Review of the Standards for the Regulation of Vocational Education

Page i

MOOCs and VET

MOOCs and VET

© 2013 Commonwealth of Australia

With the exception of the NATESE and FLAG Logos, any material protected by a trademark and where otherwise noted, all material presented in this document is provided under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia license: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/

The details of the relevant license conditions are available on the Creative Commons website as is the full legal code for the CC BY 3.0 AU license: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/legalcode

The document must be attributed as: MOOCs and VET: Applying the MOOCs model to vocational education and

training in Australia

Page ii

MOOCs and VET

Table of Contents

Page iii

MOOCs and VET

1.

Introduction, overview and issues

This report has been commissioned by FLAG for submission to the National Senior Officials Committee (NSOC). It seeks to address two key issues:

Is there a case for the application of massive open online courses (MOOCs) to the vocational education and training (VET) sector in Australia?

What is the role for government in MOOCs for VET?

FLAG’s interest in MOOCs springs from its key role as an advisory body on e-learning to NSOC. The MOOCs phenomenon constitutes the most significant development in online education in recent years. Gallagher and Garrett refer to MOOCs in the report ‘Disruptive education: Technology-enabled universities’, as the most significant change to higher education since the development of the printing press, (pp 8-9).

Universities have rapidly moved resources into the production and promotion of MOOCs, commonly citing three major benefits from engagement with the mode:

As a vehicle for the global dissemination of institutional brand

As an identifier of talent

As a means of utilising significant data and analytics to enhance pedagogy and learner outcomes.

The speed with which the sector has moved into the mode indicates the level of risk universities perceive in being left outside the innovation. The extent of this risk was illustrated by the CEO of the UK MOOC platform, Futurelearn,

Simon Nelson, addressing a recent MOOCs conference in Melbourne. Nelson cited the rapid and dramatic falls in revenues for the recorded music industry, the newspaper business and bricks-and-mortar video hire businesses as examples of sectors suffering through a failure to recognise digital technology overtaking their core product, and added to these the question: ‘Isn’t the higher education industry just waiting to be swept away by digital delivery?’

Commenting on the experience of the University of Melbourne, Vice-Chancellor Professor Glyn Davis told the

Australian Financial Review (6 November) that ‘…we took 160 years to build up a student body of 47,000 on our campus and in 10 months we recruited 300,000 people online. That’s the speed of change.’

While a considerable volume of commentary and opinion has been made public on the mode in relation to higher education, little has been produced which links MOOCs to specific opportunities in vocational education and training.

Yet there are significant motivations to consider the application of MOOCs to VET in Australia, including:

The potential to engage learners through low or no-cost, highly effective, targeted e-learning

The ability of the mode to provide high-quality, nationally consistent e-learning materials to large numbers of learners in trade and professional training cohorts

The capacity to engage under-represented groups in society, presenting particular opportunities for digital and language, literacy and numeracy foundation skills

The capacity of the mode to respond with agility to pressing workforce skills-gaps

The capacity for MOOCs to promote Australian VET providers internationally, particularly in the Asia-Pacific region

The capacity of the mode to provide ‘big data’ to achieve efficiencies and make quality improvements in delivery.

Overview

Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) are a relatively new phenomenon to enter the education landscape. The 2013

Austrade report ‘More than MOOCs: Opportunities from disruptive technologies in education’ attributed four key drivers to the ‘likelihood of a major disruption in education systems over the next decade’, being:

(i) A crisis in US higher education characterised by both unsustainably high costs to the consumer, and criticism by employers of the value of the end product

Page 1

MOOCs and VET

(ii) Large volumes of capital being made available from government, philanthropic and business sources to apply new education technology to the crisis set out above

(iii) Unsustainable competition within the US higher education market, with over 5,000 tertiary education providers

(iv) The convergence of technology and consumer demand.

MOOCs were identified early as a ‘disruptive innovation’, defined by Wikipedia as ‘an innovation that helps create a new market and value network and eventually goes on to disrupt an existing market and value network … displacing an earlier technology’.

Clay Shirky describes how MOOCS are disrupting higher education in his article at http://www.shirky.com/weblog/2012/11/napster-udacity-and-the-academy/ .

The first MOOC was delivered in 2008, but the mode experienced rapid uptake in the US in 2011 and 2012. Since then,

MOOCs have been the subject of significant commentary and divergence of opinion in education forums. By mid-

2013, there have been over 5 million MOOC registrations globally (see Appendix). Since their inception, MOOCs quickly demonstrated their ability to attract large numbers of learners, many with limited or no exposure to either online learning or higher education. The gravitas afforded by the involvement of some of the world’s highest ranked universities, including Harvard University, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and Stanford University, has rapidly raised the profile of MOOCs. The New York Times called 2012 ‘The Year of the MOOC’.

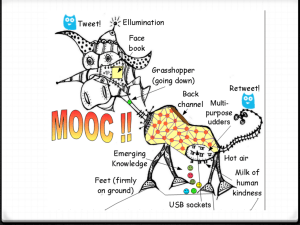

MOOCs provide online learning through structures which build on the connectivity of social media and include: the free video transmission of lectures; provision for learners to participate in online forums or tutorials; a range of assessment tasks including quizzes, essays and interactive peer activities. Course material for MOOCs is provided at no cost, with payment generally made in exchange for assessment and certification of completion.

The use of data and digital analytics in relation to the provision of teaching activities delivered via MOOCs provides real-time insight into the effectiveness of e-learning, accurately mapping learner experience and identifying gaps or stumbling-blocks in the delivery of teaching materials. The use of this data has significant potential to gauge and respond to the experience of the learner, and through this, to raise the quality and effectiveness of e-learning (see

‘Advantages for e-learning pedagogy’ below).

MOOCs function on multiple levels, including as a highly effective marketing channel to demonstrate, in considerable depth, the learning experience, environment and culture of the host institution. The involvement of prestige universities in MOOCs originating in the US has provided unparalleled marketing opportunities for these institutions to engage with a large cohort of learners for whom an experience of these institutions would have been otherwise unattainable. While traditional enrolment at such institutions may remain an aspiration for most, the capacity of

MOOCs to demonstrate the effectiveness and value of online education (or education per se) is a key value in the

MOOCs model.

A range of institutions, including Deakin University and the University of New England (UNE) have developed ways of converting MOOCs undertaken by learners into credits against degree courses. Some US colleges are allowing recognition of prior learning credits for the completion of MOOCs. The US State of California recently confirmed that it would provide academic credit for learners who had undertaken MOOCs in a range of courses in Californian public universities for which oversubscription meant there were no available places.

While the great majority of the activity and accompanying commentary on MOOCs has been focussed on the higher education sector, and specific universities, some MOOC activity within VET has been undertaken both internationally and in Australia. In Australia, local platforms for VET delivery include Open2Study and EduOne (see Appendix).

Internationally, ALISON (Advanced Learning Interactive System Online), an Irish provider of e-learning, has been operating since 2007, and is focussed on the free delivery of online vocational education (see below).

Issues

The flipped classroom

YouTube video: ‘How the flipped classroom works’, Mediacore, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iQWvc6qhTds

While the emphasis in MOOCs to date has been on theoretical subjects, it is relevant to note that MOOC practice has seen the traditional paradigm of classroom and individual learning ‘flip’. Traditionally, learners were asked to come to

Page 2

MOOCs and VET lectures having read a text prior to attending a lecture to facilitate understanding of the information being conveyed,

(mainly one-way), to them by the lecturer. In the ‘flipped’ classroom, students undertake the preparatory learning online, freeing up class time for more valuable, interactive teaching and learning activities.

In the ‘flipped’ MOOC model, video lectures are watched at learners’ own pace prior to the group convening in ‘virtual classrooms’ to interact with both the teacher and other learners on practical exercises, lab-work and assessment tasks, many of which would align with the competency-based tenets of VET learning. Research is indicating that courses that move to the ‘flipped’ model achieve much higher rates of retention and completion.

Industrial relations

The advent of MOOCs raises a number of complex issues including fundamental questions about the role of the teacher and the nature of teaching. The University of Western Australia announced in June 2013 that it would use a

Stanford MOOC to replace lectures for its second-year course, ‘Introduction to databases’.

Some higher education professionals have expressed doubt about the capacities of the MOOC model to deliver quality teaching, and have voiced concerns that institution management may seek to make savings through the removal of teaching staff and replacement with online alternatives.

The National Tertiary Education Union (NTEU) has expressed its concerns about the adoption of MOOCs and what this might mean for members.

Some questions around these issues might be:

Will the MOOCs model displace the requirement for teachers as we know them?

Will current teaching jobs be downgraded to classroom assistant status or similar?

Are online teaching materials the new currency for teachers? Will teachers be remunerated as IP producers, paid for the delivery of key course materials and perhaps, on a royalties or ‘per view’ basis?

Can institutions reliably provide high-quality teaching and learning outcomes from MOOCs?

Could VET’s engagement with MOOCs prompt calls for the possible decommissioning of extant VET infrastructure?

MOOCs and completions

While enrolment data for MOOCs has included some very large numbers of learners, completion rates recorded for

MOOCs have been low – an average completion figure of 7% is often cited.

It should be noted that analytics demonstrate that by far the greatest number of learners leave courses before undertaking the first learning exercise (quiz, assessment or interactive peer activity). This demonstrates that there are a variety of motivations for enrolment within a MOOC, and illustrates the difficulty in comparing open online enrolment to the far more regulated, ‘bricks-and-mortar’ institutional enrolment.

The founders of US MOOCs platform Coursera (see below) recently addressed this issue a recent article, ‘Retention and intention in massive open online courses: In depth’ which details the experience of Coursera’s significantly raised completions under the ‘Signature Track’ system.

‘An even more compelling indicator of intent can be found in Coursera's recently announced

Signature Track. This recently developed optional program, available in selected MOOCs, provides students with a way to earn a more official credential for their accomplishments by participating in keystroke biometric and photo-based identity verification. Students enroll in

Signature Track early in the course (week 2 or 3), pay a fee ($30–$100) for the identityverification services, and earn an identity-verified, university-branded credential if they pass the course.

Signing up for Signature Track is a clear statement by students that they intend to complete the course and earn a credential. In the first Signature Track class, ‘Nutrition for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention’ taught by Professor Katie Ferraro from the University of California, San

Francisco, the completion rate among paying Signature Track students was 74 percent

Page 3

MOOCs and VET compared to 9 percent in the non-Signature Track population (figure 4). Moreover, among students who indicated a strong intent to finish in a survey administered one month into the course, after the Signature Track signup deadline, completion rates were higher in the paying group (96 percent vs. 84 percent, p = 0.0009), suggesting that having a financial stake may provide an additional incentive to finish.’

Under the ‘Signature Track’ arrangements completions were raised to over 70%. A detailed analysis of relevant retention data is provided at http://www.educause.edu/ero/article/retention-and-intention-massive-open-onlinecourses-depth-0

A recent development of longstanding e-learning and distance-learning practice

MOOCs draw on elements of distance and online learning that have been practiced for many years. These include the use of video lectures, interactive tutorials facilitated online, real-time peer interaction, interactive peer assessment and 24/7 access to training materials. The MOOC model adds two further, new dimensions:

(i) the scale of the MOOC learning environment, which may number in the thousands or tens of thousands

(ii) the global reach of the virtual MOOC classroom.

Page 4

MOOCs and VET

2.

The extent of institutional engagement with MOOCs in Australia

Australian VET sector engagement with MOOCs has been limited. Two key examples are:

EduOne - http://www.eduone.net.au/

A collaboration between the University of New England (UNE) and TAFE NSW-New England, Institute EduOne provides higher education and VET pathways into further study at UNE and TAFE New England, and offers open educational resources in a limited range of topics and the capacity for recognition of prior learning credits toward TAFE qualifications at TAFE NSW New England Institute. These appear to be appropriately described as open education resources rather than MOOCs; they do not provide for the facilitated, social media-type connection of students.

Open2Study - https://www.open2study.com/

Open2Study was initiated by Open Universities Australia in partnership with its 20 higher education and VET sector members. It currently offers 27 free online courses including: ‘Astronomy: Discovering the Universe’; ‘Basic Physics’,

Diagnosing the Financial Health of a Business’, ‘Principles of Project Management’; ‘Online Advertising’, and

‘Understanding the Origins of Crime’. These open educational resources provide pathways to higher education and

VET qualifications on offer through Open University institutions.

Engagement with higher education is more extensive. Some key examples are:

Australian National University (ANU) - In partnership with EdX, ANU is offering ‘Astrophysics’ and ‘Engaging India’

– both will go online in 2014

Deakin University - Through its own platform, DeakinConnect, Deakin is currently offering ‘Humanitarian

Responses to 21 st Century Disasters’

Swinburne University of Technology - Through Open2Study, Swinburne is currently offering ‘Concepts in Game

Development’, ‘Basic Physics’, ‘Innovation for Powerful Outcomes’; from later in 2013, Swinburne will be offering

‘Basic Chemistry’ and ‘Robotics’

University of Melbourne - In partnership with Coursera, the University of Melbourne is offering seven current

MOOCs, and is currently the 20 th largest provider of MOOCs worldwide, with 300,000+ enrolments

Through 2013, the University has offered: ‘Animal Behaviour’, ‘Principles of Macroeconomics’; ‘Generating the

Wealth of Nations’; ‘Discrete Optimization’; ‘Epigenetic Control of Gene Expression’; ‘Exercise Physiology -

Understanding the Athlete Within’; and ‘Climate Change’. A further three courses are scheduled to be offered in

2014: ‘Sexing the Canvas’, ‘Online Logic’, and ‘Global Adolescent Health’

University of New South Wales - UNSW signed with Coursera in July 2013. Offerings in science and engineering will be available from 2014.

Page 5

MOOCs and VET

3.

Drivers for VET

Drivers for application of the MOOC model to deliver high-quality outcomes for the Australian VET sector have been identified in a number of areas, including improved quality in VET delivery; for enhancements to learner access and equity within the national training system, and to exploit the capacities of the national broadband network in both the delivery of learning materials and interactions within the ‘virtual classroom’.

There are also potential opportunities for VET in the global promotion of the Australian VET sector, and the provision of tailored and responsive professional development material.

As part of the broader VET quality agenda

MOOCs provide an opportunity to improve outcomes, completions and quality by use of the ‘flipped classroom’ model to provide high quality, nationally consistent off-the-job e-learning for vocational learners.

High quality materials could be produced by an individual RTO or consortia, and the e-learning activities could be supported by hands-on, practical labs and tutorials undertaken by VET providers locally.

Apprentices could undertake required off-the-job training via MOOC – this would enable apprentices to undertake required training at a time to suit them and their employer.

It could provide major opportunities for peer-to-peer and other collaborative learning, and provide a mechanism for the early completion of apprenticeships.

The ‘big data’ provided through MOOCs can provide insights into the achievement of efficiencies within the system, and point to areas for quality improvements in delivery

The MOOC model provides the opportunity to curate a huge amount of e-learning on the internet to pinpoint specific training and skills needs, and to ensure that material is current and of high quality.

We have previously made considerable investments in online content (toolboxes). This was created as high quality material, but tended to date quickly. MOOCs provide an opportunity to re-examine the model and work out new and better ways to create high quality content, eg providers could collaborate to produce a high quality

MOOC on specific themes, reducing costs and raising quality

MOOCs may also provide a solution to address particular challenges around ‘thin markets’ in VET sector delivery

In relation to access and equity

MOOCs could be a useful platform for delivery of foundation skills, including digital literacy, language, literacy and numeracy, and information age employability skills, with potential to enhance access and equity initiatives in line with NSOC objectives.

The mode has the capacity to reach NEET (not engaged in education or training) cohorts including a youth sector with very high rates of digital literacy and engagement.

Provides opportunity for potential learners to ‘try before they buy’ – this has specific resonance for new learners and is of particular value in connection to Certificate I and Certificate II offerings.

To utilise the capacity of the National Broadband Network

MOOCs would utilise the capacity of the National Broadband Network to deliver high-resolution real-time video for both the delivery of learning materials and for the purposes of teacher – learner and learner - learner interactions online.

To broaden the potential e-learning client base, and promote Australian VET internationally

Provides opportunity for e-learning to go beyond the requirements of industry, into the life-long learning space.

Offers opportunity to effectively brand Australia’s high quality VET internationally.

The Commonwealth has identified, through discussions with UNESCO, the potential for the Australian VET sector

Page 6

MOOCs and VET to leverage its high standing in the Asia-Pacific region by introducing specific providers and courses to the Asian market through MOOCs.

The Indian market would appear to offer particular opportunities for Australian VET providers. ACPET reported following its India Forum in June 2013 the expectation that within the next 5 years, over 75 million young people are expected to join the Indian workforce, representing very major opportunities within the rapidly expanding

Indian VET market, and that the Indian government is seeking the support of international VET providers to assist in the delivery of the education and training of some 500,000 citizens by 2020.

To provide professional development

MOOCs provide an excellent platform for professional development.

Approaches to PD are changing - people are now curating PD to suit themselves and their career aspirations.

Employer requirements for ‘soft’ skills, (such as team skills, strategy, agility, technical competence, global focus), do not necessarily fit with structured PD products or courses – employers are more likely to find these in smaller learning ‘chunks’.

The Mozilla Open Badges system is being used by job-seekers and others to demonstrate skills to potential employers and peers. The Open Badge Infrastructure (OBI) provides recognition for skills developed both in traditional learning environments and externally. More information is available at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mozilla_Open_Badges

Efficiencies to emerge from the MOOCs model could include fewer providers and more consistent, higher quality; larger enrolments in individual courses could mean more and better ideas, and through these, increased innovation.

The mode may also have specific value in workforce development applications, eg rapid, national approaches to skills shortages in key sectors.

Page 7

MOOCs and VET

4.

What is the role for government, if any, in engagement of the VET sector with MOOCs?

There is no regulatory or legislative reason that publicly funded VET providers may not engage learners with MOOCs.

In its current review of the Standards for VET, the NSSC has indicated explicitly that it wishes to keep the standards mode-neutral, i.e., that there should be no specific delivery standard for e-learning or MOOCs.

Any MOOCs providing credit toward AQF qualifications would need to operate within the requirements of the AQTF and NVR standards.

Outside of the regulation of provider quality, possible government responses on the engagement of VET with MOOCs could take a number of forms.

Level 1: No role for government, watching brief to be maintained on MOOCs

In the words of Gallagher and Garrett, ‘We believe that when it comes to the challenges and opportunities of technology-enabled education, the most important way governments can help public universities is not to give them more money but to get out of the way so they can innovate’ (p 13).

This could be applied to publicly funded VET as well. FLAG could be tasked to maintain a watching brief and report as required to NSOC on further relevant developments.

Level 2: Government promotes, encourages and funds MOOCs for VET for specific purposes, e.g. workforce development, vocational guidance, etc.

Government could promote or encourage the utilisation of the MOOC model through:

Identification of potential opportunities for VET engagement

Dissemination of relevant data to the VET sector

Inclusion of the subject of MOOCs on relevant agendas of relevant forums

Through provision of funds and other support, government could encourage VET providers to respond to national workforce development issues

To deliver high-quality vocational guidance materials, particularly in response to identified skills shortages, such as:

Open2Study’s Introduction to Nursing in Healthcare – providing an introduction to nursing and what a career nursing in healthcare might involve: https://www.open2study.com/subjects/introduction-to-nursing-inhealthcare

University of Tasmania’s current ‘Understanding dementia’ MOOC, which responds to a 2011 Productivity

Commission report into aged care which predicted that Australia would need to quadruple numbers in the sector by 2050 to cope with the ageing population and increasing numbers of dementia sufferers: http://www.utas.edu.au/wicking/wca/mooc

EduOne’s Introduction to Construction – provides a ‘ten hour taster resource exploring the world of construction’, intended to provide vocational guidance to anyone considering a career in a range of construction trades: http://www.eduone.net.au/module/building-a-life-dream

Level 3: Government to encourage and fund significant demonstration projects; possible public/private partnerships; seed funding for specific MOOC projects to respond to identified needs

Projects could be developed to demonstrate the utility of the MOOC model to VET through FLAG policy research funds

Proposals could address significant issues - eg in response to Australian Workforce and Productivity Agency

Page 8

MOOCs and VET

(AWPA) reports, such as recent AWPA publications on workforce issues for the retail sector and the ICT sector

These could be developed by single RTOs or consortia

ISCs could be involved in identification of most pressing needs, and partner in project development

Peak bodies could consult as appropriate.

Level 4: Government to exercise a regulatory role

This could be either through regulatory standards around delivery, where MOOCs lead to the award of an AQF qualification, or through contractual standards, e.g. determining the suitability of MOOCs for particular programs, e.g. apprenticeships.

Page 9

MOOCs and VET

5.

Risks

One of the most common questions asked about MOOCs is how they can be sustainable – what is the business model?

Where is this technology going and how can it be sustainably funded?

The most obvious risk for providers is that MOOCs rely upon the free distribution of their intellectual property, ie the courseware, but there is as yet no identified business model for the generation of income or the amortisation of costs involved in the production of this material.

The links below provide some indications of how the mode might be funded into the future.

MOOCs: An innovation looking for a business model

The links below examine approaches to possible business models for MOOCs.

First, David Glance, Director, Centre for Software Practice at the University of Western Australia speculates on generating profit by giving something away for free: http://theconversation.com/the-business-of-moocs-how-to-profit-from-giving-away-something-for-nothing-12141

Donald Clark suggests 20 possible methods of monetising MOOCs, including investment, advertising and a recruitment referral service for alumni: http://donaldclarkplanb.blogspot.co.uk/2013/06/20-ways-to-monetise-moocss.htm

In the context of VET and the national training system, the discrete value proposition for stand-alone activities such as those provided through MOOCs (as opposed to accredited courses/ units/ skill sets, etc), needs to be identified.

Where are the greatest opportunities to apply this model? How might it fit into the greater scheme of VET? These questions could be catalysts for further research by FLAG.

MOOCs raise significant implications for Australian education and training models, in areas including staffing numbers, roles for teaching staff, the nature of institutional infrastructure, etc.

Significant copyright and IP issues have also been raised by MOOC delivery within the higher education sector.

Whereas an institution’s open distribution of its own intellectual property is not an issue, the situation becomes problematic when others’ IP is used as part of an Australian MOOC. In this, the Australian context differs markedly from the US, where copyright law is considerably less stringent and prescriptive. These issues are the subject of ongoing and complex examination by the Australian Law Reform Commission, through its current enquiry into

‘Copyright and the Digital Economy’.

Page 10

MOOCs and VET

6.

Advantages for e-learning pedagogy

Using MOOC Data and Analytics: How real-time analysis of learners can improve outcomes

The scale of MOOCs, with enrolments in individual courses of thousands, and sometimes tens of thousands of learners, provides new and compelling opportunities in the development and refinement of online learning pedagogy.

In her video presentation (see video link at section 7), Professor Daphne Koller explains the benefits for teachers of being able to observe and respond to the learning behaviours of large numbers of students simultaneously.

When common errors are identified, materials can be adjusted to ensure that clearer linkages in the flow of learning are made, with a resulting increase in successful completions. This capacity to effectively improve learner outcomes is a key innovation of the MOOC model.

In the VET context, the ability to intervene to improve approaches to e-learning may be of particular benefit in light of the capacity to improve marks and raise completions.

There have been no specific pedagogical barriers identified in applying the MOOC model to vocational education and training, but it may be more readily adapted to theoretical aspects of training, typically delivered ‘off the job’.

The capacity for highly complex manual and technical tasks to be taught effectively utilising online technologies has been demonstrated – see Norton’s example of aural surgery taught through a surgery simulator developed collaboratively by the CSIRO and the University of Melbourne (Norton, p27). The capacity of the NBN to allow realtime high-definition videoconferencing may also contribute to the capacity for further innovation in this regard.

Page 11

MOOCs and VET

7.

Can MOOCs facilitate beneficial access and equity outcomes?

The MOOC model has demonstrated its worth in the capacity to engage learners otherwise excluded from education, including on a global scale (see Koller, below). In this, there are perceptible resonances with the participation and access objectives articulated through NSOC’s priorities.

The model has the potential to engage under-represented demographics, as it is low or no-cost, and depends only upon internet connectivity for access.

MOOCs also reverse the current paradigm whereby learners enrol, pay for their courses, and then undertake learning, including relevant assessment, to obtain qualifications. Learners have paid for their course whether it is completed successfully or not. Under the MOOC model, enrolment and learning happen first, and payment is made in exchange for assessment and final certification of completion. Alternatively, learners may choose not to undertake assessment, thus incurring no charge. Elements of this model are of potential interest to the VET sector from an access and equity perspective.

MOOCs could be especially useful for foundation skills, including digital foundation skills, for foundation skills in language, literacy and numeracy, and the development of skills for employability in the information age.

The capacity for learners to utilise freely available courseware offered through MOOCs is a further area of possible benefit in the context of VET.

These issues raise important questions about societal access to ICT: universal access to education through the use of the internet cannot be assumed. While the spread of internet connectivity and the take-up of broadband have been rapid and far-reaching, there are still issues of engagement, borne out in current figures from the Australian Bureau of

Statistics which show that while 73% Australian of households have broadband access, 20% of people state that they

‘do not use the internet’.

Page 12

MOOCs and VET

References

Australian Trade Commission, More than MOOCs: Opportunities arising from disruptive technologies in education,

2013

Barber, M., Donnelly, K., Rivzi, S., An avalanche is coming: Higher education and the revolution ahead, Institute for

Public Policy research, UK, 2013

Clark, D., http://donaldclarkplanb.blogspot.co.uk/2013/06/20-ways-to-monetise-moocss.html

The Conversation, http://theconversation.com/the-business-of-moocs-how-to-profit-from-giving-away-somethingfor-nothing-12141

Educause review online, http://www.educause.edu/ero/article/retention-and-intention-massive-open-online-coursesdepth-0

Gallagher, S., Garrett, G., Disruptive education: Technology-enabled universities, United States Studies Centre/NSW

Trade and Investment, 2013

Koller, D., What we’re learning from online education, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U6FvJ6jMGHU

Mediacore, How the flipped classroom works, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iQWvc6qhTds

Norton, A., The online evolution: When technology meets tradition in higher education, Grattan Institute, 2013

Shirky, C., http://www.shirky.com/weblog/2012/11/napster-udacity-and-the-academy/

Yuan, L., Powell, S., MOOCs and open education: Implications for higher education white paper, CETIS, UK, 2013

Page 13

MOOCs and VET

Appendix 1. A brief history of MOOCs

YouTube videos

‘What is a MOOC?’

Dave Cormier, Canadian educator and academic, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eW3gMGqcZQc

Following the path of the Open Education movement and the concept of Open Education Resources (OERs), the term

Massive Open Online Course (MOOC) was initially coined in 2008 by Canadian educator and academic

Dave Cormier to describe the ‘Connectivism and Connective Knowledge’ course developed by Canadian education academics Stephen Downes and George Siemens. The course began as a closed learning community of 25 enrolled and fee-paying members, but when membership was widened through open internet access to accept all learners, the course recorded over 2,300 participants.

‘Welcome to the Brave New World of MOOCs’

New York Times, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KqQNvmQH_YM

MOOCs gained greater attention after Sebastian Thrun, a professor of computer science and robotics, ran an open

‘Artificial Intelligence’ course through Stanford University in 2011, attracting over 160,000 learners.

Andrew Ng, one of the founders of Coursera, also from Stanford, was famously quoted in the New York Times on 15

May 2012 on the scale of teaching afforded by MOOCS: ‘‘I normally teach 400 students,’ Ng explained, but last semester he taught 100,000 in an online course on machine learning. ‘To reach that many students before,’ he said, ‘I would have had to teach my normal Stanford class for 250 years’.’

Major MOOC platforms

‘What is a MOOC Platform?’ http://www.thegoodmooc.com/2013/05/what-is-mooc-platform.html

MOOCs are operated through hosting platforms which provide computing and communications services to enable online teaching materials to be delivered. Platforms have assumed a variety of organisational models. Companies that provide the platforms access content through a variety of licensing and support arrangements.

EdX is a non-profit organisation co-founded by Harvard University and MIT. It currently has 28 partner institutions globally, including the Australian National University (ANU) and the University of Queensland, and approximately one million students. EdX President and MIT Electrical Engineering Professor Anant Agarwal has recently stated that EdX aims to provide free online education to one billion people by 2020. https://www.edx.org/

Coursera was founded by Stanford academics Daphne Koller and Andrew Ng, and was initiated with four partner universities, which included Stanford and Princeton. At mid-2013, it has approximately 80 partner universities, including the University of Melbourne and the University of New South Wales. Enrolments exceeded 4 million in

June 2013. https://www.coursera.org/

Sebastian Thrun left Stanford in 2012 to start Udacity, one of the major initial platforms for the delivery of

MOOCs. Udacity is established as a for-profit company, with courses provided from a range of US universities.

With enrolments numbering over 200,000, Thrun has recently stated his hope for half a million enrolments through Udacity. https://www.udacity.com/courses

The UK firm Futurelearn, which involves a consortium of 23 institutions, including Monash University, expects to roll out the UK national platform in September 2013. http://futurelearn.com/

Australian platforms include:

Page 14

MOOCs and VET

Open2Study, initiated by Open Universities. https://www.open2study.com/

EduOne, initiated in collaboration between the University of New England and TAFE New England. http://www.eduone.net.au/

Deakin University’s stand-alone platform, DeakinConnect. http://www.deakinconnect.com

Other organisations of interest

Alison (Ireland) – 250k + graduates - http://alison.com/

ALISON has an emphasis on vocational education. It is funded through site advertising.

‘ALISON (Advance Learning Interactive Systems Online) is an e-learning provider founded in Galway, Ireland in 2007 by social entrepreneur, Mike Feerick. ALISON is cited in industry literature as the first MOOC, pioneering the systematic aggregation of online interactive learning resources made available worldwide with a freemium model. Its stated objective is to enable people to gain basic education and workplace skills. Contrary to other MOOC providers with close links to American third level institutions such as MIT and Stanford University, the majority of ALISON's learners come from outside the extant University system with a focus on the provision of high quality vocational courses. Most of ALISON's users are located in the USA and UK with additional uptake notable in the developing world. India has featured as their fastest growing marked since 2012. ALISON has delivered 60 million lessons and records 1.2 million unique visitors per month; there are 250,000 graduates of its 500+ courses as of January 2013.’

(Source: Wikipedia).

Khan Academy (USA) – 10m+ enrolments - http://www.khanacademy.org/

Khan Academy is supported by a philanthropic funding from corporate and private organisations including Google and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

‘The Khan Academy is a non-profit educational website created in 2006 by educator Salman Khan, a graduate of MIT and Harvard Business School. The stated mission is to provide ‘a free world-class education for anyone anywhere’.

The website supplies a free online collection of more than 4,500 micro lectures via video tutorials stored on YouTube teaching mathematics, history, healthcare, medicine, finance, physics, chemistry, biology, astronomy, economics, cosmology, organic chemistry, American civics, art history, macroeconomics, microeconomics, and computer science.

Khan Academy has delivered over 260 million lessons.’ (Source: Wikipedia).

The crisis in US higher education that gave rise to MOOCs

MOOCs evolved primarily in the US in response to multiple negative factors prompting a critical examination of the US higher education system.

By 2010-11, the cost of higher education in the US had risen to the point that parents, students and employers were simultaneously questioning the value of college education.

At the same time, the advent and popularity of high-quality open education resources, supported by advancing internet technology and the low-cost ubiquity of broadband, enabled access to online learning to very large cohorts.

The will of key university providers (including MIT, Harvard, Stanford, etc) and their takeup of MOOCs to advance their objectives in marketing, branding and positioning, provided significant further impetus.

Page 15

Page 16

MOOCs and VET