development of perception

advertisement

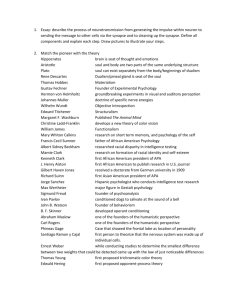

DEVELOPMENT OF PERCEPTION To read up on perceptual development, refer to pages 88–101 of Eysenck’s A2 Level Psychology. Ask yourself How much do you think a newborn baby can see and hear? What evidence is there that perceptual development is due to nature? What evidence is there that perceptual development is due to nurture? What you need to know INFANT STUDIES INTO THE DEVELOPMENT OF PERCEPTUAL ABILITIES Depth/distance perception Visual constancies: size constancy; shape constancy INFANT AND CROSSCULTURAL STUDIES OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF PERCEPTUAL ABILITIES Does the improvement in visual acuity over time depend on learning or maturation? What cross-cultural differences are there in perception? NATURE–NURTURE DEBATE IN RELATION TO EXPLANATIONS OF PERCEPTUAL DEVELOPMENT Is perception innate or learned? INFANT STUDIES INTO THE DEVELOPMENT OF PERCEPTUAL ABILITIES Depth Perception Gibson and Walk (1960, see A2 Level Psychology page 89) developed the “visual cliff”, which was a glass-top table, underneath which a check-patterned cloth was positioned. A “shallow” side was created by positioning the cloth close to the glass under one half of the table, and positioning the cloth further away on the other half created a “deep” side. Infants between the ages of 6½ and 12 months were tested for depth perception by placing them on the shallow side and seeing if they could be tempted to cross to the deep side. Most infants could not be tempted by their favourite toy nor their mother’s voice, which suggests that depth perception develops by approximately 6 months, as the babies were reluctant to cross to the “deep” side. However, Adolph (2000, see A2 Level Psychology page 89) argued that the development of depth perception is more complex than assumed by Gibson and Walk (1960, see A2 Level Psychology page 89). She argues that infants do not acquire general knowledge (e.g. an association between depth information and falling) that stops them from crossing the visual cliff; instead the infants’ knowledge is highly specific. According to this model, infants learn how to avoid risky gaps when sitting, but subsequently have to learn how to avoid such gaps when they are crawling. Adolph (2000, see A2 Level Psychology page 89) provided evidence that learning with the visual cliff is specific to a given posture (e.g. sitting) and new learning is needed when infants become more mobile. This leads to the conclusion that learning to avoid gaps is specific to a given posture (sitting and crawling) in younger infants but becomes more general in older ones, because they are able to transfer depth learning from crawling to walking. However, research on retinal image size in infants under 2 weeks old (Bower, Broughton, & Moore, 1970, see A2 Level Psychology page 90) does provide evidence of innate perceptual abilities. The two different size objects had the same retinal size due to being different distances away from the infant, yet the infants were more distressed by the objects that came closest to them, which shows that they were able to perceive depth from a very young age. Visual Constancies Size constancy is when an object is perceived to be the same size regardless of distance, and shape constancy is when an object is perceived to be the same shape regardless of orientation. Size Constancy A size constancy task (Bower, 1966, see A2 Level Psychology page 90) was developed based on initially presenting infants with a 30cm cube placed 1 metre from them. Infants were then presented with the same cube placed 3 metres away and a 90cm cube placed 3 metres away. Size constancy was shown to some extent as the infants spent longer looking at the cube that had the same size as the initial cube despite the fact it had a much smaller retinal image. But they failed to show complete size constancy as they attended to cubes placed 1 metre away more then cubes of the same size placed 3 metres away. Shape Constancy The habituation method involves presenting a stimulus until the infant no longer attends to it. Once habituation has occurred, a new stimulus is presented, and if the infant attends to this then discrimination has occurred. Infants aged 3 months were presented with a square that formed a trapezoidal shape on the retina. This was presented until habituation occurred. They were then presented with a real trapezoid and their interest showed they had habituated to the real shape and not the retinal image. This is evidence that shape constancy has developed in 3-montholds despite inconsistency with the retinal image (Caron, Caron, & Carlson, 1979, see A2 Level Psychology page 91). This research shows that the infants habituated to the real shape of the object rather than to the object shape projected onto the retina. This strongly suggests that these infants had developed at least partial shape constancy. EVALUATION Limitations of the measures. The habituation measure indicates discrimination and the visual preference method indicates which stimuli are preferred, but they do not reveal how the stimuli are perceived and interpreted. Similarly, the visual cliff method shows that the deep side disturbs infants but this does not reveal how they perceive depth. Thus, the measures lack precision and, to some extent, validity as they are not true indicators of perceptual processes. But this, of course, is due to the difficulty of investigating “unobservable” cognitive processes and so the measures are useful, given these difficulties. Mundane realism and ecological validity. The stimuli shown to children and the experimental set-up led to a lack of mundane realism. For example, the stark contrast between the “deep” and the “shallow” side of the visual cliff is rare in real-life environments, and the mother would be unlikely to tempt the infant into a dangerous environment. Thus, external validity is limited. Nature or nurture. It would make evolutionary sense for perceptual abilities to be biologically driven. However, the research evidence does not clarify this as research is often based on infants a few months old who will have learned some of the perceptual skills, but maturational factors may also be involved. Ethics. The babies in the “visual cliff” study experienced discomfort. Do the ends justify the means? INFANT AND CROSS-CULTURAL STUDIES OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF PERCEPTUAL ABILITIES Infant Studies RESEARCH EVIDENCE Infants have very poor visual acuity. We can assess visual acuity by presenting a display of alternating black and white lines, and then making the lines progressively narrower until they can no longer be separated in vision. In order for newborns to detect the separation of the lines, they need to be about 30 times wider than is the case for adults (Braddick & Atkinson, 1983, see A2 Level Psychology page 92). Another visual limitation in newborns results from the fact that they don’t show accommodation. Their eyes have a fixed focal length for the first 3 months. This means that they can only focus clearly on objects at a given distance from them (about 8 inches). Newborns lack colour vision as this does not begin to develop until 2 months. Newborns are deficient in binocular vision, which involves using the disparity or difference in the images projected on to the retinas of the two eyes to assist depth perception. Teller (1997, see A2 Level Psychology page 92) reviewed evidence suggesting that binocular vision is first found in infants between the ages of 3 and 6 months. Banks, Aslin, and Letson (1975, see A2 Level Psychology page 93) studied adults who had had a problem with binocular vision because of having a squint in childhood that was subsequently corrected. They found that the later this was corrected, aged 4 plus, the less binocular disparity they had as adults. These findings suggest that there is a critical or sensitive period for the development of binocular disparity during the early years of life in older children and adults. However, visual acuity in adults with amblyopia (impaired vision due to disuse of an eye with no obvious damage to it) can be improved if they receive prolonged practice on a difficult visual task (Levi, 2005, see A2 Level Psychology page 93), indicating that learning can be important. There is evidence infants are innately programmed to recognise human faces. Morton and Johnson (1991, see A2 Level Psychology page 93) argued that human infants are born with a mechanism containing information about the structure of human faces. This mechanism is known as CONSPEC, because the information about faces it contains relates to conspecifics (members of the same species). Johnson et al. (1991, see A2 Level Psychology page 93) found that newborns in the first hour after birth showed more visual tracking of realistic faces than of scrambled but symmetrical faces in which facial features were moved to unusual locations within the face. This supports the influence of nature over nurture in face perception. However, Turati et al. (2002, see A2 Level Psychology page 93) claim there is nothing special about faces. Instead, newborns simply have a preference for stimuli having more patterning in their upper than in their lower part. This contradicts an innate bias for faces. In a replication of research into scrambled versus natural faces Simion et al. (2006, see A2 Level Psychology page 94) also found that newborns prefer scrambled faces with more elements in the top area to natural faces. However, 3-month-olds preferred facial stimuli to scrambled faces. This leads to the conclusion that cognitive mechanisms specialised for faces develop over the first few weeks or months of life. EVALUATION Scientific support. There is strong evidence that it does take several months for some of the basic mechanisms involved in vision to function effectively. Difficult to research infants. It is of course difficult to research infants because we cannot ask them what they see! This leads to a great deal of controversy over whether they do actually have an innate bias for faces or not. We have to rely on indirect evidence based on their behaviour, their gaze patterns, and so on, from which not all conclusions may be valid. Cross-cultural Studies RESEARCH EVIDENCE Segall, Campbell, and Herskovits (1963, see A2 Level Psychology page 94) found that the Müller–Lyer illusion was dependent on experience of a “carpentered environment”, which is an environment made up of mainly vertical and horizontal lines and so mainly made up of rectangles. A rural Zulu community did not show the illusion because they had no experience of such an environment. A comparison of Canadian Cree Indians who lived in cities and those who lived in tepees showed that when asked to decide if two lines were in parallel, the tepee dwellers were successful no matter what the angle of the lines, but the city dwellers were better when the lines were horizontal or vertical. This shows the importance of past experience to visual perception and so supports the role of learning in perceptual development (Annis & Frost, 1973, see A2 Level Psychology page 95). Allport and Pettigrew (1957, see A2 Level Psychology page 95) demonstrated the importance of experience in their study of a visual illusion. They created a “window”, which was trapezoid in shape and fitted with horizontal and vertical bars. It was then rotated in a circle, which gave the illusion that a rectangle was moving backwards and forwards. However, only participants who lived in cultures with rectangular windows experienced the illusion. Those without such environmental experience, e.g. Zulus living in rural areas, did not see the illusion because they were not predisposed to look for rectangular shaped windows. Gregor and McPherson (1965, see A2 Level Psychology page 95) provide evidence that an absence of a carpentered environment does not necessarily lead to an inability to see visual illusions. They compared two groups of Australian Aborigines. One group lived in a carpentered environment whereas the other group lived in the open air and had very basic housing. The two groups didn’t differ on either the Müller–Lyer illusion or the horizontal–vertical illusion. Cross-cultural differences in visual illusions may depend more on training and education than on a carpentered environment. Hudson (1960, see A2 Level Psychology page 96) investigated perception of simple two-dimensional drawings. He found that non-Western societies had difficulty perceiving three-dimensional scenes in such drawings, whereas Western participants had no difficulty with depth perception. Deregowski, Muldrow, and Muldrow (1972, see A2 Level Psychology page 96) found that members of the Me’en in Ethiopia didn’t seem to recognise drawings of animals on paper. This might suggest that they had poor ability to make sense of two-dimensional representations. However, when the Me’en were shown animals drawn on cloth (a material familiar to them), they were generally able to recognise them. EVALUATION Generalisability. Small samples are a common weakness of cross-cultural research and as the target population is usually restricted the findings are not very representative. Ethnocentric tasks. The two-dimensional picture perception is a culturally specific task as these were based on Western drawing styles and used Western materials. Deregowski, Muldrow, and Muldrow found that the Me’en culture in Ethiopia did not respond to drawings on paper but did to drawings on cloth, as this was a material more familiar to them. Thus, we must be cautious in drawing conclusions on cultural differences in perception as the findings may be biased by ethnocentrism. The “carpentered environment” is also ethnocentric, as experience of an environment made up of mainly vertical and horizontal lines depends on culture. Difficult to interpret findings. Different cultures vary in many ways and so it is difficult to interpret the source of the cultural differences in perception. This makes it hard to draw conclusions, particularly given the problems of ethnocentrism. Linguistic barriers may decrease validity. The cross-cultural variations may be due to language differences, which mean that perception is not reported in the same way, but this does not mean that they are not perceived in the same way. Thus, differences may be a consequence of language rather than actual perception and so validity would be low, as the research would not have measured what it set out to. Weaknesses of self-report. Self-report is vulnerable to researcher bias and participant reactivity. For example, researcher expectancy or cueing may have yielded demand characteristics and so led the participants, which means internal validity is questionable. Mundane realism and ecological validity. Most cross-cultural research has focused on two-dimensional visual illusions, which are often Western-biased, e.g. the “carpentered environment”, and are not relevant to everyday perception. This means the cultural differences found lack mundane realism. This is a significant weakness as research could instead have focused on different visual stimuli, which may demonstrate cultural differences with more relevance to real life. Instead the research may tell us very little about cultural differences in everyday perception. NATURE–NURTURE DEBATE IN RELATION TO EXPLANATIONS OF PERCEPTUAL DEVELOPMENT RESEARCH EVIDENCE Evidence for the role of nature in perceptual development is that some aspects, e.g. aspects of face perception; aspects of size and shape constancy; dominance of global over local features, seem to be present at birth or very shortly thereafter. This suggests these are innate visual capacities or very rapid learning. Some aspects of visual perception emerge a few weeks after birth, e.g. visual acuity and colour vision, and so seem to involve maturation, which means the behaviours are instinctive but only emerge at a particular point in development. Other aspects seem to develop in a critical or sensitive period, e.g. binocular disparity. This suggests the involvement of genetic factors and so nature. The substantial improvements in infants’ perceptual abilities in a fairly short time period from birth points to the importance of maturation, i.e. that perceptual abilities are genetically predisposed but require a certain amount of physical development before they are realised. For example, infants’ visual acuity is about one-fortieth that of adults, and typically reaches the adult level around the age of 12 months. It is likely that the large increase in neurons in the visual cortex occurring during the first 6 months of life plays a major role, and so this physical maturation is needed before the predisposed ability can fully develop. Other aspects of visual perception take months to develop, e.g. depth perception, and so this suggests the role of learning (nurture). The significant cross-cultural differences also support the role of learning as they suggest that experience (i.e. learning) of the environment shapes perceptual development. Evidence for the role of learning is provided by distortion studies. G.M. Stratton (1896, see A2 Level Psychology page 98) tested the effects of wearing a lens on one eye that turned the world upside down (he kept his other eye covered). At first everything looked unreal, but within 5 days he reported he could write and walk around with relative ease. He took the lens off after 8 days and because everything was now a reversal of what he had grown used to it also required some readjustment time. Thus shows the visual system is not completely fixed because it was able to adapt to such a changed environment. However, the fact that Stratton’s visual system was fairly intact after 8 days of distortion can be used to support an innate basis as clearly any learning did not have a lasting effect. Further evidence as to whether perception is innate or learned is provided by readjustment studies, which involve individuals born blind because they have cataracts who then have those cataracts removed. These provide useful insights because their visual system has had no learning experience and so any abilities they have initially must be due to nature. To a great extent nurture has been controlled! Gregory and Wallace (1963, see A2 Level Psychology page 99) documented the case history of SB. SB did not show depth perception, nor could he recognise visual illusions, and in fact continued to use his hands to “see” as touch was the sense he was most accustomed to using. Maurer, Lewis, and Mondloch (2005, see A2 Level Psychology page 99) discussed the findings from people who had cataracts removed when they were only 2 or 3 months old. Many of their visual abilities were normal but there was impairment in the more complex aspects that take the longest to develop. They were poor at recognising faces from different viewpoints, at discriminating between faces that only differed in terms of the spacing among facial features, and at detecting small differences between shapes. These long-lasting deficits support the importance of learning from early visual experience. However, the fact that more simple visual abilities (e.g. distinguishing between simple shapes, discriminating a face from a scrambled image, and discriminating between faces that differed in various ways from each other) were not impaired suggests that visual experience is not necessary for their development. EVALUATION Reductionism. It would be reductionist (oversimplified) to assume perceptual abilities are due to either nature or nurture. Most perceptual abilities depend on both nature and nurture, with the relative contributions of each varying from one perceptual ability to another. Our current understanding of maturation suggests that the brain requires input to mature. Thus, it is nature and nurture. Difficult to interpret adult readjustment studies. The evidence is difficult to interpret because the absence of perceptual development does not necessarily reject the influence of nature. The brain areas responsible for visual processing may have degenerated or been used to facilitate the use of touch. The use of touch may interfere with the development of visual abilities. There is also the problem of motivation. For example, SB preferred to rely on his sense of touch because he found vision difficult and frustrating. Adaptive. The cross-cultural studies provide evidence of visual development being specific to environment and this is of course adaptive because it makes evolutionary sense for an individual to adapt to the requirements of the environment as this will increase his/her chances of survival. Perception requires understanding. Some basic visual abilities are mainly innate such as visual acuity and colour perception. However, understanding what has been perceived is only possible with learning from the environment, and so shows that meaningful perception depends very much on nurture. SO WHAT DOES THIS MEAN? The infant studies support the influence of nature as these suggest that many perceptual abilities are innate. But the cross-cultural studies show that perceptual organisation is not universal and this cultural variation points to the role of nurture. In conclusion we are innately (nature) programmed to respond to experience (nurture) and so an interactionist approach is needed to fully understand perceptual development. It is impossible to separate out nature and nurture as the innate schemas are influenced by experience and we are predisposed to seek out and adapt to experience. We are born with neurophysiological systems that need to interact with the environment for maturation to take place. OVER TO YOU 1(a). Describe and evaluate one study of the development of perceptual abilities. (10 marks) 1(b). Describe and evaluate one explanation of perceptual development. (15 marks) 2. Discuss the nature–nurture debate as it applies to perceptual development. (25 marks)