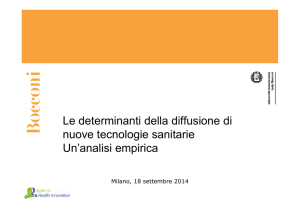

The Organization as a Filter of Institutional Diffusion

advertisement