Organizing Mega-projects: Understanding their Cultural Practices

advertisement

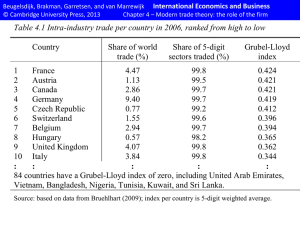

Organizing Mega-projects: Understanding their Cultural Practices Alfons van Marrewijk Prof. Dr.ing. Alfons van Marrewijk Professor in Business Anthropology Department Organization Sciences Faculty of Social Sciences VU University Amsterdam De Boelelaan 1081 1081 HV Amsterdam The Netherlands +31 (0)20 598 7640 (Secretariat) fax +31 (0)20 598 6765 a.h.van.marrewijk@vu.nl Paper to be presented at 1st workshop: Megaprojects: Theory meets Practice 12-13 September, London 1 Introduction Complex and extensive civil engineering and construction mega-projects frequently attract societal attention. Newspaper headlines, journalistic books, TV specials, and parliamentary inquiries inform the public about nuisances, failures, budget overruns, time delays, citizen resistance, and resigning politicians. Mega-projects rarely remain uncontested, particularly if pursued within a democratic political context, as they are perceived not only as costly, but also as significant threats to local quality of life. For example, the construction of a new Mexican airport (Dewey and Davis, 2013) and the extension of the Stockholm rail (Corvellec, 2001) never came to execution due to citizen resistance. In another example, the revalorization of the Stuttgart 21 railway station undermined important policy objectives such as historic preservation, environmental protection and primarily benefited already affluent individuals and groups (Novy and Peters, 2012). Therefore, Flyvbjerg et al. (2003) call mega infrastructure projects ‘political and physical animals’. Not withstanding their contested nature, there has been a sharp increase in the magnitude and frequency of major infrastructure projects (Flyvbjerg et al., 2003). Mega-project organizations have become popular by public politicians and local officials to create attractive, sustainable and economically viable urban areas for citizens (Lehrer and Laidley, 2008;Diaz Orueta and Fainstein, 2008). Such projects have become great symbols of modern engineering and for politicians an important political legacy; highly visible, material results of public policy and officials at the local and national level (Del Cerro Santamarıa, 2013a;Trapenberger Fick, 2008). Although mega-projects have become important to politicians and civilians, for a long time academic attention was reserved to the engineering discipline (Cicmil and Hodgson, 2006a;Morris, 2011). With its intellectual roots in engineering science, project management research has traditionally been concerned with planning techniques, methods and tools for optimizing project performance, and project efficiency (Söderlund, 2004). Studies on megaprojects primarily focused upon quantitative evaluations of the performance of mega-projects (Merrow, McDonnell and Arguden, 1988) (Flyvbjerg et al., 2003), the public private collaboration in mega-projects (Koppenjan, 2005), the management of mega projects (Hertogh, Baker, Staal-Ong and Westerveld, 2008), and lessons learned on risk and management of mega- 2 projects (Greiman, 2013). By now we have learned that the phenomenon of mega-projects have increasingly attracted attention, but what exactly is the nature of mega-projects? Defining mega-projects Although mega-projects have been constructed ever since the pyramids of Egypt, the Maya cities in Mexico and the road networks of the Roman Empire, mega-project were first conceptualized in the early 1970’s with the Canadian government and the American contractor Bechtel simultaneously to describe large scale projects (Merrow et al., 1988). The word ‘mega’ originates from the Greek word ‘mega’ and is a prefix or root word that can be combined with other words. In the Oxford Advanced Learners Dictionary (1990) ‘mega’ is connected to the number of one million (e.g. megabyte, megacycle). Furthermore, it is synonym for very large or great (e.g. megaphone) and used for things that are extra ordinary examples of their kind (e.g. megastar). While ‘magna’ signifies large and great in spiritual sense, ‘mega’, ‘megal’, ‘megalia’ and ‘megalo’ are all referring to large, big, full-grown, vast, high in material sense (e.g. megaliths). Connecting the word ‘mega’ to ‘project’ emphasizes the uniqueness as well as the greatness and largeness in material sense of the project. Finally, in the International Systems of Units ‘mega’ is opposed to ‘micro’. Therefore, a micro perspective of organizing practices in mega-projects is a nice paradox to solve in this book. A book on mega-projects should discuss the question to what extend mega-project are different from other projects? This question is not easy to answer as mega-projects and other projects both differ from any other form of organizing in their intended temporality and their death (Söderlund, 2013). They share the general nature of a project, which is in traditional literature on project management, perceived to be a temporary aggregation of stakeholders working together to get something delivered within time, scope and budget (Söderlund, 2004). Interestingly, developing countries did not do better or worse than developed countries in executing mega-projects (Merrow et al., 1988). Mega-project can be defined as simply as projects whose capital for the complete construction exceeds a certain number of million US dollar (Merrow et al., 1988). Or can be defined as complex as Del Cerro Santamaria (2013a: xxiv), who perceives megaprojects in an urban context as large-scale development projects that sometimes have an iconic design component, that usually aim at transforming or have the potential to transform a city’s or parts of 3 a city’s image, and are often promoted and perceived by the urban elite as crucial catalysts for growth and even as linkages to the larger world economy. According to Williams (2002) complex mega-projects distinguishes themselves from other projects in their structural complexity, which is the interaction and interdependency of elements in a project, and uncertainty, resulting from a lack of clearness and agreement over project goals and the way these goals have to be research. An analysis of a rather limited set of literature on mega-projects (Hertogh et al., 2008;Van Marrewijk, Clegg, Pitsis and Veenswijk, 2008;Flyvbjerg et al., 2003;Merrow et al., 1988;Williams, 2002;Pryke and Smyth, 2006) results in a number of characteristics of megaprojects; high degree of complexity; large-scale, and geographical dispersed; enormous budgets (over billions of euros); have a major impact on the environment and society; can be subject of citizen resistance; the period of inception until realization often covers decades; embedded in a national political context which can change over time; new and unproven technologies and legislation; involvement of many stakeholders; often unique at national level; high quality aesthetics; incorporate many uncertainties; mixture of joint organization and sub-contracting to legally separate partners; Old versus new mega-projects Leher and Laidley (2008) make a distinction between ‘old’ and ‘new’ mega-projects in the development of urban economies. In the “great mega-project era” of the 1950s and 1960s (Altshuler & Luberoff, 2003) mega-projects were the monolithic constructions with little attention for draagvlak, citizen participation and environmental issues. Since then mega-projects have evolved (Fainstein, 2008). The ‘new’ mega-projects take the form of vast complexes characterized by a mix of uses, a variety of financing techniques, and a combination of public4 and private-sector initiators (Lehrer and Laidley, 2008). The construction of new transport infrastructures, or the extension of existing ones, and complex building projects are examples of these new mega-projects (Diaz Orueta and Fainstein, 2008). They involve a transformation of urban space, its built form and its specific land use(s) and changes the social practices in these urban landscapes (Van Marrewijk and Yanow, 2010;Lehrer and Laidley, 2008;Del Cerro Santamarıa, 2013b). Importantly, new mega-projects are often undertaken by state actors operating in collaboration with private interests in the pursuit of gentrification of city-regions within a competitive global system (Lehrer and Laidley, 2008;Del Cerro Santamarıa, 2013a: xxx). A study of 13 large-scale urban development projects in 12 European Union countries urban development projects showed that mega-projects are almost all state led and often state financed (Moulaert, Rodriguez and Swyngedouw, 2003: 250). Contractually however, these megaprojects are often defined in terms of Public Private Partnerships (PPP), in which there is a structural cooperation between public and private parties to deliver some agreed outcome (Van Marrewijk et al., 2008;Koppenjan, 2005). While these contractual arrangements therefore seek to address the many interests, which are at stake in complex mega-projects, they do not fully capture the complexity of the multiple, fragmented subcultures at work (Van Marrewijk et al., 2008). Problematic organizing of mega-projects The increasing complexity of new mega-projects attracted the attention of organization scholars (Bresnen, Goussevskaia and Swan, 2005). By the 1990’s project management had begun to attract serious attention of business and management researchers who became engaged in the development of project management as an scientific knowledge domain (Cicmil and Hodgson, 2006a). These academics, coming from sociology, business administration, psychology, and anthropology, brought in organization perspectives in which (mega)projects are perceived as temporal, organizational and social arrangements that should be studied in their context, culture, conceptions and relevance (Kreiner, 1995;Packendorff, 1995;Lundin and Söderlund, 1995). The dominant perception of organizing megaprojects as technical defined matters in demarked spatial settings with a particular kind of complex tasks that has to be solved is highly problematic (Kreiner, 1995;Söderlund, 2013;Engwall, 2003). 5 Mega-projects can’t be delivered with closed management systems as they are politicallysensitive and involving a large number of partners, interest groups, citizen opposition and other stakeholders (Hodgson and Cicmil, 2006;Bresnen et al., 2005). Therefore, explicit attention is needed to context as an interpretive framework for the environment(s) of organizational actors in mega-projects. It concerns the specific aspects and circumstances such as history, ideology, fields of action and technical infrastructures, within which cultural patterns are developed and reproduced, which drive or legitimize an assignation of meaning (Van Marrewijk et al., 2008). Context is important as humans manifest an immense flexibility in their response to the environmental forces they encounter, enact and transform (Geertz, 1973). In literature on mega-projects, power, politics and conflicting and opposing interests are generally excluded (Clegg and Kreiner, 2013;Hodgson and Cicmil, 2006). An exception is Flybjerg et al. (2003) who suggest that a main cause of overruns is a lack of realism in initial cost estimates, motivated by vested interests of partners. However, according to Clegg and Kreiner (2013) power in mega-projects has to be understood as relational effects, not as sources that can be held by partners. Project design, including contractual arrangements, and project cultures play a role in determining how managers and partners cooperate to achieve project objectives to a greater or lesser extent (Van Marrewijk et al., 2008). Therefore, Cicmil and Hodgson (2006b), suggest a more critical approach to understand the management of projects by exploring how the relationships between individuals and the project organization are produced and reproduced, how power relations create and sustain social relations. In sum, project management is a way of exercising power as projects are organizational entities constructed of relations of power (Clegg and Kreiner, 2013). To deal with relations of power, mega-project implementers have learned to expect and respect citizen opposition, and increasingly adapt their interventions and their decision-making processes to preempt or defuse claims against their proposals (Dewey and Davis, 2013: 17;Diaz Orueta and Fainstein, 2008). Planners and politicians adopted “everyone gains” rhetoric of both economic competitiveness and environmental sustainability and the paradigm of “do no harm” which is the idea that mega-projects should only proceed if their negative side effects are negligible, or significantly mitigated (Alsheudler and Luberooff, 2003;Lehrer and Laidley, 2008). These experiences have forced project implementers that planning legitimacy, implementation and sustainability of decisions depends also on the careful execution of a 6 collaborative process that is deemed fair and open to affected citizens (Innes and Booher, 2010). In line with this, Merrow et.al. (1988) come to the conclusion that cultural, linguistic, legal and political factors should be included in the organizing of mega-projects. Therefore, they advise the training of project managers to become aware of both institutional environment and internal project organization. The soft side of mega-projects Increasingly, academic attention is pushed towards issues of social interaction, power issues, reproduction, sense-making, and organizational culture (Van Marrewijk et al., 2008). Söderlund (2004) names this the ‘soft’ side of project management. He claims the need to combine the ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ side of project management to address the complexities of real projects (Söderlund, 2013). In line with this claim, a special issue of IJPM on managing construction mega-projects stresses to include, besides the technical and managerial aspects, also the social aspects of complexity in mega-projects (Li and Guo, 2011). The importance of ‘people issues’ is also acknowledged in the incorporation of so called ‘best practices’ in well established cultural practices in projects (Winter, Smith, Morris and Cicmil, 2006). From my own personal experience, Dutch managers of building and civil infrastructure mega-projects recognize the importance of a ‘people’ or ‘soft’ perspective on project management. And although I’m very sympathetic to the appeal for more attention to soft aspects in mega-projects, the separation of the ‘social’ and ‘natural’ world itself is an act of social construction (Latour, 2005). Latour (2005) argues that humans and objects have been established as two irrevocably sundered realms of knowledge and experience. From his perspective, this separation imposes a binary division on the world of human experience that is not itself in the world (Latour, 1993). In the same line, Orlikowski (2007: 1438) remarks to give up on treating the social and the technical as distinct and largely independent spheres of organisational life. As a trained engineer and academic anthropologist, I’m very sympathetic to this view when studying mega-projects. A way of making the world of people and the world of material phenomena equally problematic, as well as their intersections and entanglements in social-material hybrids Latour (1993) introduced the concept of symmetric anthropology. In this view mega-project are proliferating entities that are made and remade as mixes of the social and the material (Van Marrewijk and Yanow, 2010). 7 Mega-projects as a cultural phenomenon Ultimately, the theoretical debate above leads us to position mega-projects to be as much the object and outcome of social interactions as any other form of organizing within a multiple context of socially interdependent networks. Mega-projects bring together, under various contractual arrangements, differing and competing partners, interests, values and modes of rationality (ways of doing and thinking). The flux of everyday experience in projects is what provides the initial source of material for our speculative conjecturing (Chia, 2013: 35). Such an approach of mega-projects takes humans central and perceives mega-projects as social networks of people in the process of organizing (Van Marrewijk, 2007;Van Marrewijk and Veenswijk, 2006). Within the field of project management studies, attention for a cultural perspective on project management has increased significantly (Henrie and Sousa-Poza, 2005). However, the integrative perspective (Martin, 2002) used in many project management studies (Kendra and Taplin, 2004;Winch, Millar and Clifton, 1997) is too limited to fully understand culture practices in mega-projects. This definition states that culture is the totality of socially transmitted behaviour patterns, arts, beliefs, institutions, and all other products of human work and thought (PMI, 2000). In this definition there is no recognition of ambiguity, subcultures, power, and the decision-making practices of project managers and partners, who work within limited boundaries of rational behaviour (Alvesson, 1993;Alvesson, 2002). While different perspectives on organisational culture are well-documented in the literature (Smircich, 1983) the interpretative approach recognises that ambiguities, subcultures, conflicts and power and where applicable, various national, professional and project cultures, coexist and operate within mega-projects. In this approach, project culture is defined as the result of socially construction by project actors ascribing meaning to their situation, which together makes up a cultural framework, and through processes of interaction, meanings are created and reproduced. (Van Marrewijk and Veenswijk, 2006). It takes mega-projects not having a culture but as a culture. It is acknowledged that “to our despair mega-projects often develop lives of their own and their lives sometimes defy control by us mere mortals” (Engesson 1982 quoted in Merrow et al., 1988: 1). Such an interpretative perspective focuses at processes of meaning, sense making and social construction of culture by actors and come to a ‘verstehen’ of the constructed social reality 8 (Czarniawska, 1992). This learns us that (mega)project cultures consist of multiple fragmented subcultures (Kendra and Taplin, 2004), which can be used strategically for internal and external power struggles (Van Marrewijk, 2010). By examining these multiple rationalities and subcultures, rather than seeing them as having a singular, shared rationality per se or a single integrative culture, an alternative view is offered to Flyvbjerg et al.’s who claim that megaprojects are motivated by vested interests (Van Marrewijk et al., 2008). Based upon a rich personal experience in the field of mega-projects and a, rather limited, analysis of organization cultural literature (Van Marrewijk and Veenswijk, 2006;Martin, 2002;Alvesson, 2002;Czarniawska, 1992) the following cultural themes for the understanding of mega-projects are extracted (see table 1). Mega-project as culture Cultural themes Topics Cultural differences National cultures Organizational cultures Professional cultures Heterogeneity Large diversity of partners Local representations Transition rituals Collaboration Hybrid practices Power relations Project team dynamics Management style Knowledge sharing strategies Narratives and discourse Political discourses Project narratives Stories and myths Spatial settings Lay out project offices Distribution of project offices Material tools Tabel 1. Mega-projects as cultural phenomena 9 Understanding the mega-project as cultural phenomena through a practice based lens This introduction results in the claim for an in-depth understanding of cultural processes in mega-projects through the observation of everyday practices. Practices are the cultural manifestations and representations of the project as cultural phenomenon (Geertz 1973). Cultural practices are viewed a dynamic, on going, everyday actions that represent the ontological primacy of practice as fundamental to produce social reality (Feldman and Orlikowski, 2011). Such an understanding of cultural practices in mega-projects connects, what Söderlund (2013), calls the ‘micro’ and ‘macro’ project management. Micro project management is directed to the investigation of practices, rituals, and everyday routines while macro project management is related to societal aspects of projects, antecedents and consequences of projectification and firmlevel issues. The project-as-practice approach evolved as a critique on research that treats projects normatively, with no regard to their context or social setting, (Hällgren and Söderholm, 2011;Blomquist, Hällgren, Nilsson and Söderholm, 2010). This approach focuses at project activities and how actors make sense of these in project organizations (Blomquist et al., 2010). With a special attention to power, politics and the micro-activities and their meaning in the specific social setting the approach gives us insight in the everyday life of how different project actors, public and private, and citizen are involved in the process of co-creation mega-projects (Smits and Van Marrewijk, 2012). Following Nicolini et al. (2003) practices are perceived as dynamic and provisional, as activities that require some form of participation. In line with this, Geiger (2009) recognizes that practicing is not an individual cognitive resource, but rather something that people do together. Moreover, he verifies that practicing is a process of continuous enactment, refinement, reproduction and change based on tacitly shared understandings within the practicing community. For example, the ‘ritualization’ of project phase transitions and milestones facilitate and mediate the mega-projects process by providing a temporal and spatial platforms in which constructors, project actors, and interest groups are closely intertwined with power relations and political and economic interests (Ende and Marrewijk, 2013). As practices are a bricolage of material, mental, social and cultural resources (Nicolini et al., 2003), resistance is something 10 which is not grounded within the individual, but as distributed across actors and artifacts (Harty and Whyte, 2010). References Alsheudler, A. and D. Luberooff (2003). Megaprojects. The changing politics of Urban Public Investiments, Brookings Institutions, Washington. Alvesson, M. (1993). Cultural Perspectives on Organizations, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. Alvesson, M. (2002). Understanding Organization Culture, Sage, London. Blomquist, T., M. Hällgren, A. Nilsson and A. Söderholm (2010). 'Project-as-Practice: In Search of Project Management Research That Matters', Project Management Journal, 42, pp. 516. Bresnen, M., A. Goussevskaia and J. Swan (2005). 'Managing projects as complex social settings', Building Research and Information, 33, pp. 487-493. Chia, R. (2013). 'Paradigms and Perspectives in Organizational Project Management Research: Implications and Knowledge-Creation'. In: N. Drouin, R. Müller and S. Sankaran (eds.), Novel approaches to organizational project management research: translational and transformational. pp. 33-56. Copenhagen: Copenhagen Business School Press. Cicmil, S. and D. Hodgson (2006a). 'New possibilities of project management theory: a critical engagement', Project Management Journal, 37, pp. 111-122. Cicmil, S. and D. E. Hodgson (2006b). 'Critical research in project management. An introduction. '. In: D. E. Hodgson and S. Cicmil (eds.), Making Projects Critical. pp. 128. New York: Palgrave McMillan. Clegg, S. R. and K. Kreiner (2013). 'Power and Politics in Construction Projects'. In: N. Drouin, R. Muller and S. Sankaran (eds.), Novel approaches to organizational project management research. Translational and transformational. pp. 268-293. Copenhagen: Copenhagen Business School Press. Corvellec, H. e. (2001). 'Talks on Tracks - Debating Urban Infrastructure Projects', Studies in Cultures, Organizations and Societies, 7, pp. 25-53. 11 Czarniawska, B. (1992). Exploring Complex Organizations. A Cultural Perspective, Sage, London. Del Cerro Santamarıa, G. (2013a). 'Introduction'. In: G. del Cerro Santamarı ́a (ed.) Urban pp. xix - xlix. London: Emerald. Del Cerro Santamarıa, G. (2013b). 'Urban Megaprojects: A Worldwide View'. Research in Urban Sociology. Dewey, O. F. and D. E. Davis (2013). 'Planning, politics and urban mega-projects in developmental context: lessons from mexico city's airport controversy', JOURNAL OF URBAN AFFAIRS, 00, pp. 1–21. Diaz Orueta, F. and S. S. Fainstein (2008). 'The New Mega-Projects: Genesis and Impacts', International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 32, pp. 759–767. Ende, L. v. d. and A. H. v. Marrewijk (2013). 'Transition Rituals in Construction Megaprojects'. EGOS 2013. Montreal. Engwall, M. (2003). 'No project is an island: linking projects to history and context', Research Policy, 32, pp. 789-808. Fainstein, S. S. (2008). 'Mega-projects in New York, London and Amsterdam', International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 32, pp. 768–785. Feldman, M. S. and W. Orlikowski (2011). 'Theorizing Practice and Practicing Theory', Organization Science, 32, pp. 789-808. Flyvbjerg, B., N. Bruzelius and W. Rothengatter (2003). Megaprojects and Risk. An Anatomy of Ambition, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. Geertz, C. (1973). The interpretation of cultures, Fontana Press, London. Geiger, D. (2009). 'Revisiting the Concept of Practice: Towards an Argumentative Understanding of Practising', Management Learning, 40, pp. 129-144. Greiman, V. A. (2013). Mega Project Management. Lessons on Risk and Project Management from the Big Dig., Wiley/PMI. Hällgren, M. and A. Söderholm (2011). 'Projects-as-Practice'. In: P. W. G. Morris, J. K. Pinto and J. Söderlund (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Project Management. pp. 500-518. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 12 Harty, C. and J. Whyte (2010). 'Emerging hybrid practices in construction design work: the role of mixed media', ASCE Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 136, pp. 468-476. Henrie, M. and A. Sousa-Poza (2005). 'Project Management: a Cultural Review', Project Management Institute, 36, pp. 5-14. Hertogh, M., S. Baker, P. L. Staal-Ong and E. Westerveld (2008). Managing Large Infrastructure Projects.Research on Best Practices and Lessons Learnt in Large Infrastructure Projects in Europe, AT Osborne. Hodgson, D. E. and S. Cicmil (2006). 'Making Projects Critical'. New York: Palgrave McMillan. Innes, J. E. and D. E. Booher (2010). Planning with complexity: An introduction to collaborative rationality for public policy, Routledge, New York. Kendra, K. and T. Taplin (2004). 'Project Success: A Cultural Framework', Project Management Journal, 35, pp. 30-45. Koppenjan, J. (2005). 'The Formation of Public-Private Partnerships: Lessons from Nine Transport Infrastructure Projects in the Netherlands', Public Administration, 83, pp. 135157. Kreiner, K. (1995). 'In search of relevance: project management in drifting environments', Scandinavian Journal of Management, 11, pp. 335-346. Latour, B. (1993). We have never been modern Harvester Wheatsheaf, London. Latour, B. (2005). Reassembling the social: an introduction to actor-network theory, Oxford University Press, Oxford. Lehrer, U. and J. Laidley (2008). 'Old Mega-Projects Newly Packaged? Waterfront Redevelopment in Toronto', International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 32, pp. 786–803. Li, H. and H. L. Guo (2011). 'International Journal of Project Management special issue on “Complexities in managing mega construction projects”', International Journal of Project Management, 29, pp. 795-796. Lundin, R. A. and J. Söderlund (1995). 'A theory of the temporary organization', Scandinavian Journal of Management, 11, pp. 437-455. Martin, J. (2002). Organizational culture : mapping the terrain, Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, Calif., etc. 13 Merrow, E. W., L. M. McDonnell and R. Y. Arguden (1988). 'Understanding the outcome of mega-projects. A quantitative analyse of very large civilian projects'. Rand Reports. Morris, P. W. G. (2011). 'A brief histroy of project management'. In: P. W. G. Morris, J. K. Pinto and J. Söderlund (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Project Management. pp. 15-36. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Moulaert, F., A. Rodriguez and E. Swyngedouw (2003). 'The Globalized City: Economic Restructuring and Social Polarizationi in European Cities'. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Nicolini, D., S. Gherardi and D. Yanow (2003). Knowing in Organizations. A Practice-Based Approach, M. E. Sharpe, London. Novy, J. and D. Peters (2012). 'Railway station megaprojects as public controversies. The case of Stuttgart 21', Buildt Environment, 38, pp. 128-145. Packendorff, J. (1995). 'Inquiring into the temporary organization: new directions for project management research', Scandinavian Journal of Management, 11, p. 319 333. PMI (2000). A guide to the project management body of knowledge. PMBOK guide., Newtown Square: PA. Pryke, S. and H. Smyth (2006). 'The Management of Complex Projects'. Oxford: Blackwell. Smircich, L. (1983). 'Concepts of Culture and Organization Analysis', Administrative Science Quarterly, 28, pp. 339-358. Smits, K. and A. H. Van Marrewijk (2012). 'Chaperoning: Practices of Collaboration in the Panama Canal Expansion Program', Chaperoning: Practices of Collaboration in the Panama Canal Expansion Program, 5, pp. 440-456. Söderlund, J. (2004). 'Building theories of project management; past research, questions for the future', International Journal of Project Management, 22, pp. 183-191. Söderlund, J. (2013). 'Pluralistic and processual understanding of projects and project organizating; towards theories of project temporality'. In: N. Drouin, R. Muller and S. Sankaran (eds.), Novel Approaches to organizational project management research. Translational and transformational. pp. 117-136. Copenhagen: Copenhagen Business School Press. Trapenberger Fick (2008). 'The cost of the technological sublime: daring ingenuity and the new San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge'. In: H. Priemus, B. Flyvbjerg and B. van Wee (eds.), 14 Decision-making on mega projects: cost-benefit analysis, planning and innovation. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar. Van Marrewijk, A. H. (2007). 'Managing project culture: The case of Environ Megaproject', International Journal of Project Management, 25, pp. 290-299. Van Marrewijk, A. H. (2010). 'Situational Construction of Dutch – Indian Cultural Differences in Global IT Projects ', Scandinavian Journal of Management, 26, pp. 368-381. Van Marrewijk, A. H., S. Clegg, T. Pitsis and M. Veenswijk (2008). 'Managing Public-Private Megaprojects: Paradoxes, Complexity and Project Design', International Journal of Project Management, 26, pp. 591-600. Van Marrewijk, A. H. and M. Veenswijk (2006). The Culture of Project Management. Understanding Daily Life in Complex Megaprojects, Prentice Hall Publishers / Financial Times, London. Van Marrewijk, A. H. and D. Yanow (2010). 'Organizational Spaces. Rematerializing the Workaday World'. p. 218. Northampton: Edward Elgar. Williams, T. (2002). Modelling Complex Projects, Blackwell, London. Winch, G., C. Millar and N. Clifton (1997). 'Culture and Organization: The Case of Transmanche-Link', British Journal of Management, 8, pp. 237-249. Winter, M., C. Smith, P. Morris and S. Cicmil (2006). 'Directions for future research in project management: The main findings of a UK government-funded research network', International Journal of Project Management, 24, pp. 638-649. 15