Why CP is Life-saving 2013 (long version) ENG

advertisement

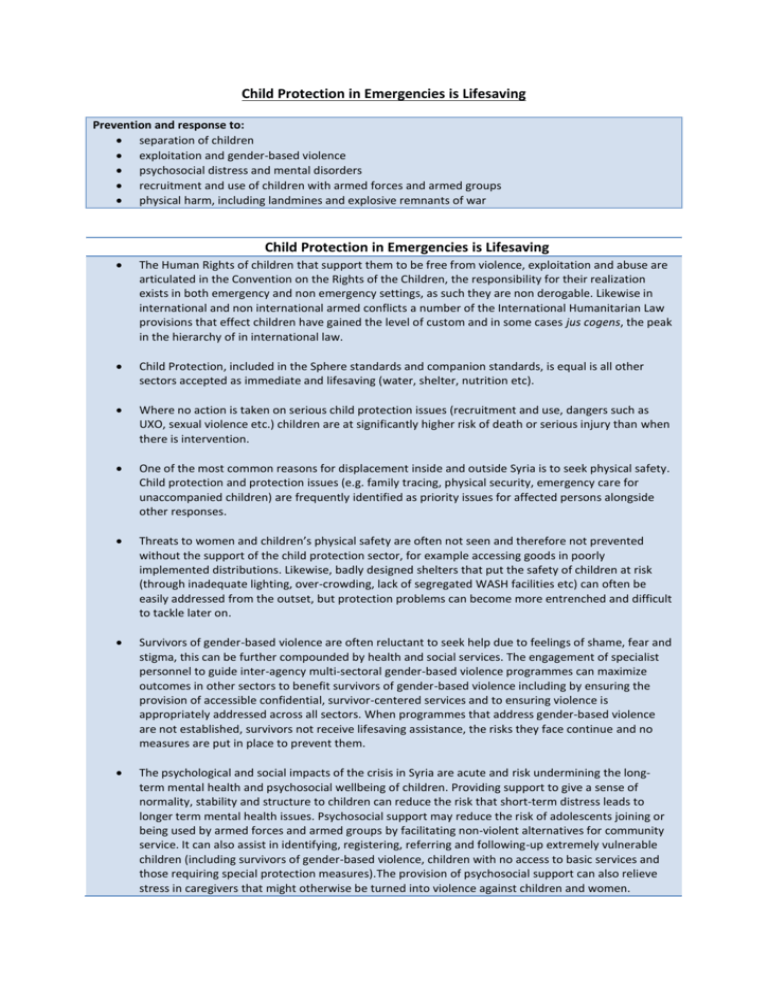

Child Protection in Emergencies is Lifesaving Prevention and response to: separation of children exploitation and gender-based violence psychosocial distress and mental disorders recruitment and use of children with armed forces and armed groups physical harm, including landmines and explosive remnants of war Child Protection in Emergencies is Lifesaving The Human Rights of children that support them to be free from violence, exploitation and abuse are articulated in the Convention on the Rights of the Children, the responsibility for their realization exists in both emergency and non emergency settings, as such they are non derogable. Likewise in international and non international armed conflicts a number of the International Humanitarian Law provisions that effect children have gained the level of custom and in some cases jus cogens, the peak in the hierarchy of in international law. Child Protection, included in the Sphere standards and companion standards, is equal is all other sectors accepted as immediate and lifesaving (water, shelter, nutrition etc). Where no action is taken on serious child protection issues (recruitment and use, dangers such as UXO, sexual violence etc.) children are at significantly higher risk of death or serious injury than when there is intervention. One of the most common reasons for displacement inside and outside Syria is to seek physical safety. Child protection and protection issues (e.g. family tracing, physical security, emergency care for unaccompanied children) are frequently identified as priority issues for affected persons alongside other responses. Threats to women and children’s physical safety are often not seen and therefore not prevented without the support of the child protection sector, for example accessing goods in poorly implemented distributions. Likewise, badly designed shelters that put the safety of children at risk (through inadequate lighting, over-crowding, lack of segregated WASH facilities etc) can often be easily addressed from the outset, but protection problems can become more entrenched and difficult to tackle later on. Survivors of gender-based violence are often reluctant to seek help due to feelings of shame, fear and stigma, this can be further compounded by health and social services. The engagement of specialist personnel to guide inter-agency multi-sectoral gender-based violence programmes can maximize outcomes in other sectors to benefit survivors of gender-based violence including by ensuring the provision of accessible confidential, survivor-centered services and to ensuring violence is appropriately addressed across all sectors. When programmes that address gender-based violence are not established, survivors not receive lifesaving assistance, the risks they face continue and no measures are put in place to prevent them. The psychological and social impacts of the crisis in Syria are acute and risk undermining the longterm mental health and psychosocial wellbeing of children. Providing support to give a sense of normality, stability and structure to children can reduce the risk that short-term distress leads to longer term mental health issues. Psychosocial support may reduce the risk of adolescents joining or being used by armed forces and armed groups by facilitating non-violent alternatives for community service. It can also assist in identifying, registering, referring and following-up extremely vulnerable children (including survivors of gender-based violence, children with no access to basic services and those requiring special protection measures).The provision of psychosocial support can also relieve stress in caregivers that might otherwise be turned into violence against children and women. During emergencies there is an increased risk of violence against children as traditional elements of a protective environment are absent or less effective (such as lack of law and order, disintegration of families and communities, change in some social norms and behavior). This can amplify pre-existing social problems and create new ones, such as gender-based violence and separation of children from their caregivers. Specialized services are needed to connect survivors with assistance, including medical care and counseling. When programmes are not established, not only do survivors not receive lifesaving assistance, the risks they face will continue as no measures will be put in place to prevent them. Financial stress (due to loss of livelihoods, high inflation, depletion of household resources etc) as a result of the crisis places children at higher risk of various forms of exploitation, including worst forms of child labour, child marriage or sexual exploitation. Child protection programmes are needed to strengthen/set-up prevention strategies, as well as to identify, register, refer and follow-up extremely vulnerable children. During population moves and armed conflict, such as shelling and airstrikes, the risk of separation of children from their family members is increased. Child protection programmes are needed to identify, register, and to facilitate family tracing, reunification and emergency care arrangements. When programmes are not established, children are at higher risk of disappearance, exploitation, recruitment and use by armed groups and forces etc. Child protection programmes are needed to provide information on services and support, and to facilitate systematic identification and referral of children in need of assistance (such as healthcare, food, education and shelter). Proliferation of small arms and use of mines, as well as the presence of ERWs and UXO, pose a particular threat to children. The provision of information on physical threats such as avoiding explosive remnants of war can prevent the death and maiming of children. General “Child Protection in Emergencies is Lifesaving” statements: Child Protection, included in the Sphere standards and companion standards, is equal is all other sectors accepted as immediate and lifesaving (water, shelter, nutrition etc). Where no action is taken on serious child protection issues (recruitment and use, dangers such as UXO, sexual violence etc.) children are at significantly higher risk of death or serious injury than when there is intervention. Child protection and protection issues (e.g. family tracing, physical security, emergency care for unaccompanied children) are frequently identified as priority issues for affected persons alongside responses that are already well recognized as immediate and lifesaving. Sub-sector CERF criteria “Child Protection in Emergencies is Lifesaving” Strengthen and/or deploy GBV Survivors of gender-based violence are Gender-based personnel to guide implementation of often reluctant to seek help due to violence an inter-agency multi-sectoral GBV feelings of shame, fear and stigma, this programme response including can be further compounded by health ensuring provision of accessible and social services. The engagement of confidential, survivor-centered services specialist personnel to guide inter-agency to address GBV and to ensuring it is multi-sectoral gender-based violence appropriately addressed across all programmes can maximize outcomes in sectors. other sectors to benefit survivors of gender-based violence including by ensuring the provision of accessible confidential, survivor-centered services Identify high-risk areas and factors driving GBV in the emergency and (working with others) strengthen/set up prevention strategies including safe access to fuel resources (per IASC Task Force SAFE guidelines). Improve access of survivors of gender based violence to secure and appropriate reporting, follow up and protection, including to police (particularly women police) or other security personnel when available. Identification, registration, family tracing and reunification or interim care arrangements for separated children, orphans and children leaving armed groups/forces. Ensure proper referrals to other services such as health, food, education and shelter. Child protection and to ensuring violence is appropriately addressed across all sectors. When programmes that address gender-based violence are not established, survivors not receive lifesaving assistance, the risks they face continue and no measures are put in place to prevent them. Threats to women and children’s physical safety are often not seen and therefore not prevented without the support of the child protection sector, for example accessing goods in poorly implemented distributions. Likewise, badly designed shelters that put the safety of children at risk (through inadequate lighting, overcrowding, lack of segregated WASH facilities etc) can often be easily addressed from the outset, but protection problems can become more entrenched and difficult to tackle later on. During emergencies there is an increased risk of violence against women and children as traditional elements of a protective environment are absent or less effective (such as lack of law and order, disintegration of families and communities, change in some social norms and behavior). This can amplify pre-existing social problems and create new ones, such as gender-based violence and separation of children from their caregivers. Specialized services are needed to connect survivors with assistance, including medical care and counseling. When programmes are not established, not only do survivors not receive lifesaving assistance, the risks they face will continue as no measures will be put in place to prevent them. During population moves and armed conflict, such as shelling and airstrikes, the risk of separation of children from their family members is increased. Child protection programmes are needed to identify, register, and to facilitate family tracing, reunification and emergency care arrangements. When programmes are not established, children are at higher risk of disappearance, exploitation, recruitment and use by armed groups and forces etc. Child protection programmes are needed to provide information on services and support, and to facilitate systematic Identification, registration, referral and follow-up for other extremely vulnerable children, including survivors of GBV and other forms of violence, children with no access to basic service and those requiring special protection measures. Provision of psychosocial support to children affected by the emergency, e.g. through provision of child friendly spaces or other community-based interventions, return to school or emergency education, mental health referrals where expertise exists. identification and referral of children in need of assistance (such as healthcare, food, education and shelter). During emergencies there is an increased risk of violence against women and children as traditional elements of a protective environment are absent or less effective (such as lack of law and order, disintegration of families and communities, change in some social norms and behavior). This can amplify pre-existing social problems and create new ones, such as gender-based violence and separation of children from their caregivers. Specialized services are needed to connect survivors with assistance, including medical care and counseling. When programmes are not established, not only do survivors not receive lifesaving assistance, the risks they face will continue as no measures will be put in place to prevent them. Financial stress (due to loss of livelihoods, high inflation, depletion of household resources etc) as a result of the crisis places children at higher risk of various forms of exploitation, including worst forms of child labour, child marriage or sexual exploitation. Child protection programmes are needed to strengthen/set-up prevention strategies, as well as to identify, register, refer and follow-up extremely vulnerable children. The psychological and social impacts of the crisis in Syria are acute and risk undermining the long-term mental health and psychosocial wellbeing of children. Providing support to give a sense of normality, stability and structure to children can reduce the risk that shortterm distress leads to longer term mental health issues. Psychosocial support may reduce the risk of adolescents joining or being used by armed forces and armed groups by facilitating non-violent alternatives for community service. Psychosocial support programmes can assist in identifying, registering, referring and following-up extremely vulnerable children (including survivors of genderbased violence, children with no access to basic services and those requiring special protection measures). The provision of psychosocial support can relieve stress in caregivers that might otherwise be turned into violence against children and women. Multiple assessments note that the community is the first responder to humanitarian issues, within its collective capacity to cope with resilience. Investment in community mechanisms that support resilience and local response to issues decreases the child protection risks to children and provides an avenue for response Identification and strengthening, or establishment of community-based child protection mechanisms to assess, monitor and address child protection issues. Emergency survey and clearance of temporary resettlement area of displaced population. Emergency Clearance and/or Survey (mines/UXO/cluster bombs) of identified temporary settlement areas or return areas, urban and/or populated areas, access to water, schools etc Mine Risk Education for displaced and/or returning population Mine action Proliferation of small arms and use of mines, as well as the presence of ERWs and UXO, pose a particular threat to children. The provision of information on physical threats such as avoiding explosive remnants of war can prevent the death and maiming of children.