Ch 4. Lambeth, Forest Hill and Ewhurst

advertisement

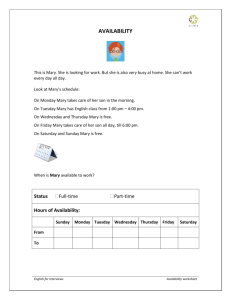

4. Lambeth, Forest Hill and Ewhurst a. James (4) [1797-1865] & Mary Ann In 1821, James Braby (4) married Mary Ann Churchman at Rudgwick. Born in 1799, she was the daughter of the late John Churchman and Ann (née Ireland) of Berrylands (now Bury St Austen’s) Rudgwick, and from 1791, on reaching his majority (after the death of his father in 1789), of Maybanks, Ewhurst, Surrey (see below). Mary Ann, who had been born and brought up at Maybanks, unfortunately died in 1828, perhaps in childbirth, only 29 years old, after just seven years of marriage. James had, though, secured an eventual inheritance in the shape of Maybanks for his only son James (5) born in Lambeth in 1826. James had two older sisters. Mary Ellen born 1823 survived to the age of 14, whilst Maria Ann born 1824 died in infancy at 6 months. Their children were, in order: 1. Mary Ellen, 1823-1838 2. Maria Ann, 1824-1824 3. James, 1826-1907 James and Mary Ann were living in Cornwall Road, Lambeth (probably in one of his father’s properties in that road) when Mary Ellen, Maria Ann, then James (5), were baptised. Mary Ellen died in Kentish Town in 1838. It is possible that the girl was with her grandparents who lived in Kentish Town, nearing retirement, or had James also moved there? This must have been a great loss for James to bear ten years after the death of his wife. James Braby’s machine for weighing coals off the back of a wagon, 1831. There must have been many short measures before this! After his wife’s early death James did not marry again, instead throwing himself into the business, with diversification. In 1831, James (4), aged 34, now in partnership with his father, and brother John, received much credit for his first recorded invention, a machine for weighing coals off the back of a wagon – enabling customers to see they had a fair measure. It won a premium of £20 from the Society of Owners of Coal Craft, and a Society of Arts Medal. In 1837, a patent was awarded for his improvements in construction of carriages, cabs and omnibuses. CHURCHMAN V BRABY CHURCHMAN V IRELAND THE HIGH COURT OF CHANCERY Churchman v Braby came before the High Court of Chancery in London in 1830, after the death of Mary Ann Braby in 1828, and in the same year as John Braby married Maria Churchman. The plaintiffs were John Churchman and another. John was the eldest of Mary Ann’s siblings, who lived at Maybanks. William Churchman, his brother, of Loxwood Place, was the other plaintiff. The defendants were: James Braby (4), James Braby (5) and Mary Ellen Braby (his two living children) John & Maria Braby, Ann Churchman, nee Ireland (Mary Ann and Maria’s widowed mother), Edward Churchman, Caroline Child, nee Churchman, Frederick Churchman, Eliza Allberry, nee Churchman (Mary Ann and Maria’s other siblings). James Braby (4) was appointed guardian of his two children who were ‘infants’, under age 21. The Bill of Complaint by the plaintiffs is not listed at National Archives, and may be lost, or it may be as below. The Answer of James Braby (5), and of Mary Ellen Braby infants, by their Guardian [i.e., James Braby (4), their father] two of the Defendants to the Bill of Complaint of John Churchman and William Churchman Complainants. Mary Ann Braby, mentioned in the said Bill, had died March 1828, leaving James Braby, mentioned as a Defendant thereto, her husband, and these defendants her only children. And these defendants say they are infants under the age of 21. “They claim they’ve been done wrong to”. It seems likely that the Brabys were asking to be considered as defendant/creditors in the 1829 Churchman v Ireland case laid out below, in which Mary Ann would have been a defendant had she lived. Churchman v Ireland had already come before the High Court of Chancery in London in 1829. This case followed on from the death and disputed Will of Thomas Ireland, Gent, of Garlands in Rudgwick. Thomas Ireland was an uncle of Mary Ann Braby. He was her mother’s brother. The case was cited in numerous legal books in subsequent years. The plaintiffs are the same as in the Braby case. The Bill of Complaint prayed at court, among other things, in respect of the field acquired after his grandfather made his will, that the heir [Thomas his grandson], who was one of the legatees, “might be put to his election” (see below). In the Answer, The defendants believed it to be true that Thomas Ireland entered into an agreement for the purchase of the tithes of his estate at Rudgwick in Dec 1820. In 1824, having made his Will in May 1820, Thomas Ireland purchased a close or field for £220. He died July 1827 without having altered or revoked this Will, in which he left his estate in trust to three trustees to support his eldest legitimate son John, subject to paying certain sums into the trust so that in the event of John’s death, one third would be paid to John’s children, two thirds to other legatees. However, Thomas’s grandson, also called Thomas Ireland, became the heir. John Ireland predeceased his father. Thomas’s illegitimate eldest son, John Harbroe Ireland and his nephew William Stanford declined or renounced the trusts and the estates thereby devised to them in the Will (they considered themselves disinherited). However, the defendants proved their case in the proper ecclesiastical courts. The defendants were, Elizabeth (nee Harbroe), Thomas Ireland’s wife; his deceased son John’s eldest son & heir Thomas; John’s siblings: John Harbroe Ireland, Sarah Butcher (wife of James), William Ireland, Ann Jarrett (wife of James), Mary Miles (wife of Henry); James, Owen and Caroline Ireland (infant children of John Ireland, deceased); Elizabeth, Mary, Philip, Catherine, Ann and Sarah Butcher (infant children of Sarah and James Butcher). James Limbert of Godalming was appointed guardian of the infants (all under age 21). Lawyers for the heir had appealed against an election, so as not to disinherit him, without any such express or necessary condition in the Will. An appeal was therefore made for the heir, that: ‘All my estate which I shall die possessed of’ means ‘all that is mine and shall continue to be mine until my decease’. I think the argument is that what was acquired after the Will was equally likely to be in the mind of the testator to pass on at his death as that which he had when writing the Will. Lawyers for the contradictory side argued: “to raise a case of election it is not necessary that the implication be unavoidable; it is enough that it be highly probable”. That the whole mass of the Ireland estate was to be put in trust for later distribution, place the intention beyond doubt. The Decision: the vice-chancellor of the court decreed that Thomas, the heir, was bound to elect (choose one or the other of two courses of action). The case then went before the Lord Chancellor who decided that “All my estate which I shall die possessed of” [in the Will] means “all my estates which being now mine, shall be mine till my decease” meaning “all that estate on which my Will can operate”. A testator must make clear in his Will what he is passing to his heirs. Only that which he states in the Will is to be passed to an heir. This Will therefore raised a case of implied condition, and the heir was bound to elect. The judgment of the vice Chancellor had to be affirmed, but as a precedent case made it doubtful, the Lord Chancellor declared “I shall affirm the present case without costs”. However, The London Law Magazine said, “[the judgment] met with anything but general acquiescence”. London Gazette, 1835: “by decree of the High Court of Chancery, in the cause of Churchman v Ireland, parish of Rudgwick, the creditors [defendants in the case] of Thomas Ireland who died in July 1827, were required to come to court to prove the debts owed them or in default they will be excluded from benefit.” b. James Braby & Son After their father’s death in 1846, James and John continued in the family business together. By the early 1850s, however, John (see below) had dropped out of the wheelwright business, in favour of James (5) – the firm now called James Braby & Son. The Braby family was very active and riding a wave of economic growth in the 1850s. In the 1851 P O Directory (the year of the Great Exhibition) “James Braby, carriage builder, contractor and wheelwright” is still at 22 Duke St. In 1856 the Post Office now lists “James Braby & Son, wheelwrights, carriage builders & smiths, patentees for improvements in carriages, 18 Duke street, Stamford street; Borough Haymarket [Southwark]; & 32 Bridgehouse place, Newington causeway” [also Southwark]. Presumably the works is at No 18 next door to the house. In the same London directory are John (slate merchant), Charles (hay and straw salesman), and Edward (a vet), all sons of James & Hannah. In addition, John’s son, Frederick was already a zinc merchant, after having learnt his business skills (see below) with his father and uncle. James Braby & Son flourished and diversified, with opportunities in the steam engine market, and railway rolling stock – Janet Balchin (Ewhurst Historical Society) records that they were contractors to the Government Ordnance Department. They exhibited at the 1851 Great Exhibition, at Crystal Palace, “a new application of springs to a caravan, or [coal] wagon, in which the perch bolt is placed behind the centre of the axletree, to allow a higher fore wheel, and give a greater amount of lock, and a machine for weighing coals, attached to the hind part of the caravan or wagon”, and, secondly, a “machine for weighing coals, attached to the hind part of the caravan or wagon” This appears to be the same or an improved version as he had made in 1831, followed in 1852 by a patent for “improvements in sawing machinery”. In 1854, new army ambulances were developed, which would have been horse drawn wagons, perhaps using the spring device above. In 1856, another improved sawing machine was brought out. James (4)’s last development in conjunction with his son was in 1858 (he was 60 by this time), “improvement to wheeled carriages propelled by steam, horses or other power with an apparatus for retarding the same”, possibly what we might call a brake (London Gazette). Curiously, there is no sign of James (4) in either the 1841 or 1851 censuses – a single widower is not easy to track down if no other person in the household is known for certain, and his son James (5) is also not to be found in 1841 – same address, missed in the count? But in the 1848 Post Office Directory, James (4) was living at Cranmer Place on Waterloo Road, round the corner from the works, his brother John nearby at 23 Modern perspective on the junction of Upper Stamford St. whilst their widowed mother at 59 Waterloo Road and Stamford Street. Camden Villa across town. James (4) married Emma Glover, 13 Feb 1857 at St Pancras Church. Both Braby’s are carriage builders. Above,Stanstead Lane, Forest Hill was still fairly rural when this 1:2500 O S map was made in 1895, showing the proximity of Stanstead Lodge (James (4)) and Stanstead Villa (James (5)) who lived there in the 1850s and 60s. Stansteadpark Nurseries were the business of noted horticulturalists Messrs Downie, Laird, and Laing. Below, the same area on the tithe map of 1843. the colouring has been added to show land use. It shows that there was a house where Stanstead Lodge was built. Steve Grindley, a local historian, believes it to have been built in the 1840s. The façade in the photo on the next page is later, possibly after Braby’s time. By 1858 (Melville’s Directory), James (4) had moved to Stanstead Lodge, a large house at Forest Hill in Lewisham. The white painted grade 2 Listed and recently restored house is still standing and used by a charity as a Seniors Club, in the lane now called Stanstead Road. Stanstead Lodge was the only house on Stanstead Lane in 1843. The railway had made Lambeth accessible from here by the 1850s, and the hill became an unpolluted refuge for the gentry. His son James (5) was virtually next door at Stanstead Villa, also in Stanstead Lane, and his nephew Frederick close by (Sydenham). Stanstead Lodge, Stanstead Road, Lewisham He had at the same time taken possession of Maybanks from the Churchmans, probably in 1857 on the death of John his late wife’s eldest brother in that year (more details, 4c), and was in residence there in 1861. Stanstead Lodge was his town house (1862 Kelly’s Directory), still useful when he needed to be in town or near his son’s family. By 1863, Stanstead Lodge was leased out. As the photo above shows it was a rather flamboyant house, though may well not have been white when first built. 1861 census James Braby (4), alone at Maybanks in his 400 acres, which also included land in Rudgwick In 1861, James lived at Maybanks, a widower, “landowner and occupier of 400 acres, employing 9 men and 4 boys”, looked after by a housekeeper, and intriguingly had a pupil apprentice aged 19 living with him. Perhaps James was more interested in passing on his wheelwright skills than in farming. Like his brother John he was part of Rudgwick’s landowning community as well as living in proximity at Maybanks. His interest in farming is illustrated by his attendance at the 1863 Christmas Horsham Cattle Show annual dinner at which he sat through interminable political speeches by the local MPs. Then, there is this curious piece from the Derby Mercury, May 25, 1864. Left, James’s son was to make a name for himself in the Sussex cattle world, but his father seems to have preferred sheep. The affinity the family had to Sussex extended to Southdown sheep as well as the cattle. What does this experiment tell us? First of all, the Braby scientific mind was as fertile at the end of life as when younger (the same will apply to his son, as seen in the next chapter). Secondly, and selfevidently from the result, the experiment clearly sets out, apparently successfully, to demonstrate the superiority of supplementing the sheep’s hay and roots with malt, rather than the more usual barley, over the lean late winter months. However, modern research suggests the opposite. Malt and brewers’ grains provide less energy than barley, and there is a likelihood that too much (>10%) will depress feed intake because their high unsaturated fatty acid content reduces fibre degradation in the rumen. For this reason, brewery and distillery by-products are better used as feed for mature cattle, than for sheep or calves (MAFF, 1990). However, in the 1860s widespread experimentation was taking place. Isaac Seaman, writing in The Farmer’s Magazine, 1868, states: “the superiority of malted over raw grain; the former is harmless if eaten to excess; the latter poisons in the small quantity of a pint taken at one meal”. This seems to be untrue! Scientific feeding of livestock was in its infancy in the 1860s. Right - H&GDR Co share certificate No 1105, owned by William McCormick, fellow promoter with James Braby and Thomas Child. Left - Post card, Rudgwick Station c1905, Built on James Braby’s land His interest in railways was a theme of his business life. He was involved with the construction of plant for the first Irish railway from Dublin to Kingstown in 1831-4, the contractor for which was William Dargan, Braby’s almost exact contemporary. He became an intimate friend of Brunel, one of a select group accompanying him on 4 June 1838 to Maidenhead and back on the occasion of the first trip on the new Great Western Railway. No wonder, then that along with Thomas Child and William McCormick, James was one of the promoters of the Horsham and Guildford Direct Railway Act, 1860. The LB&SCR crosses Rudgwick, 1880. James Braby owned Greathouse Farm, which included the site of the station and the Martlet Inn. His land stretched from the southern edge of the map to ‘Linnick Street’. Child’s daughter Jane was already married to James’s nephew, his brother John’s son, Frederick. In the route survey, James was the owner of much of the route in Rudgwick, which crossed 24 of his fields, between the River Arun and Baynards Tunnel, mostly part of Greathouse Farm, farmed by Henry Jenkins, son of the former landlord of the King’s Head. Other local landowners were Edward J Bunny (Swaines Farm), Sarah Holmes (Hobbs Barn), Samuel Nicholson (Woodsomes) and Revd Thurlow at Baynards. The Brabys clearly benefitted financially from the acquisitions of the railway company, even though it would cut the land in two. His death was on 3 August 1865, so he would not have lived to see the railway opened. The railway company, LB&SCR, was bound by an agreement with Mr Braby “to make and for ever maintain a station in the parish of Rudgwick”. On 2 Oct when the line opened, it was clear there was a gradient problem at Rudgwick Station. Approval for its opening was not forthcoming from Col Yolland of the Board of Trade. Villagers were in doubt about the future of their station. Rudgwick Parish News, reported in West Sussex Gazette, 28 Sep 1865, wrote “J Braby of Maybanks, through whose land a great portion of the line in the parish passes, has built at great expense a large and commodious Inn for the accommodation of the railway passengers, which would be comparatively useless if the station is not opened.” Yolland insisted that Rudgwick station could not be opened as the gradient that it was built on (1 in 80) was too dangerous, and it needed to be flattened to 1 in 130. This didn't sound too much of an ordeal, but it meant that the bridge over the river Arun had to be raised considerably, and it was already part built. The part built embankments were raised and the brick arch that was under construction was left as a flying buttress to a new plate girder bridge. The station was finally opened in November 1865. One imagines that James and Emma Braby must have been prominent in this event, perhaps too his uncle John, James Child, Frederick and Jane Braby were in attendance. The Vestry Minute Book 1799-1859 (WSRO, PAR160/12) refers to James in 1855, 1858 and 1859 proposing motions and in 1859 elected to the Highway Committee. Alan Siney’s transcription of the 1860-94 Vestry Book (WSRO 2000) shows that James (4) continued an active member of the Vestry (the parish committee that was the forerunner of both the parish council and the parochial church council, and which met in the church vestry, usually adjourning to the King’s Head). The book opens with him proposing Henry Jenkins, churchwarden, and his tenant farmer at Greathouse, as chairman in March 1860. Subsequently he stays on the committee for highways (1860), is an overseer (1863), and once, in 1862, chairman. His presence in the community is a ‘first’ for the Brabys, and as lay Rector, one imagines the vicar was pleased to have him. He spent just eight years at Maybanks. He died in Brighton, according to his death certificate, so it would seem likely that the family already owned property there. Later, his son and grandchildren also lived, and some died, in Hove. James was buried alongside Mary Ann at Rudgwick under a large table tombstone with the Braby coat of arms on one end. The stained glass window (also containing the coat of arms) above the alter in Rudgwick church was dedicated to James and Mary Ann Braby’s tomb, Rudgwick, 1865 their memory by his son, James (5) before 1870. There is no evidence that James Braby (4) used these arms himself, which were, “or a chevron gules between three martlets sable”, and a motto, ex industria decus, ‘by labour with honour’. The arms are those of an old Herefordshire family called Breynton or Brenton. As there is no written source for Braby arms before 1905 (James Fairbairn, “Fairbairn's book of crests of the families of Great Britain and Ireland (Volume 1”), the possibility that one of the James Brabys purloined these arms for themselves is entirely possible, and not that unusual! The Braby arms on the tomb pictured above. The Breynton arms One can imagine him looking through an alphabetical listing, such as Burke’s General Armoury for his own name, and alighting on Breynton on the same page, perhaps struck by the reference to martlets which he would have known of in the Sussex county arms. c. The Churchman connection The map (1874-80) below shows the geographical relationship between Maybanks (west), Berry House (east) and Rudgwick village and church (southwest) [www.old-maps.co.uk]. Maybanks drive can be seen heading south to Cox Green and Rudgwick, replacing an earlier entrance The Churchmans were successful yeoman farmers, and all of Mary Ann’s brothers became farmers of large farms in Sussex and Surrey, and most relevantly for this article, one was Maybanks, near Cox Green in Ewhurst. A number of prominent Churchman graves can be seen in Rudgwick churchyard. Like the Brabys after them they found Maybanks location and ownership of land in Rudgwick had oriented them to Rudgwick church. The Churchmans came from Slinfold. Mary Ann’s great great grandfather William, a yeoman (1655-1738), married Mary Dendy and is the first to have farmed Berrylands in Rudgwick in 1701. Maybanks appears as freehold in the manor of Pollingfold, which was a sub manor of Gumshall Netley. The Churchmans were an influential family owning Southlands, which had been part of Pollingfold, and Sansomes, Pipers, (Ellens Green) and other land in Abinger, Rudgwick, and Slinfold. His son, John, a gentleman (1694-1771) married Jane Butcher (same family as Frusannah Braby’s forst husband) and was the first Churchman to farm Maybanks, then called ‘Mabings’ (probably pronounced ‘May-bings’), which he had mortgaged in 1741, and purchased outright in 1749, from Timothy Butt. John rebuilt Mabings, to make it fit for a gentleman - the property was first documented 1503) - now “a double pile house with four rooms on the ground floor and two backing hearths” (Balchin, 2006), but continued to hold Berrylands for his son William until he was of age. In 1771, he left ‘Mabbanks’ to his daughter, Ann who then sold it to her younger brother (John’s eldest son), William. “To daughter Ann Churchman – Mabbanks, Dunstalls Stubb and Mascalls, also Broad Meadow, part of Sansums and Bumpers Platt part of Southlands subject to an annual payment of £20 to her brother William Churchman”[Will]. John’s will, 1772, shows he owned Waterland Farm, Slinfold, Aylewards & Southlands Farm, Mabbankes, Dunstalls Stubb, Mascalls and other lands in Ewhurst (see manorial records below). William (1735-1789) was ‘admitted’ (in the manorial court) to Berrylands in 1762, aged 24, after which he then rebuilt Berrylands (often then referred to as Berry House). William, who was firstly married to Sarah King (Mary Ann’s grandmother), and secondly to Hannah Briggs, inherited Maybanks from his father in 1771. Ownership is uncertain between 1789 and 1793. Next, in 1789, Mary Ann Braby’s father, John Churchman (1770-1816, see above), inherited Maybanks. In the 1793 articles of agreement of marriage of John Churchman of Ewhurst, gent, to Ann Ireland of Rudgwick spinster daughter of Thomas Ireland, yeoman, signed by Thomas Ireland & William Briggs of Slinfold tanner, the properties of Pollingfold, Coxlands & Maybanks in Ewhurst and Abinger were assigned to the couple (Balchin). He and Ann added the north wing to Maybanks. The barns and stables form part of an 18th Century planned farmyard. A page from the family bible of Thomas Ireland, father of Ann Churchman. The births of Mary Ann and Maria Braby, nee Churchman, are recorded in 1799 and 1808. Mary Ann’s death is also recorded (1828). Mary Ann’s eldest brother, also John (1794-1857), married Elizabeth Agate, inheriting Maybanks (230 acres) in 1816. In his father’s Will – “To son John - Mabbings otherwise Maybanks, in which they do dwell and which he [the testator] purchased from Richard Yaldwin Esq.* also Broadmead and Bumbers Platt part of Southlands” [*Richard Yaldwin sold Sharpes to John Churchman in 1800; he does not appear in any other Maybanks document, probably named by mistake.] This is confirmed in the Pollingfold manorial record in 1833, 1839 and 1844 (“John Churchman holds”). In 1842 (tithe award, John Churchman), the farm was 242 acres. The second son, William, went to Loxwood Place Farm, Loxwood, Sussex (a King farm), and was left Mill Farm Rudgwick in 1816, the third Edward inherited Berrylands, later farmed in Lydling near Godalming. Frederic inherited Sansomes (where he farmed), Coxlands and Pipers. All legacies were subject to an annuity to testator’s wife, and legacies to daughters Mary Anne, Caroline, Elizabeth and Maria. Mary Ann Braby was the eldest daughter. Caroline, her younger sister, married Thomas Child of Slinfold, a marriage which would later provide a daughter, Jane, who married Frederick Braby. Maria married James Braby (4)’s brother, John. Elizabeth married Henry Allberry, the Rudgwick (Wanford) miller. John and Elizabeth’s eldest child, another John, born 1818, did not inherit Maybanks. He farmed in Leigh, Surrey for a while but then went to Tooting to manage a grocery shop! One suspects he had not inherited the best family genes. His several sisters, one imagines, were not deemed suitable (and were not born until the 1820s and 30s). Bearing in mind Mary Ann’s father had died before her marriage to James Braby, were John Churchman and his brothers sufficiently impressed by their sister’s marriage to James Braby, that Maybanks passed to her, and then to her husband, perhaps by a marriage settlement for which no document survives? This was suggested by Janet Balchin. In her Maybanks house history for Ewhurst Historical Society, 2003, she has also discovered the following in manorial records, which suggests another scenario:In the manor of Pollingfold Court Book, John Churchman alienates (sells) property in the manor of Gumshall Netley to a Mr Braby in 1842, but the part referring to Maybanks itself asserts that John Churchman is owner until after 1844, the last mention of Maybanks. The fields named Maskels, Dunstalls, Wythiat, Ruet, Broadmead (not Southlands) in Gomshall Netley are part of Maybanks in 1842 tithe schedule, which strongly suggests that Braby is acquiring ownership of the farmland, if not the house, perhaps immediately after the tithe survey was completed. James (3) died in 1846. It is conceivable he was the one named, but it was his son who had married a Churchman, and may have been provided for in advance of his father’s will, which makes no mention of any property apart from those connected with the Lambeth business. James (4) was the certain owner of Maybanks itself from John Churchman’s death in 1857, and, later James (5) in 1866. Manorial records are normally postdated to the next meeting of the court. Re freehold lands called Mabbanks rent 16/- and other lands called Maskals [two fields in Maybanks tithe schedule)] rent 8d., Manor of Pollingfold Re Dunstalls [2 fields in Maybanks, as above], Wythiat [field called Woolwich, as above) & Ryewirth alias Sydneys [2 fields called Ruet, as above], Manor of Gomshall Netley 1842 – “Alienment John Churchman to W Braby – enquire parlay as to the Deed”. 1848 – “The Deed as to heriots dated 17 Feb 1763 produced & presented £5.12.6. due for heriots? for ? on the alienation to Mr Braby”. 1866 – “His death – his son James Braby holds”. 1867 – “Deed of Enfranchisement”. [enfranchisement is release from manorial obligations] Re Southlands [?adjacent to Hawks Hill, Rudgwick], & Bonnsers or Bombers Mead [field called Broadmead, as above], part of [East] Pollingfold, Manor of Gumshall Netley 1842 - “Alien by John Churchman to Mr Braby – enquire parlay as to the deed respect of Heriots” 1848 - “The deed as to heriots dated 17 February 1763 produced & presented. £5.12.6. due for heriot certain for 1 ? on the alienation to Mr Braby”. 1866 - “His death – his son James Braby holds”. 1867 - “Deed of Enfranchisement discharged 1867”. John Churchman’s mother, Ann, had removed to Kings, a house on the main street of Rudgwick. She died in 1843, aged 73.