore, the translator may need to explain the connotative meaning of the lexical item in the form of a footnote or a definition within the text in order for the target language reader to understand the favourable or unfavourable connotations of the source language item. Connotative meanings may vary from one text type to another. For example, literary and religious texts make significant use of connotative meaning, as universality of terms used in these texts are not the norm. On the other hand, the terms used in scientific and technical texts are typically universal and thus entail one-to-one correspondence. According to Newmark (1981: 132) if the emphasis of the text is on information, clarity, simplicity and orderly arrangements are the qualities required for 5 conveying the information and achieving a similar effect on the target language reader as the source language author produced on the original reader. However, if the text attempts to persuade or direct the reader, the affective function is likely to dominate the informative function. Finally, if there is a nuance of persuasion, encouragement, scandal, optimism, pessimism, or determent, the reader is likely to react more strongly to it than to the information the text relates to. Newmark concludes that “the essential element that must be translated is the affective/persuasive, which takes precedence over the informative. It is the peculiar flavour, which in speech is the tone, not the words, which has to be conveyed” (ibid: 132-3). In order to convey the source language message to the target reader the translator should have a good knowledge of text types. This knowledge will enable the translator to choose the most appropriate equivalent in terms of denotative and connotative meaning in the target language. 6