Reading Between the Lines: Multidimensional translation in tourism

advertisement

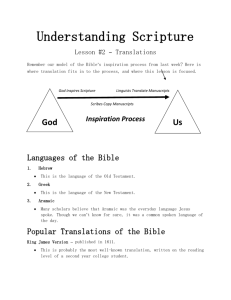

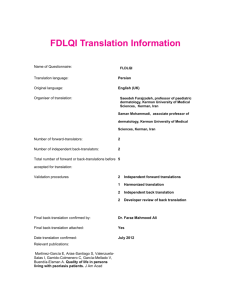

READING BETWEEN LINES: THE MULTIDIMENSIONAL TRANSLATION IN TOURISM Professor Gillian Hogg Professor Gillian Hogg is Pro-Vice Chancellor of Heriot-Watt University. Her research interests are consumer behaviour, in particular consumers use of the internet as an information source and use of that information in non-internet situations. With colleagues in Loughborough and Manchester Universities she was part of the ESRC Cultures of Consumption programme looking at professional services and the internet and this current research extends this research into the area of language. Dr Min-Hsiu Liao Dr Min-Hsiu Liao is a lecturer at the School of Management and Languages, Heriot-Watt University. Her research interests lie in discourse-based translation analysis and interaction in communication. Her studies cover the issues of the spread of culture (how the discourse from one culture influence that of another), such as in the genre of popular science; and culture conflict, such as the display of Chinese art in British museums. She has also engaged in interdisciplinary collaborations, in which discourse analysis is used as a tool to uncover attitudes and perceptions embedded in discursive events, such as in mathematic classes. She has published in The Translator, The Journal of Specialised Translation, and The International Journal of the Arts in Society. Professor Kevin O’Gorman* Professor Kevin O’Gorman is Professor of Management and Business History in the School of Languages and Management in Heriot-Watt University, Edinburgh. His current research interests have a dual focus: Origins, history and cultural practices of hospitality, and philosophical, ethical and cultural underpinnings of contemporary management practices. He has published over 70 journal articles, book chapters, editorials, reviews and conference papers and recently published a book 'The Origins of Hospitality and Tourism'. This is the first book to explore in-depth into the origins of hospitality and tourism, focusing on the history of commercial hospitality and tourism from Classical Antiquity to the Renaissance. *Corresponding Author School of Management and Languages Heriot-Watt University Edinburgh k.ogorman@hw.ac.uk 1 READING BETWEEN LINES: THE MULTIDIMENSIONAL TRANSLATION IN TOURISM Abstract This paper argues that for translation to enhance the tourist's experience literal accuracy is not enough and translations should be culturally sensitive to their target readers. Using the example of museum websites as a form of purposive tourism information designed to both inform and attract potential visitors, this paper analyzes websites of museums in the UK and China. We argue that no matter how accurate a translation may be, if the norms of the target tourist community have been ignored a translation may fail to achieve its purpose and may even have a detrimental effect on the tourism experience. By bringing together translation and tourism theory, we demonstrate when the cultural element of tourism is considered alongside the translation of texts, the need for linguistic accuracy is superseded by a requirement for cultural sensitivity. Key Words Translation theory; Culture; Text; Genre Highlights Move translation from literal dimension to a cultural dimension Introduce translation theory and genre analysis to tourism management Demonstrate the importance of cultural awareness when translating texts Show that linguistic accuracy is superseded by a requirement for cultural sensitivity 2 READING BETWEEN LINES: THE MULTIDIMENSIONAL TRANSLATION IN TOURISM A key element in effective tourism communication is translation of information that tourist destinations provide to their visitors. The effects of translation on this information, however, are under-researched in the tourism literature and similarly there is little discussion of tourism material in translation studies research. Where research exists, focus tends to be on the quality of translation in a literal sense, i.e. the accuracy of meaning or the fluency of the writing, rather than how the translation conforms to the norms of the target culture (some exceptions are Kelly, 1998; Mason, 2004; Snell-Hornby, 1999; Hu 2011). Fundamentally, tourism is a cultural experience and therefore effective communication must be sensitive to cultural sensibilities (Prentice and Andersen, 2007; Pritchard and Morgan, 2001; Ryan and Gu, 2010). Within tourism research, little consideration has been given to the impact of translation or the norms of the target culture when conducting fieldwork. An exception to this is Yang, Ryan, and Zhang (2012) who highlight the importance of appropriate cultural sensitivity when conducting tourism research in China. In this paper we argue that for translations of tourist information to enhance the tourist's experience, literal accuracy is not enough and translations should be multidimensional i.e. culturally sensitive to their target audience and take account of the considerable theory now available in translation studies. In this paper we use translation theory to explore this theoretical gap in tourism research by examining the translations contained within websites of internationally renowned museums in China and the UK. Museum websites provide a useful context for this research as they are universal, easily accessed and designed to both inform and attract potential visitors. We argue that no matter how accurate a translation may be, if the norms of the target community have been ignored it is a poor translation, and may even have a detrimental effect on the tourist experience. As well as filling this theoretical gap, a further aim of this paper is to allow practitioners to ensure that their translations are accurate and fluent, but vitally also considerate of the target culture. 3 Tourism and Translation Issues Previous research into translation issues in tourism falls into two categories; issues regarding the translation of tourism information, e.g. brochures, guides, websites etc. and the challenges of conducting tourism research that relies on translation. Within multiple language tourism research the focus tends to be on back to back translation of survey instruments or questionnaires (see for example Kim and Morrsion, 2005; Lam, Zhang, and Baum, 2001; Li and Stepchenkova, 2011). An exception is Ryan and Gu (2010) who explored the tensions when engaging with a festival through translation with different perspectives. Zeng and Ryan (2012) note that conventional linguistic and possibly conceptual difficulties of translation causes Chinese research not to be acknowledged internationally, they highlight the example of tourism development specifically targeted at the reduction of rural poverty being known as fu pin lv you 扶贫旅游 or lv you fu pin 旅游扶贫, which could be translated in English as ‘Tourism Assisting the Poor’ (Zeng and Ryan, 2012). This is similar to the Western concept of Pro-Poor Tourism (Butler, Curran, and O'Gorman, 2013), but the large volume of literature produced in China has been overlooked due to lack of translations, or even awareness of its existence. Another phrase is similar conceptually but also has a role in promoting human health, therefore Buckley et al. (2008) argue that shengtai lvyou 生态旅游 (e.g. in Zhang, G.,1999 ) is thus a cultural analogue of ecotourism, not simply a translation. Furthermore, due to the difference in these terms both etymologically and culturally, any computerised search using the literally translated words would not yield any results. Translation in tourist publications occurs in a literal dimension with a focus on back to back translation as poor translation has been shown to have a negative effect on tourist choice, for example, it is seen as a barrier to participation in tourist activities (Allison and Hibbler, 2004; Yang, 2009) and can make destinations unattractive (Chen and Hsu, 2000). Recently there has been a focus on using technology to improve the accuracy of translation rather than a wider engagement with translation practices (for example Ho, 2002; Li and Law, 2007). Little reference is made to using experts in translation or acknowledging the existence of translation theory or methods. The implicit assumption within the literature is that translation is a stock process that must be executed in a bureaucratic fashion without critical thought or consideration to the developments within translation theory itself. From a translation perspective, much of the tourism literature's engagement with the process is presumptuous and unsympathetic to the broader implications and effects associated with translated text. The adoption of rigorous translation theory within tourism 4 research has the potential to deepen our knowledge of the tourism experience itself as well as offer practical contributions to its operationalisation. Translation Theory At its simplest translation refers to the relationship between the source text (ST) and the target text (TT). This intertextual relationship was formerly explored through the concept of equivalence. One of the leading figures in this field defines translation as "the replacement of textual material in one language (SL) by equivalent textual material in another language (TL)" (Catford, 1965, p. 20). Although equivalence is an easily applied concept, it has been criticized widely among translation scholars for naively assuming symmetry between languages as if all translators need to do is to find the ‘right’ word (Snell-Hornby, 1988; Wang, 2003). More recent translation research has considered translation as a process rather than a product. The process of translation is not to find the corresponding words in another language, but involves a series of decision making and consideration of the uses and users of the translations. Hu (2003, 2011), for example, in his theory of ecological translation advocates that adaptation and selection are a "translator's instinct as well as the essence of translating" (Hu, 2003, p. 284). As to what constitutes the base for selection and adaptation in the translation process, a common view is that the purpose of the translation should govern the decision-making (e.g. Nord 1991, 1997;Zhang, M., 2005). This moves away from linguistic equivalence to the functional theory of translation, which advocates that a translation should be assessed in accordance with how appropriately it fulfills its intended function in the target context, rather than how faithfully it relays the source text meaning. In this paradigm translation is defined as "the production of a functional target text maintaining a relationship with a given source text, that is specified according to the intended or demanded function of the target text" (Nord, 1991, p. 28). The Functional theory of translation broadly categorizes two types of translation approach: documentary (which relays the ST meaning to the TT readers, and the readers are often aware that they are reading a translation); and instrumental (which retells the ST to the TT readers, and the readers may think that what they read were originally written in the target language). Under the two broad categories, a spectrum of forms of translations is presented in table 1, according to the distance from the source text. 5 Table 1. Forms of translation in the functional theory of translation (adapted from Nord 1997:48, 51). Documentary approach Instrumental approach Distance from the source text Form of Interlineal translation translation Literal translation Philological translation Eroticizing translation Purpose of Reproduction translation of SL system Equifunctional translation Reproduction of Reproduction of Reproduction of Achieve ST SL form ST form + ST form + functions for content content + target audience situation Focus of Structures of SL Lexical units of Syntactical units Textual units of Functional units translation lexis + syntax structure text of source text source text of source text process Example To provide To preserve To translate the To preserve To translate word for word quotations in Greek and Latin unfamiliar tourism translation in news texts in classics literally cultural information, the sentence the source text but with references recipes, order of the in and also explanation (such as foreign instructional comparative provide a gloss notes. names) in manuals as if linguistic translation modern they were studies. literature prose originally without written in the explanations in target order to give language. readers an exotic flavour. 6 Heterofunctional translation Homologous translation Achieve similar Achieve functions as homologous source text effect to source text Transferable Degree of ST functions of ST originality To translate for a different purpose from that of the source text; for example, Gulliver's Travels was originally intended for adult readers but has been translated into many languages for children. To translate a poem by a poet creatively; for example, to translate a Greek hexameter by an English blank verse. The form of translation mostly applied to tourism information is equifunctional translation in the instrumental approach, in which the TT maintains the same function of the ST but not the form of the ST. The equifunctional approach is often adopted because the ST and the TT tourist texts usually share the same goal, i.e. to attract and inform tourists. Although the means may be different across cultures and languages, the ultimate goal is the same. Furthermore, the translations are usually expected to function as an original text rather than informing the readers of what is in the source text. To produce a translation as if it were written originally, the translators need to be sensitive to the conventions or norms in which the translation will be situated. Several studies have compared the norms of English and Chinese tourism texts, and highlighted differences in various aspects, such as sentence structures (Xiong and Lin 2011; Wang, 2012), rhetoric style (Ye, 2008), and culture-specific lexis (Wu, 2004; Kang, 2005; Liu and Li, 2008). Jin (2004) comments on how the bureaucratic procedure involved in the translation of official tourism texts can be an obstacle and argues for a different mindset when dealing with tourism translation. To date, however, most studies comment only on linguistic differences at the text level, little attention has been paid to how a text achieves its function in the social context. For this reason translation scholars have developed the concept of genre analysis (e.g. Hatim and Mason, 1990, 1997). Genre is defined as the conventionalized form of texts which are derived from conventionalized forms of occasions; they encode the "functions, purposes and meanings embodied in those social occasions" (Hatim and Mason, 1990, p. 241). To achieve equifunctional translation, the translator needs to seek "equivalence" at the genre level, rather than in the linguistic level. To take the translation of tourism brochures as an example: if the aim of a translation is to achieve the same function as the source text, when the translation is presented to the target readers they should easily recognize the text as a tourism brochure, based on their experience with other tourism brochures in their mother tongue. This means that the translator may have to remove some parts of the source text or to add some features which are typical of the genre in the target language. Unlike the literal view of translation which takes the source text as the yardstick for translation decisions, translation in this functional view places less emphasis on the source text and more on the purpose of the translated text (Vermeer 1982, as translated in Shuttleworth and Cowie, 1997, p. 182). When considering the translation of tourism information therefore, we need to explore both the accuracy of the literal translation and the cultural expectations of the genre. 7 Methodology Data Collection: Creating a corpus Since the 1990s translation studies have adopted a corpus-based approach to explore texts and their translations. The purpose of a corpus, as explained by Hunston (2002, p. 20) is to tell us what language is like. The main argument in favour of using a corpus is that it forms “a more reliable guide to language use than native speaker intuition” (Hunston, 2002, p. 20). A native speaker “has experience of very much more language than is contained in even the largest corpus, much of that experience remains hidden from introspection”. Moreover, corpus linguistics was introduced as linguistic analysis and tended to be based on a researcher’s intuition. For example, if we want to see if the translated text conforms to cultural norms by relying on native speakers and their intuition we can establish that ‘this text does (not) look like a xxx in my country’. However, intuition is not always reliable and often cannot be explained. Corpora exist in different forms, from the large scale quantitative ones used to explore universal features of all translated texts (Ghadessy and Gao, 2001; Hu and Zhu 2008; Mauranen and Kujamäki, 2004; Olohan and Baker, 2000) to the smaller and more focused ones commonly used to investigate linguistic features in a specific genre (Bosseaux, 2004; Li and Wang 2009; Munday, 1998). In this research we have compiled a comparatively small corpus as these can “be honed to very specific genres and sub-genres" (Sinclair, 2001, p. xiii). In order to assess the quality of translations we compare websites with genres in the same language. To this end we compiled two sets of English and Chinese museum websites based on five leading museums. We used the websites of the Victoria & Albert Museum, London and the Capital Museum, Beijing subdivided into four distinct groups: the English source text of the Victoria & Albert Museum (VAM-ST) and its Chinese translation (VAM-TT), the Chinese source text of the Beijing Capital Museum, (BCM-ST) and its Chinese translation (BCM-TT). In addition we compiled a comparable English museum corpus (EMT) and a Chinese museum corpus (CMT). Table 2 shows word counts of the six groups under investigation. These have been segmented for the purpose of this study, and in the case of the Chinese sites the word count given in the table represents the number of words rather than characters. The English museum texts consist of visitor information from the Victoria & Albert Museum, the British Museum, National Museum of Scotland, Museum of London, and the Science Museum of London. The Chinese museum texts consist of visitor information from the Beijing Capital Museum, National Museum 8 of China, The Palace Museum, Shanghai Art Museum, and the China Science and Technology Museum. In order to ensure comparability, the corpora in this study only include the texts which function to provide instructions or general information to visitors – such as transportation, tickets, café, disabled access, shops, and do not include texts related to the content of exhibitions. After the webpages which meet the criteria of the selection are downloaded, the texts are converted to the format of plain texts and imported to the corpus software Paraconc, which allows the retrieval of data on the patterns of the texts, including the word frequency list. Group Words Victoria & Albert Beijing Capital Victoria & Albert Beijing Capital English Museum Chinese Museum Source Text Source Text Translated Text Translated Text Texts Texts (VAM-ST) (BCM-ST) (VAM-TT) (BCM-TT) (EMT) (CMT) 1,956 1,737 932 1,554 8,239 8,072 Table 2: Corpus compiled for the study This structure allows for analysis to take place in two distinct dimensions: literal and cultural (illustrated in Figure 1: Dimensions of Translation Analysis). Two-fold comparison between the versions of the Victoria and Albert Museum (VAM-ST and VAM-TT) and the versions of the Beijing Capital Museum (BCM-ST and BCM-TT) allows the data to be interrogated for literal accuracy in translation (represented by the light grey on Figure 1). Comparison between the Chinese version of the Beijing Capital Museum and the Chinese version of Victoria and Albert Museum (BCM-ST and VAM-TT) and the English version of the Victoria and Albert Museum and the English version of the Beijing Capital Museum (VAM-ST and BCM-TT) and more generally the English Museum Texts (EMT) with the Chinese Museum Texts (CMT) allows for the difference in the cultural dimension to be investigated (represented by the dark grey arrow on Figure1). These two levels of analysis allow us to investigate how accurate the literal translation is whilst also exploring if the cultural norms of the target community have been addressed. 9 Figure 1: Dimensions of Translation Analysis Analytical Approach: Genre Analysis As discussed above, our analytical approach is adopted from critical genre analysis (Bhatia 2004). Genre studies developed from focusing on the description of grammatical features or moves in texts, to exploring genre as “a powerful, ideologically active, and historically changing shaper of texts, meanings, and social actions” (Bawarshi and Reiff, 2010, p. 4). Genre analysis is therefore “multidimensional, multidisciplinary and multi-perspective” (Bhatia, 2004, p. 155), and divides the investigative analysis into three distinct stages, each focusing on a different space: 10 Textual Space: Lexico-grammatical features, rhetorical moves, discourse strategies, intertextuality, etc.; Socio-Cognitive (tactical and professional) Space: Correlation between text-internal and textexternal factors, participant relationships and the way they use the genre; Social Space: Social identities, social structures and the functioning of social institutions through discursive practices. Based on Bhatia’s (2004) model, our analytical approach (summarised in Table 3: Theoretical Framework used to investigate the websites) is: Textual Space: How are the visitors addressed, how the museum refers to itself, and what is the level of (in)formality? Socio-Cognitive Space: How does the text intend to influence the visitors? For example, argumentative texts or instructional texts have different communicative purposes, and create a different relationship with the readers. Social Space: Relationship between museum and society i.e. how is the role of museum reflected in the texts? For example, is it an entertainment site, a research organization, or a cultural centre and what experience are visitors expected to have in museums? Space Textual Socio-cognitive Social Illustration Features selected for investigation The lexical-grammar components 100 most frequent words, address terms, of the websites modal verbs The communicative goal of the Text type, non-verbal presentation of the website websites The social value of the museum Evaluative adjectives, extra-textual reflected in the website information Table 3: Theoretical framework used to investigate the websites This will allow us to examine both the accuracy and whether or not the translations deviate from or accommodate the genre convention of the original versions whilst allowing a cross-cultural comparison. 11 Results and Analysis The source text and the target text A comparison of the two sets of source texts and translations shows that the source text is generally relayed “accurately” (in the literal sense) without distortions, and the source texts also conform to the grammar of the target language. There are some translation shifts, but they are more likely to be conscious shifts rather than mistakes. For example, in the V&A website, the Chinese translation has a tendency to shift towards a more polite manner, by adding the honorific second person pronoun "您 nin" and politeness markers such as "请 qing" [please]. Example 1 illustrates the shifts. Example 1 (ST)Download PDF map of galleries layout and contents (in English). Maps are available at all entrance points to the museum. (TT) 请下载标注画廊布局与展览内容的 PDF 格式的电子地图(英文版). 您也可以在博物馆的任意 一个入口处获取纸质地图。 (BT) Please download PDF map with labels of galleries layout and exhibition content. You (in honorific form) can also request paper map at any entrances of the museum. In the Capital Museum of Beijing, there are also some consciously-made additions. For example, the following passage of the regulations is added on the top of the English page of the ticket service. Example 2 According to a Notice on Free Admission to Public Museums and Memorial Halls, Capital Museum has offered free admission to visitors since 28 March 2008. The Notice was jointly issued by the Department of Central Propaganda, Ministry of Finance, Ministry of Culture, and the State Administration Bureau for the Preservation of Cultural Heritage and Historical Relics. The reason why this passage is considered necessary in the English translation but not in the Chinese original is not known, but the addition presents the ticket service page in a more authoritative voice. Overall, as two of the leading museums in the UK and in China, the quality of their translations with regard to accuracy and the use of target languages is much better than those commented in previous studies (Kelly 1997, Sang 2011, Snell-Hornby 1999, for example). Whether accurate relay of the source text alone is the best strategy for the museum websites is now explored. 12 Genre conventions in English and Chinese museum websites The English and Chinese museum websites are examined in the three spaces in Bhatia’s (2004) model of critical genre analysis. Textual space In the textual space, the 100 most frequently occurring words in the English and Chinese museum websites were compared. Since both corpora are collected from visitor information in museum websites, it is not surprising to see common words in both corpora, such as museums, tickets, located, open, time, map, street, etc. Some differences between the two corpora are also expected due to the geographical location, so words like London occur frequently in the English corpus and Beijing or China are frequent in the Chinese corpus. However, further differences are found in the two corpora, which can be categorized broadly into two categories. First, differences can be seen in words related to interpersonal relationships – how visitors are addressed, or how museums refer to themselves. In the English museum websites, first person plural and second person pronouns (We, our, you, your) are on the 100 most frequent word lists. In the Chinese museums, only the honorific second person pronoun "您 nin" is on the list and with a much lower frequency than that of the second person pronoun in the English corpus. On the other hand, the word visitor is the fifth most frequent word in the Chinese corpus, but has a much lower frequency on the English list. This is because the Chinese museum websites often adopted a third person voice (e.g. Visitors can find information... as opposed to You can find ….). Besides the address terms, the Chinese museum websites also frequently use the obligatory modal verbs "勿 wu", meaning “not allowed to” and "需 xu", meaning “required to”, whereas in the English museum websites no such obligatory modal verbs are on the frequent list. Words that are on the English frequency lists but not on the Chinese ones (or with a much lower frequency) include disabled, café, cycle, accessibility, eating, etc. Words that are on the Chinese lists but not on the English frequency lists (or with a much lower frequency) include valid, identification document, reservation. Differences in lexical profiles of the websites can have implications in the sociocognitive and social spaces. 13 Socio-cognitive space In the social-cognitive space, the objective is to interpret the textual components as identified in the previous section and explore why the texts are constructed in such a way to achieve its communicative purpose. The English corpus uses more terms of address, in particular, frequent uses of second person pronouns to manage the relationship with the visitors. First person plural pronouns such as our collections, our galleries, and our café in reference to facilities in the museum also contribute to the personification of the institution. Other devices used to narrow the distance between the museum and the visitors include uses of cartoon illustrations, short sentences, and icons. Also, English museum websites all provide clear information on accessibility for different groups of visitors (disabled, family, children, etc.) which, although may be required by regulations, contribute to shortening the distance between museums and various groups of visitors. Based on these interpersonal features, it can be seen that the communicative aim of the English museum websites is to show that museums are visitor-friendly, and to make visitors feel that they are valued in this interaction. The Chinese museum websites tend to be more detached by adopting a third-person voice, or addressing visitors by honorific second person pronouns (indicating a formal relationship). This detached relationship between museums and visitors is further manifested by the forms of regulations commonly seen in the Chinese museum websites, which are not seen in the English museum websites. Example 3 is one article from the regulations of Capital Museum of Beijing. Example 3 五、酗酒者、衣冠不整者以及无行为能力或限制行为能力者无监护人陪伴的,谢绝入馆。 (Back translation) 5. Those under the influence of alcohol, improperly dressed, or those of limited mental capacity who are unaccompanied are not allowed entry. The presentation of these regulations with a detached voice gives the Chinese website an authoritative tone. The communicative goal of the Chinese museum websites is to provide clear guidelines or regulations to the visitors – make it explicit what they can, and more importantly, what they cannot do when they visit museums. The reason that the museum websites in China and in the UK have different communicative goals may be related to the function of the museums in their respective societies. 14 Social space The textual features and the communicative goals are closely related to the role of museum websites. What museums are expected to provide to the public, and what people usually come to a museum for, can have an impact on what is included in the museum websites. A simple yet revealing way to explore the difference between the concept of 'museum' in English and in Chinese is to compare dictionary definitions. The Oxford English dictionary defines a museum as “a building in which objects of historical, scientific, artistic, or cultural interest are stored and exhibited”, and other English dictionaries define the word in a similar way. The Xinhua Chinese dictionary defines the equivalence of museum "Bowuguan" as “征集、保藏、陈列和研究代表自然和人类的实物,并为公众提供知识、教育和欣赏的文化教育机 构” [a cultural educational organization which collects, stores, displays, and studies objects representing nature and humankinds, and which provides knowledge, education and aesthetics to the public.] Other studies on the development of Chinese museums similarly argue that they have a different function from Western museums (e.g. Du, 2006). These definitions indicate that the perceived role of the museum in Chinese and English cultures is different. Further evidence in the corpora supports this difference. The English websites tend to be more evaluative with frequent uses of positive adjectives, as commonly seen in advertisements. The strong promotional discourse in the museum website presents museums as commodities. The advertising discourse is most obvious in the museum shop. Example 5 Visit our acclaimed shops for a huge range of gifts, jewelry, books, textiles and stationery, celebrating the best of British design as well as wonderful finds from all over the world. ..Many items are exclusive to the V&A, commissioned from contemporary designers and makers and inspired by the museum’s collections and exhibitions. Since this is a webpage of the museum shop, it is not surprising to see these promotional linguistic features. On the other hand, the Chinese museums, perceived as cultural research centres, are much less explicit in selling souvenirs on the webpage of museum shops. Compared with the explicit persuasive features in the V&A website, the Capital Museum of Beijing website has the heading "文化商 品"[cultural products]. In this page, pictures of artefacts are presented, with only information of product names, prices, sizes, material, originality, and physical descriptions, no promotional linguistic features 15 are included. The website simply provides information but does not attempt to persuade visitors to buy the goods. Furthermore, information about cafés and restaurants included in all English museum websites are often absent in the Chinese museum websites. Overall, it can be concluded that the genre conventions in the English museum websites are interpersonal, serving the purpose of attracting visitors, and presenting the museum as a place for entertainment. On the other hand, the Chinese museum websites adopt an authoritative tone, serving the purpose of providing clear guidelines and regulations, and presenting the museum as a cultureeducation center. Translations and the target norms Finally, the effectiveness of the two translations is assessed by comparing them with their nontranslated counterparts. Although the English translation of the Capital Museum of Beijing stays close to its source text, it deviates greatly from the genre conventions in the English museum websites. The detached and authoritative voices and the instructional regulations may not be expected by English visitors of the Chinese museum, and the information on accessibility, cafes and souvenirs they commonly look for are absent. Similarly, the Chinese translation of the V&A Museum also relays the source text in a high degree of accuracy, but the explicit promotional discourse in the Chinese translation is not a norm commonly seen in Chinese museum websites. Step-by-step guidelines as to where to collect the tickets, how to collect tickets, what documents may be required commonly seen in the Chinese websites are also missing here. Assessing the quality of the translation only in relation to the source text assumes that the translation exists in a vacuum (with its only tie to the source text), and assumes that different language versions automatically lead to successful multilingual communication. However, users of translations draw from their experiences with similar types of texts in their target language to understand the translations, and therefore translations which deviate greatly from the norms of the target language may present challenges for the users and will not achieve the desired effect. 16 Discussion The results show that original language source texts are generally accurately translated with what Catford (1965) would define as equivalent words and correct grammar. This assumes symmetry between languages (Snell-Hornby 1988) which does not exist between English and Chinese, therefore the translated text may not fulfill the function of the original (Nord, 1991). Moreover, our analysis of translated museum texts and the norms of museum texts in the target language, suggests that equifuncational translation (Nord 1997) alone may not be the best strategy for websites. The equifunctional approach guides translators to focus on functional units in the source text, and to identify what function the source text intends to achieve. However, following Bhatia's (2004) model of genre, the functional units in a text need to be broken down into three spaces. Because the websites function differently in the social spaces of the two cultures, the functions to be achieved in textual cognitive and socio-cognitive spaces will require translation shifts. English and Chinese websites are both designed to attract and provide information to the visitors. This requires knowledge of cultural expectations of tourists i.e. the information tourists may expect to see and how this information is usually presented. Our corpus analysis suggests that because British museums are socially recognized as multipurpose centres which include retail, food and drink, their websites need to communicate in a relational style with their readers in the socio-cognitive space (Bhatia, 2004). This will be reflected in uses of certain lexico-grammatical items in the textual space, such as reference to leisure facilities (cafés and shops.), or promotional features. On the other hand, Chinese museums tend to be regarded as centres of high culture and education, their websites are presented in an instructional tone. Chinese users understand websites as a place to provide guidelines and regulations of entrance, ticket reservations and access to facilities. The lexical-grammatical items commonly featured in the Chinese website include impersonal address forms, many references to ticket reservations, and so on. The underpinning assumption within the tourism literature to date is that the source text is worthy of being translated in its entirety and that this will fulfill the expectations of the new reader. Our findings suggest that what is developed for use in the source language may be inappropriate for the translated language due to functional expectations, linguistic norms, cultural institutions, and other idiosyncrasies. 17 These will either render the content of the translation irrelevant or the tone of it inappropriate. The benefit of application of these theoretical issues to tourism is that the relationship between tourism consumption and translation is one mediated by culture. Tourism is in essence the explicit consumption of culture and translations that facilitate tourism activities must espouse an acknowledgement that the underpinning cultural sensibilities of the source inform its lexical content. Therefore, the underpinning sensibilities of the target language must form the basis upon which translation is conducted. The focus on cultural and lexical accuracy from the perspective of the source text only is most simply framed as a ‘red herring’, thus our call is for multiple spaces of interpretation to be considered prior to the source text even being engaged with. Conclusions It would be beneficial for translators to understand how texts function in the three different spaces, based on sensitivity to the target culture. The method we proposed to assess to what extent a piece of translation conforms to the target norms is collecting samples of texts produced for the same or similar purposes in the target language as the control group. The translator then begins by comparing the profile of lexical items in the translations and the control group. If some lexical items occur in a lower or higher frequency in the translations than in the control group, the translator can then explore the texts further to establish what the communicative purpose of these items is and whether these linguistic features are associated with particular values or perceptions in the society. Finally, translators need to make decisions whether and how to adopt the functions of the source text, so that the translation can most effectively achieve its aim in the target culture. As far as the tourism industry is concerned, we posit the question for consideration: what is accuracy in translation for tourism? Translation implicitly suggests accuracy of the lexical content of a source text. Many of the exchanges that take place in tourism do so at a cultural level however, an exchanges that are distinctly abstracted from the necessity for accurate lexical engagement. This notion permeates all stakeholder exchanges within the industry both between organizations and consumers, between organizations and within organizations. In a truly globalized industry it is imperative that cultural sensibilities take precedent over arbitrary notions of the need to be faithful to lexical content alone: if we are not able to connect cross-culturally then we are less effective in this business. Indeed, a Western 18 obsession with objective lexical accuracy perpetuates the apparent struggle that exists within the translation activities discussed here. Translation forms a vital tool in the inventory of the global tourism industry and it requires to be treated with the appropriate level of sensitivity rather than a predisposition for ‘accuracy’. The required form of translation does not readily subsist within the functional theory of translation (Table 1) as the translated text requires a cultural jump. Practically this means that the translator, or rather the website author, needs to enter the cultural mindset of the reader. Yes, they should include the pertinent information from the original website, however they may have to include other information required by the target culture. For example, an English adaptation of a Chinese website could tell the reader about the availability or otherwise of retail and refreshments, and attempt to build a relationship with the visitor. Whereas, a Chinese adaptation of a British website might only note that there are other facilities available and subsequently describe the different uses of the venue in the UK, which may help to put them at ease. References Allison, M. T., & Hibbler, D. K. (2004). Organizational barriers to inclusion: Perspectives from the recreation professional. Leisure Sciences, 26(3), 261-280. Bawarshi, A. S., & Reiff, M. J. (2010). Genre: An Introduction to History, Theory, Research, and Pedagogy. Indiana: Parlor Press and the WAC Clearinghouse. Bhatia, V. K. (2004). Worlds of Written Discourse. New York: Continuum. Bosseaux, C. (2004). Point of view in translation: a corpus-based study of French translations of Virginia Woolf's To The Lighthouse. Across Languages and Cultures, 5(1), 107-122. Bryce, D., MacLaren, A. C., & O'Gorman, K. D. (2013). Historicising hospitality and tourism consumption: Orientalist expectations of the Middle East. Consumption, Markets and Culture, DOI:10.1080/10253866.2012.662830. Buckley, R., Cater, C., Linsheng, Z., & Chen, T. (2008). Shengtai luyou: Cross-cultural comparison in ecotourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 35(4), 945-968. Butler, R., Curran, R., and O'Gorman, K. (2013) Pro Poor Tourism in a First World Urban Setting: Case study of Glasgow Govan. International Journal of Tourism Research. 15(5), 443-457. Catford, J. C. (1965). A Linguistic Theory of Translation. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Chen, J. S., & Hsu, C. H. C. (2000). Measurement of Korean tourists’ perceived images of overseas destinations. Journal of Travel Research, 38(4), 411-416. Du, S. (2006). 从博物馆的定义看中国博物馆的发展 [The implication of the definition of museum on the development of Chinese museums]. Jounral of Hebei University (philosophy and social science edition), 2006(6), 119-121. 19 Ghadessy, M., & Gao, Y. (2001). Small corpora and translation: comparing thematic organization in two languages. In M. Ghadessy, A. Henry & R. L. Roseberry (Eds.), Small Corpus Studies and ELT (pp. 335-362). Amsterdam: John Benjamins. Hatim, B., & Mason, I. (1990). Discourse and the Translator. London: Longman. Hatim, B., & Mason, I. (1997). The Translator as Communicator. London: Routledge. Ho, J. K. (2002). Multilingual e-business in a global economy: Case of SMEs in the lodging industry. Information Technology and Tourism, 5(1), 3-11. Hu, G. (2003). Translation as adpatation and selection. Perspectives: Studies in Translatology, 11(4), 283291. Hu, G. (2011). 生态翻译学的研究焦点与理论视角 [The research focus and theoretical perspective of eco-translatology]. Chinese Translators Journal, 32(2), 5-9. Hu, K., & Zhu, Y. (2008). 基于语料库的莎剧《哈姆雷特》汉译文本中显化现象及其动因研究 (A corpus-based study of explicitation and its motivation in two Chinese versions of Shakespeare's Hamlet). Foreign Languages Research 108(2), 72-80. Hunston, S. (2002). Corpora in Applied Linguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Jin, H. (2004). 全球语境下的旅游广告 [Toursim advertisment in a global context]. Shanghai Journal of Translators for Science and Technology, 2004(3), 51-54. Kelly, D. A. (1998). The translation of texts from the tourist sector: textual conventions, cultural distance and other constraints. TRANS: revista de traductología(2), 33-42. Kang, N. (2005). 从语篇功能看汉语旅游语篇的翻译 [The translation of Chinese tourism texts: from the perspective of the textual function]. Chinese Translators Journal, 26(3), 85-88. Kim, S. S., & Morrsion, A. M. (2005). Change of images of South Korea among foreign tourists after the 2002 FIFA World Cup. Tourism Management, 26(2), 233-247. Lam, T., Zhang, H., & Baum, T. (2001). An investigation of employees' job satisfaction: the case of hotels in Hong Kong. Tourism Management, 22(2), 157-165. Li, D., & Wang, K. (2009). 平行文本比较模式与旅游文本的英译 [The comparative model of parallel texts and the translation of tourism texts into English]. Chinese Translators Journal, 30(4), 54-58. Li, K. W., & Law, R. (2007). A novel English/Chinese information retrieval approach in hotel website searching. Tourism Management, 28(3), 777-787. Li, X. R., & Stepchenkova, S. (2011). Chinese Outbound Tourists’ Destination Image of America: Part I. Journal of Travel Research, 51(3), 250-266. Liu, X., & Li, H. (2008). 北京世界文化遗产人文景观介绍翻译研究 [Translation Studies on Introductions at World Cultural Heritage Sites in Beijing]. Beijing: Guangming academic series. Mason, I. (2004). Textual practices and audience design: an interactive view of the tourist brochure. In M. P. Navarro Errasti, R. L. Sanz Rosa & S. Murillo Ornat (Eds.), Pragmatics at Work: the Translation of Tourist Literature (pp. 157-176). Bern: Peter Lang. Mauranen, A., & Kujamäki, P. (2004). Translation Universals: Do they exist? . Amsterdam: John Benjamins. Munday, J. (1998). A computer-assisted approach to the analysis of translation shifts. META: Translator's Journal, 43(4), 542-556. Munday, J. (2008). Introducing Translation Studies: Theories and Applications. London: Routledge. Nord, C. (1991). Text Analysis in Translation. Theory, Method and Didactic Application of a Model for Translation-Oriented Text Analysis. Amsterdam: Rodopi. Nord, C. (1997.) Translation as a Purposeful Activity: Functionalist Approaches Explained. Manchester: St Jerome. Olohan, M., & Baker, M. (2000). Reporting that in translated English: Evidence for subconscious process of explicitation. Across Languages and Cultures, 1, 142-172. 20 Oppenheim, A. L. (1967). Letters from Mesopotamia: Official, business, and private letters on clay tablets from two millennia. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Prentice, R., & Andersen, V. (2007). Interpreting heritage essentialisms: Familiarity and felt history. Tourism Management, 28(3), 661-676. Pritchard, A., & Morgan, N. J. (2001). Culture, identity and tourism representation: marketing Cymru or Wales? Tourism Management, 22(2), 167-179. Ryan, C., & Gu, H. (2010). Constructionism and culture in research: Understandings of the fourth Buddhist Festival, Wutaishan, China. Tourism Management, 31(2), 167-178. Sang, L. (2011). 旅游景点名称翻译的原则与方法——以庐山等旅游景区为例 [The prinicple and method of translating names of scenic spots - an example of Lu mountain.] Chinese Science & Technology Translators Journal, 24(4): 46-49. Shuttleworth, M., & Cowie, M. (1997). Dictionary of Translation Studies. Manchester: St. Jerome. Sinclair, J. (2001). Preface. In M. Ghadessy, A. Henry & R. L. Roseberry (Eds.), Small Corpus Studies and ELT (pp. vi-xv). Amsterdam: John Benjamins. Snell-Hornby, M. (1988). Translation Studies: An integrated approach. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. Snell-Hornby, M. (1999). The 'ultimate confort': word, text and the translation of tourist brochures. In G. Anderman & M. Rogers (Eds.), Word, Text, Translation (pp. 95-103). Clevedon: Multilingual Matters. Wang, A. (2012). 入乎其内,出乎其外 - 论汉英旅游翻译过程中思维的转换与重写 [A study of the cognitive process and rewriting in Chinese-English tourism translation]. Chinese Translators Journal, 33(1), 98-102. Wang, W. (2003). 英汉语言对比与翻译 [Contrastive Studies of Chinese and English and Translation]. Beijing: Beijing University Press. Wu, Y. (2004). 旅游翻译的变异理论 [The strategy of adapataion in tourism translation]. Shanghai Journal of Translators for Science and Technology, 2004(4), 21-24. Xiong, L., & Liu, H. (2011). 旅游网页文本的编译策略 [The editing strategy in translation of tourism websites]. Chinese Translators Journal, 32(6), 63-67. Yang, J., Ryan, C., & Zhang, L. (2012). The use of questionnaires in Chinese tourism research. Annals of Tourism Research, 39(3), 1690-1693. Yang, D. (2009). 对贵州非物质文化遗产外宣翻译的一些思考 [Rethinking the translation for international communication on intangible cultural heritage in Guizhou]. Journal of Guizhou Study, 2009(6), 117-119. Ye, M. (2008). 旅游宾馆介绍语篇的语用分析及其翻译 [A pragmatic analysis of introductory texts of hotels and their translation]. Chinese Translators Journal, 29(4), 78-83. Zhang, G. (1999). 生态旅游的理论与实践 [Theories and practices of ecotourism]. 旅游学刊 [Journal of Tourism], 1999 (1): 51-55. Zhang, M. (2005). 翻译研究的功能途径 [Functional Approaches to Translation Studies]. Shanghai: Shanghai Foreign Language Education Press. Zeng, B., & Ryan, C. (2012). Assisting the poor in China through tourism development: A review of research. Tourism Management, 33(4), 239-248. 21