Transfer of Learning

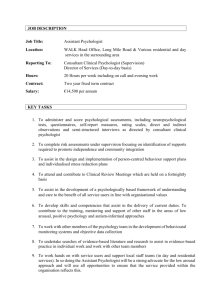

advertisement

Transfer of Learning: Reflections on the foundations of the phenomenon from educational psychology Transfer of Learning: Reflections on the foundations of the phenomenon from educational psychology John E. Wisneski Indiana University Bloomington 1 Transfer of Learning: Reflections on the foundations of the phenomenon from educational psychology 2 Introduction This whitepaper is intended to summarize the theoretical foundations of the current literature on the transfer of learning, with particular focus on the phenomenon’s educational psychology roots, and provide a personal reflection based on the author’s experiences in the management consulting profession. After describing the different types of transfer cited in the literature, the process of transfer is explored in greater detail, with particular focus on both the classical approaches and the evolution of contemporary frameworks which illuminate the phenomenon. A characterization of the research settings in which the phenomenon has been studied is offered, and both the predictors and barriers of successful transfer are discussed. Taxonomy of Transfer Broadly speaking, transfer is defined as the ability to extend what has been learned in one context to new contexts. With respect to instruction, a key assumption by instructional designers is that their students will be able to transfer the skills learned in a training setting and apply them to problems in different settings. The literature on transfer in education began in earnest at the turn of the century. One of the earliest studies on the transfer of learning was conducted by Woodworth & Thorndike (1901). Through testing the identification of specific characters in written words, the authors conceptualized a behaviorist approach to transfer and found that newly acquired skills are most likely to increase the speed but not necessarily the accuracy of the application of these skills in new contexts. Subsequent research has explored the nuance of the phenomenon, resulting in the emergence of taxonomy by transfer type. In the broadest sense, routine transfer refers to a simple pattern of learn-it-here, apply-it-there (Perkins & Salomon, 2012). Routine transfer, also referred to as “low-road” transfer, is spontaneous application of highly practices skills, with little need for reflective thinking. Transfer situations can also be Transfer of Learning: Reflections on the foundations of the phenomenon from educational psychology 3 opportunities for invention and reorganization, however, and are not confined to simply carrying forward and applying the same knowledge (Lobato, 2012). Adaptive transfer, or “high road” transfer, involves not just routine application of knowledge and skills in a new context, but rather suggests adapting and revising prior knowledge in the context of the transfer (Schwartz, Chase & Bransford 2012). While adaptive transfer implies an efficient way to apply new skills in knowledge in multiple contexts, these authors also caution against a term they call overzealous transfer (OZT), where the learner focuses primarily on seeing the old in the new because old routines have been successful before. It is argued that OZT can hinder innovation, and may lead to an obfuscation of nuance in a new context that may render the transfer useless. In much the same way that adjustments may be made in the destination context, backward transfer refers to the phenomenon where dealing with the new situation may in fact lead to revisions in a prior conception. The process of transfer can also be the result of the movement of knowledge within the organization that yields an exemplar performance. In most organizations, best practice transfer refers to the application of a relevant example that produces results better than any known alternative (Szulanski, 2002). Finally, negative transfer is the learning of irrelevant information due to the use of misappropriated prior knowledge in a new context (Clark & Voogel, 1985). An example of negative transfer may be the inappropriate application of grammar rules from one language to the next by foreign language students. The Process of Transfer In addition to the type of transfer, Royer (1979) has suggested that the extent of transfer is a continuous construct. Near transfer implies a similarity to the training setting, whereas far transfer requires generalizability in contexts that are very different from the training Transfer of Learning: Reflections on the foundations of the phenomenon from educational psychology 4 environment. As Clark & Voogel (1985) point out, most instructional design models tend to focus on near transfer of procedural knowledge. Classical Approaches to Transfer The literature has centered on both behaviorist and cognitive approaches to transfer. Woodworth & Thorndike (1901) provided the earliest empirical support of the behaviorist approach, which posits that transfer occurs when application contexts are identical. Behavioral models typically include: a) a procedural objective, b) direct instruction, c) practice, and d) corrective feedback and reinforcement (Clark & Voogel, 1985). Criticism of this approach centers on the perceived limitation that identical element training is only capable of near transfer (Bransford, 1979). Cognitive approaches, on the other hand, assume that instruction is processed and modified by students’ thought. These instructional models rely on a) encouraging discovery, b) suggesting the use of previously acquired knowledge through analogy or advance organizers, and c) testing of the generalizability of the learning. While scholars claim cognitive approaches increase the applicable “distance” of transfer (Nitsch, 1977; Rumelhart & Norman, 1981), they also grant the necessity of the learner to draw the appropriate analogies from previous knowledge to support their learning. Cognitive approaches also rely on feedback, and as Mathan & Koedinger (2005) point out, “jobs today require not only ready-made expertise for dealing with known problems, but also intelligence to address novel situations” (page 257). These authors suggest the challenge for instructional designers is to focus student feedback on models of desired performance. Extending beyond the two major approaches to transfer of learning, these classical definitions each rely on a series of four mechanisms that collectively make-up the process of transfer. The first of these mechanisms, identical rules, was first conceptualized by Woodworth & Thorndike (1901) as the identification of overlapping production rules between two discrete tasks. Although Transfer of Learning: Reflections on the foundations of the phenomenon from educational psychology 5 this mechanism can account for transfer in routine or procedural knowledge, transfer it cannot account for the tailoring of declarative knowledge observed in adaptive transfer situations. The second mechanism of classic transfer, analogy, operates through three processes: a) identifying an exemplar, b) creating alignment between the exemplar and the current task, and c) drawing inference appropriate for the current task. The third mechanism is knowledge compilation, in which the task perform interprets prior declarative knowledge and forms a set of rules or procedures to accomplish a new task. Knowledge compilation is essentially in scenarios of adaptive transfer. The fourth mechanism is constraint violation, and refers to a three-step process of generating potential solutions to a new problem, evaluating solutions using prior declarative knowledge, and finally revising the solution until a viable solution to the problem is constructed. Each of the four mechanisms described above has been successful in accounting for some, but not all aspects of transfer. Critiques of the classical approach revolve around four main challenges; 1) it provides a limited methodology for assessing transfer which is only focused on direct application, 2) it relies heavily on models of exemplar performance, 3) context for task definition does not consider the students’ purposes and construction of meaning, and 4) it fails to consider knowledge application as a function of activity, social interactions, or culture. Efforts to integrate these mechanisms into a holistic framework have led to a number of alternative approaches to describing the process of transfer. Contemporary Models of Transfer Bransford and Schwartz’s preparation for future learning (PFL) approach focusses on describing how prior knowledge transfers into a new learning situation, thus affecting not only how one learns, but also how this subsequent learning impacts future performance (Bransford & Schwartz, 1999). Lobato’s actor-oriented transfer (AOT), attempts to address the socially Transfer of Learning: Reflections on the foundations of the phenomenon from educational psychology situated nature of transfer, and suggests an interpretative nature to knowing that results in designed objects of knowledge that are prepared for appropriate application by the learner (Lobato, 2012). Lobato focusses on what the learner stands to benefit from transferring their learning, and makes a compelling case for an active learning stance to support subsequent transfer opportunities. Most recently, Nokes-Malach & Mestre’s transfer as sense making approach attempts to integrate the classic mechanisms into cyclical process that the learner follows first in constructing a current representation of context and then in generating a solution (Nokes-Malach & Mestre, 2013). Sense making refers to the act of determining whether the goals of the task have been satisfied based on coordination of prior knowledge with information from the environment. A process model for transfer has also been proposed as a means to describe the movement of knowledge with the business firm (Szulanski, 2002). The four stages and (transitional milestones) of this process model include (formation of the need), initiation (decision to transfer), implementation (first day of use), ramp-up (achievement of satisfactory performance), and integration. The Inquiry of Transfer Studied applications of phenomenon Through the years, studies on the phenomenon of transfer have been conducted across a myriad of different settings. This diversity in field of study includes everything from training undergraduate students using naval radar tracking simulations (Kozlowski et al., 2001), to examining the “Mozart effect” of enhanced spatial-temporal abilities after listening to a Mozart piano sonata in music education (Rausher & Hinton, 2006). Although the scientific exploration of transfer began at the turn of the century by educational psychologists, transfer remains an 6 Transfer of Learning: Reflections on the foundations of the phenomenon from educational psychology 7 undeniably clear foundational goal of instructional design when applied to formal education, informal mentoring, and corporate training. Predictors Based on current evidence, it is generally accepted that behavioral methods of transfer promote near transfer of procedural knowledge; whereas cognitive approaches are more supportive of farther transfer of declarative knowledge. However, there are a number of predictors beyond simply the approach to transfer that influence the success of the learning. In a 2010 meta-analytic review of the literature on transfer (Blume, Ford, Baldwin, & Huang, 2010) the trainee characteristics that appear to have the strongest relationship with transfer include: cognitive (general) ability, conscientiousness, voluntary participation, motivation, and self-efficacy. According to Clark & Voogel (1985), “General ability is the best predictor of transfer under all task conditions (page 120)”. General ability refers to high order cognitive skills such as alertness, selection, connecting, planning, and monitoring. Educational research has commonly found that farther transfer is achieved by students with higher general ability scores. In addition to general ability, transfer also increases when the student is aware of what they know and do not know, and when they possess conditional knowledge of when are why to access certain prior knowledge (Bransford & Schwartz, 1999). Scholars have also found that motivation to learn was positively related to transfer (Colquitt, LePine, and Noe, 2000). Although there is much we still do not know about this complex, bidirectional relationship between motivation and transfer (Goldstone & Day, 2012), Pugh and Bergin (2006) offer three testable hypotheses; 1) motivational factors can influence initial learning in ways that support transfer, 2) motivational factors can influence the initiation of transfer attempts, and 3) motivational factors can influence persistence on transfer tasks. Transfer of Learning: Reflections on the foundations of the phenomenon from educational psychology 8 Additionally, research suggests that self-efficacy also has a positive relation to transfer. Selfefficacy refers to “beliefs in one’s own capabilities to organize and execute the courses of action required to produce given attainments” (Bandura, 1997, page 3). Gist, Stevens, and Bavetta (1991) found that pre-training self-efficacy was significantly related to MBA students’ ability to a transfer task related to salary negotiations. In educational contexts, instructional strategies tend to focus on either mastery or performance goals. Mastery goals refer to an engagement in the task with the purpose of improved competence, whereas, performance goals refer to engagement in the task with the purpose of demonstrating competence in relative terms. Bereby-Meyer & Kaplan (2005) found that learning opportunities that emphasize learning and improvement over social comparisons of competence can enhance the transfer of learning. Further, performance goal orientation may actually interfere with the process of transfer. While social comparisons between students may detract from the ability of learners’ to transfer their knowledge, Engle, Kim, Meyer, and Nix (2012) posit that it is not just the physical aspects of context, but also how social interactions frame learning as particular social realities that matter for transfer. In a tutoring experiment, these authors show how expansive framing, the process of both prompting students to connect the learning environment to the real-world and promote student ownership of learning, promotes transfer. In comparison, bounded framing of the learning, where each learning session is treated as a separate event, tends to discourage transfer activities. Although the nature of the skill to be transferred has not received the same attention in the literature to some of the previously discussed predictors, Blume et al., did find that a general pattern exists in the literature to suggest that the predictors previously discussed tend to have Transfer of Learning: Reflections on the foundations of the phenomenon from educational psychology 9 stronger relationships to transfer with open skills (e.g., leadership) than with closed skills (e.g., financial accounting). Closed skills tend to have more prescribed transfer behaviors, which may explain the diminished impact environmental factors may have relative to transferring open skills. Barriers Many of the same environmental factors that are viewed as predictors of success can alternatively be thought of as potential barriers to the transfer of knowledge. For example, although prior knowledge was discussed earlier as a pre-requisite for cognitive forms of knowledge transfer, Vosniadou (2007) cautions that sometimes prior knowledge can also act as a barrier to transfer. In fact, sometimes school knowledge represents a different explanatory framework from what students have implicitly constructed on their own based on their everyday experiences. In these instances, the considerable effort to re-organization knowledge based on instruction is often sacrificed at the expense of the less challenging rote memorization of superficial facts that are easy forgotten. In Sticky Knowledge, barriers to knowing in the firm, Gabriel Szulanski identified several barriers to best practice transfer, collectively referred to as the “stickiness” of knowledge transfer. In his study, knowledge was transferred within the organization from source (instructor) and recipient (learner). The three most important barriers found in his work include the lack of absorptive capacity of the recipient, causal ambiguity due to a specific piece of idiosyncratic knowledge that is otherwise unknown, and an arduous relationship between the source and the recipient (Szulanski, 2002). Szulanski acknowledges that most contemporary studies of transfer are premised on the observation that knowledge is “something more” than fully codified information. Transfer of Learning: Reflections on the foundations of the phenomenon from educational psychology 10 Reflection Upon this focused review of the literature on the transfer of learning, I am struck by the sheer energy the scholarly community has devoted to studying this phenomenon. From its classical roots in educational psychology, to modern day advances on frameworks and predictors of success, it is clear just how important the practical application of knowledge gained in the classroom is to both instructional designers and researchers. In attempting to reconcile what I have learned through the literature with my own experiences in industry, there are a number of aspects of transfer that both align and diverge with my attempts to reuse firm assets and knowledge. The potential for transfer really starts in the training environment. The literature suggests that active learning and making students aware of transfer opportunities is important to instructional design. I participated in many training courses at Accenture, and I can confirm that in those instances when I was presented with new skills and knowledge in the context of a simulated client engagement made it easier for me to apply those skills once I returned to the workforce. I remember vividly an opportunity I had to practice the selling process with retired Accenture employees in a Senior Manager training course. I remember thinking “wow, this former employee is tough”. Immediately after that training, however, I returned to the client site and was included in new proposal to an existing client. It seemed so easy to take all that I learned in the training course and apply that in the real situation. I can’t imagine how difficult it would have been to work through the negotiation had I not simulated the dialog in the training course I had participated in. The opposite is also true. In the trainings when I was either listening to lecture or working through learning exercises that did not simulate the real-world, I left the training wondering how I would apply what I had just learned. Transfer of Learning: Reflections on the foundations of the phenomenon from educational psychology 11 In addition to the value of active learning, I also agree with the literature on the importance of providing feedback during the learning opportunity. I completed many self-paced training courses and computer-based trainings that did not provide any feedback. In these instances, it was as if I was just wasting time completing an assignment or watching a video. It was always a struggle to think about how what I was learning could be used on the project site. More importantly, I had no idea whether the work that I had completed was appropriate or correct. In one instance, I actually went back to the client site and asked my manager to review the work I had completed in the course. He responded with, “I’m not sure why they asked you to do this, we don’t do it that way in the field.” Conversely, I remember my very first training seminar at Accenture, which was led by two very senior executives. Although I was a bit intimidated, each executive took the time to look over my shoulder, and scored my training output using a predefined rubric. After I had received my assessment, one of the executives met with me and showed me where my work could have been improved. Not only did this motivate me to take the training more seriously, but I realized that if an executive was willing to spend time providing me feedback, it must mean that they were coaching me to the performance they were looking for me to demonstrate when staffed on a project. The one are in the literature that is incongruent with my experience is with respect to the distinction Bereby-Meyer & Kaplan make regarding mastery and performance goals. These authors posit that transfer is made easier when the learner emphasizes mastering the skill over showing competence in performance over peers. While I don’t dispute that learners should not overly obsess on the social comparison, I do believe a little bit of “healthy competition” brings excitement to the learning environment that can serve as a key motivator. For example, we were routinely placed on teams in Accenture training courses, and these teams competed to either Transfer of Learning: Reflections on the foundations of the phenomenon from educational psychology 12 “win the sale” or “deliver the best solution to the client”. So long as the comparison between teams was based on measuring real-world performance examples, I think it is wholly appropriate to compare the learner’s output. In fact, I believe the absence of competition entirely can lead to indifference and participation in the training environment that is void of meaning. Paired with strong feedback, my experience tells me that social comparisons push everyone to stay engaged and focused on the learning opportunity. Conclusion In this whitepaper, I summarized the theoretical foundations of the current literature on the transfer of learning. Beginning with a review of the classical definitions of the process of transfer found in educational psychology, I moved on to discuss more contemporary models that support the appropriation of skills acquired in a training scenario across a wide array of real-world applications. What has emerged is a complex taxonomy to describe transfer, as well as a rich discussion of the both the predictors and barriers to successful transfer. Scholars have studied transfer in a wide array of different settings. Relying on my own experience in a corporate environment, I have found that a many of the findings in these studies, including the need to construct active learning assignments and provide feedback to the learner aligns significantly with my own attempts to transfer. However, I do believe there is merit challenging the assumption that avoiding social comparisons of the learner’s performance enhances their transfer abilities. Transfer of Learning: Reflections on the foundations of the phenomenon from educational psychology 13 References Baldwin, T. T., & Ford, J. K. (1988). Transfer of training: A review and directions for future research. Personnel psychology, 41(1), 63-105. Blume, B. D., Ford, J. K., Baldwin, T. T., & Huang, J. L. (2010). Transfer of training: A metaanalytic review. Journal of Management, 36(4), 1065-1105. Bereby-Meyer, Y., & Kaplan, A. (2005). Motivational influences on transfer of problem-solving strategies. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 30, 1–22. Bransford, J.D., (1979). Human cognition: Learning, understanding and remembering. Belmont, CA:Wadsworth. Chi, M. T., & VanLehn, K. A. (2012). Seeing deep structure from the interactions of surface features. Educational Psychologist, 47(3), 177-188. Clark, R. E., & Voogel, A. (1985). Transfer of training principles for instructional design. ECTJ, 33(2), 113-123. Day, S. B., & Goldstone, R. L. (2012). The import of knowledge export: Connecting findings and theories of transfer of learning. Educational Psychologist, 47(3), 153-176. Engle, R. A., Lam, D. P., Meyer, X. S., & Nix, S. E. (2012). How does expansive framing promote transfer? Several proposed explanations and a research agenda for investigating them. Educational Psychologist, 47(3), 215-231. Goldstone, R. L., & Day, S. B. (2012). Introduction to “new conceptualizations of transfer of learning”. Educational Psychologist, 47(3), 149-152. Lobato, J. (2012). The actor-oriented transfer perspective and its contributions to educational research and practice. Educational Psychologist, 47(3), 232-247. Transfer of Learning: Reflections on the foundations of the phenomenon from educational psychology 14 Mathan, S. A., & Koedinger, K. R. (2005). Fostering the Intelligent Novice: Learning from Errors with Metacognitive Tutoring. Educational Psychologist, 40(4), 257-265. Nitsch, K. E. (1981). Structuring decontextualized forms of knowledge. University Microfilms. Nokes-Malach, T. J., & Mestre, J. P. (2013). Toward a model of transfer as sense-making. Educational Psychologist, 48(3), 184-207. Osgood, C. E. (1949). The similarity paradox in human learning: a resolution. Psychological review, 56(3), 132. Perkins, D. N., & Salomon, G. (2012). Knowledge to go: A motivational and dispositional view of transfer. Educational Psychologist, 47(3), 248-258. Pugh, K. J., & Bergin, D. A. (2006). Motivational Influences on Transfer. Educational Psychologist, 41(3), 147-160. Rauscher, F. H., & Hinton, S. C. (2006). The Mozart Effect: Music Listening Is Not Music Instruction. Educational Psychologist, 41(4), 233-238. Royer, J. M. (1979). Theories of the transfer of learning. Educational Psychologist, 14(1), 53-69. Rumelhart, D.E., & Norman, D.A. (1981). Analogical processes in learning. In J. R. Anderson (Ed.), Cognitive skills and their acquisition. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. Schwartz, D. L., Chase, C. C., & Bransford, J. D. (2012). Resisting overzealous transfer: Coordinating previously successful routines with needs for new learning. Educational Psychologist, 47(3), 204-214. Szulanski, G. (2002). Sticky knowledge: Barriers to knowing in the firm. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Vosniadou, S. (2007). The cognitive-situative divide and the problem of conceptual change. Educational Psychologist, 42(1), 55-66. Transfer of Learning: Reflections on the foundations of the phenomenon from educational psychology 15 Woodworth, R. S., & Thorndike, E. L. (1901). The influence of improvement in one mental function upon the efficiency of other functions. (I). Psychological Review, 8(3), 247-261.