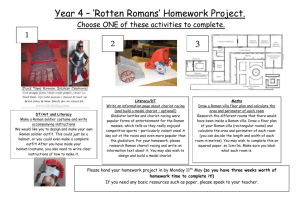

Template: Main Text

advertisement