N O T E

IFAD-IFPRI Partnership Program - Climate Mitigation Activity

FEBRUARY 2012

2033 K Street, NW, Washington, DC 20006-1002 USA • T: +1-202-862-5600 • F: +1-202-467-4439 • www.ifpri.org

National-level Crop Mitigation Potential for key Food Crops in

Vietnam

William Salas, Changcheng Li, Pete Ingraham, Mai Van Trinh, Dao The Anh, Nguyen Ngoc Mai and Claudia Ringler

Vietnam remains a country heavily grounded in agriculture. In 2010,

approximately 63% of the working population was active in

agriculture. By 2020, the share is expected to still be 59%. The rural

areas also harbor the majority of Vietnam’s poor people. At the

same time, Vietnam has enjoyed very rapid growth across all major

sectors, with overall GDP growth of 6-8% over the last decade. As a

result, greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions per capita have increased

exponentially. While Vietnam is responsible for a very small share of

global greenhouse gas emissions, the country accounts for a

significant share of GHG mitigation potential through improved

agricultural practices as well as improvements in other sectors.

Emissions reductions in agriculture could be a source of millions of

dollars a year of income for farmers in the country, which could be

used by farmers to adapt to the adverse consequences of climate

change.

The importance of agricultural mitigation has recently been

affirmed by the Government of Vietnam through Decision 3119

/QD-BNN-KHCN of Dec 16, 2011, which suggests to reduce, by 2020,

by 20% total GHG emissions in the agriculture and rural

development sector (~19 million tons of CO 2 equivalent), while

reducing poverty and continue agricultural and economic growth

and effectively respond to climate change. While this is a tall order,

the country is well equipped to make significant advances in this

regard.

This brief is based on a study to assess emissions from the

production of key food crops in Vietnam and to assess the potential

of alternative mitigation options in agriculture.

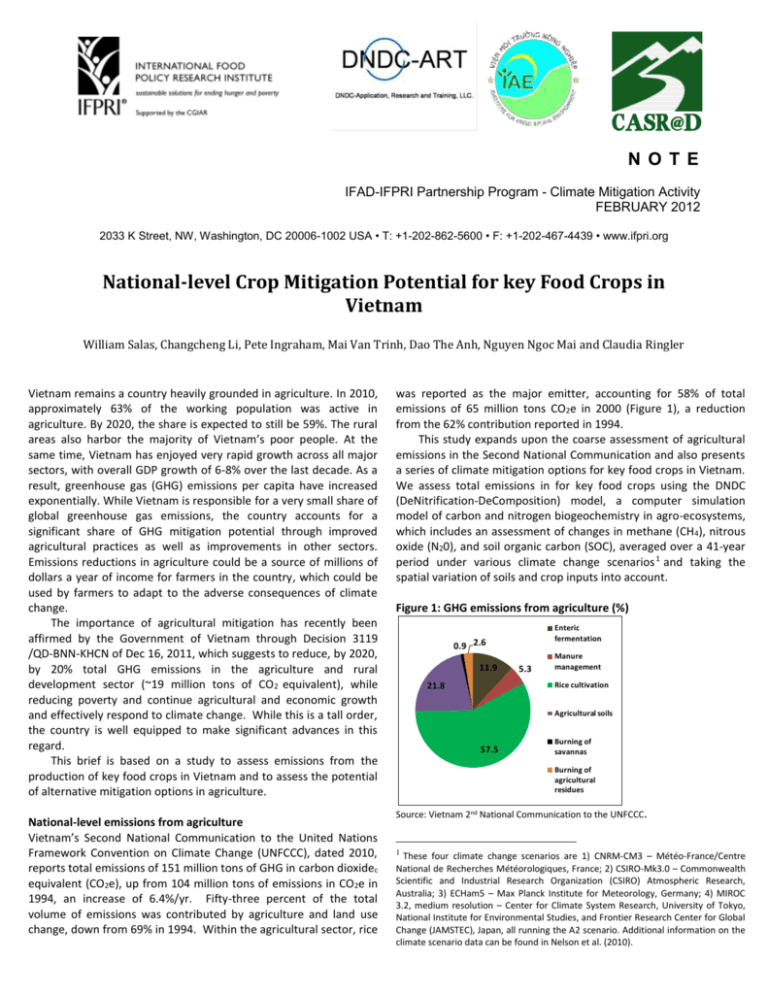

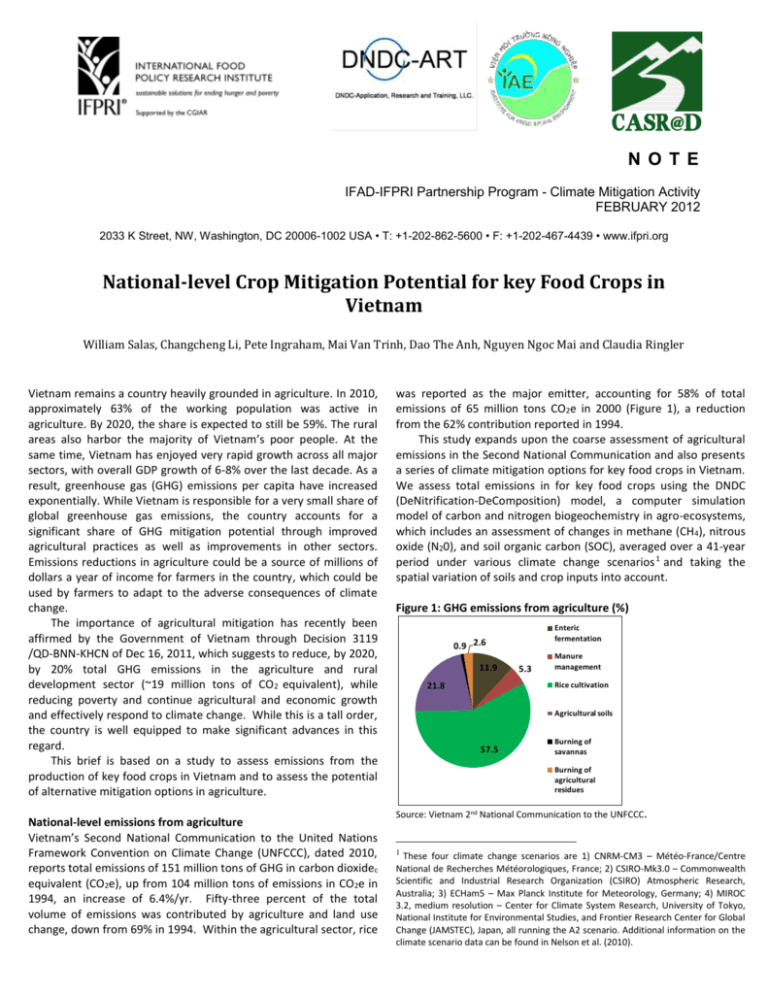

National-level emissions from agriculture

Vietnam’s Second National Communication to the United Nations

Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), dated 2010,

reports total emissions of 151 million tons of GHG in carbon dioxidec

equivalent (CO2e), up from 104 million tons of emissions in CO2e in

1994, an increase of 6.4%/yr. Fifty-three percent of the total

volume of emissions was contributed by agriculture and land use

change, down from 69% in 1994. Within the agricultural sector, rice

was reported as the major emitter, accounting for 58% of total

emissions of 65 million tons CO2e in 2000 (Figure 1), a reduction

from the 62% contribution reported in 1994.

This study expands upon the coarse assessment of agricultural

emissions in the Second National Communication and also presents

a series of climate mitigation options for key food crops in Vietnam.

We assess total emissions in for key food crops using the DNDC

(DeNitrification-DeComposition) model, a computer simulation

model of carbon and nitrogen biogeochemistry in agro-ecosystems,

which includes an assessment of changes in methane (CH 4), nitrous

oxide (N20), and soil organic carbon (SOC), averaged over a 41-year

period under various climate change scenarios 1 and taking the

spatial variation of soils and crop inputs into account.

Figure 1: GHG emissions from agriculture (%)

Enteric

fermentation

0.9 2.6

11.9

5.3

Manure

management

Rice cultivation

21.8

Agricultural soils

57.5

Burning of

savannas

Burning of

agricultural

residues

Source: Vietnam 2nd National Communication to the UNFCCC.

1

These four climate change scenarios are 1) CNRM-CM3 – Météo-France/Centre

National de Recherches Météorologiques, France; 2) CSIRO-Mk3.0 – Commonwealth

Scientific and Industrial Research Organization (CSIRO) Atmospheric Research,

Australia; 3) ECHam5 – Max Planck Institute for Meteorology, Germany; 4) MIROC

3.2, medium resolution – Center for Climate System Research, University of Tokyo,

National Institute for Environmental Studies, and Frontier Research Center for Global

Change (JAMSTEC), Japan, all running the A2 scenario. Additional information on the

climate scenario data can be found in Nelson et al. (2010).

Results for Crop-level Emissions

Across the four scenarios, total food crop emissions vary from 95 to

98 million tons of CO2e. Results for the CNRM Global Circulation

Model fall in the middle of that range. Under this scenario,

emissions from food crops add to 97 million tons of CO2e, 2.6 times

the level reported in the Second National Communication for 2000.

As expected emissions were largest for rice (77 million tons of

CO2e), followed by sugarcane (9 million tons of CO2e) (Table 1).

Emissions per ha are highest for sugarcane, followed by rice.

For all mitigation scenarios we assume a 100% adoption across the

crop area and report 41-year average results under the CNRM A2

climate change scenario. Figures 2 and 3 present changes in GHG

emissions and rice yields, and changes in emissions for upland

crops, respectively. For rice, dry seeding and AWD provide the

largest emission reduction benefits but yields also slightly decline.

Yields increase under ASF, NUE and straw manure. For upland

crops, NUE is beneficial for most crops and yields changes (not

shown) are always positive. Here, ASF increases emissions

considerably, and biochar leads to small emission increases.

Table 1: Emissions per ha and total emissions, CO2e, food crops,

Vietnam

Figure 2: Changes in GHG emissions and yields, rice, alternative

mitigation strategies, compared to baseline (CNRM scenario) (%)

Ton CO2e/ha

million tons of CO2e

yield change (line)

emissions change (column)

Rice

20

77.32

4

40

Sugarcane

28

8.68

2

20

7

3.36

Cassava

12

2.96

0

0

Peanut

10

2.39

-2

-20

Soybean

17

2.17

-4

-40

Source: Authors.

-6

-60

The main GHG sources and sinks include change in SOC, CH4and N20.

According to our results, SOC is a net sink for all key food crops.

Methane is only a major source for rice. Nitrous oxide emissions

(converted into ton/kg CO2e) is a major emissions source for

sugarcane, followed by soybean and cassava and a minor source for

rice.

-8

-80

-10

-100

Maize

Total

96.88

Alternative Mitigation Options

For rice, we assessed the following alternative agricultural

mitigation options: 1) Ammonium sulfate fertilizers (ASF), 2)

Alternate wet and dry irrigation (AWD), 3) Biochar, 4) Compost

manure, 5) Dry seeding, 6) Improved Nutrient Use Efficiency (NUE)

and 7) Straw Manure. Table 2 presents an overview on the

implementation of these alternative management practices with

DNDC.

Source: Authors.

Figure 3: Changes in GHG emissions for upland crops, alternative

mitigation strategies, compared to baseline (CNRM scenario) (%)

30

25

20

15

10

5

0

-5

Table 2: Alternative Agricultural Mitigation Options

Intervention

Ammonium Sulfate

Fertilizer (ASF)

Alternate Wetting &

Drying (AWD)

Biochar

Compost Manure

Dry Seeding

N-use Efficient

Variety (NUE)

Straw Manure

Source: Authors.

Change from Baseline Management

All fertilizer N applied as Ammonium Sulfate

Flood for 3 days every 7 days (3 days flooded, 4 days

drained rotation)

Apply 5,769 kg/ha (3000 kgC/ha) biochar (C:N = 219) at

planting in addition to farmyard manure

Exchange farmyard manure for compost (C:N = 30)

Flood 5 days after planting; flood for approximately 30

days, AWD for approximately 30 days, then flood for

approximately 21 days

Plant tissue C/N (root, stem and leaf, and grain)

increased 25%

Exchange farmyard manure for straw (C:N = 50)

Peanut

Soybean

Maize

Cassava

Sugarcane

-10

-15

Ammonium Sulfate Fertilizer

Biochar

N-use Efficient Variety

Source: Authors.

Table 3: Emission Reduction Potential by crop and mitigation

option

Rice

Peanut

Soybean

Maize

Cassava

Sugarcane

Source: Authors.

Emission Reduction

Potential

81.2

na

8.6

10.4

4.3

8.0

Mitigation Option

AWD or NUE

na

NUE

NUE

NUE

NUE

Costs and Benefits of Implementing Alternative Mitigation Options

Figure 4: Rice AWD: Potential for emission reductions (million tons

CO2e) and income from carbon payments ($/CO2e/ha)

$/ha payment for emission reduction

800

700

600

500

400

300

200

100

0

Tra Vinh

Soc Trang

Bac Lieu

Hau Giang

Ca Mau

Kien Giang

Tien Giang

Ben Tre

Can Tho

Hai Duong

Vinh Long

Ho Chi Minh …

Long An

Dong Thap

Ba Ria-Vung …

An Giang

Binh Phuoc

Hai Phong

Bac Ninh

Dong Nai

Phu Yen

Dac Nong

Binh Dinh

Tay Ninh

Quang Ngai

Quang Nam

Binh Thuan

Khanh Hoa

Binh Duong

Ninh Thuan

Gia Lai

Da Nang

Dak Lak

Lam Dong

Ha Tinh

Kon Tum

Thanh Hoa

Ninh Binh

Ha Tay

Nam Dinh

Hung Yen

Thai Binh

Nghe An

Ha Nam

Ha Noi

Lai Chau

Thua Thien -…

Cao Bang

Quang Binh

Quang Tri

Ha Giang

Dien Bien

Lao Cai

Bac Kan

Son La

Quang Ninh

Vinh Phuc

Yen Bai

Lang Son

Tuyen Quang

Hoa Binh

Bac Giang

Thai Nguyen

Phu Tho

from carbon markets for AWD in rice across the provinces in

Vietnam as well as the total mitigation potential for AWD for each

province. The figure shows that per ha mitigation potential and

thus carbon payments per hectare is lowest in the Mekong Delta

(Tra Vinh, Soc Trang and Bac Lieu) with payments of $12-13 per

hectare rice for AWD and largest in the highland provinces of Thai

Nguyen and Phu Tho with potential payments of $670 and $700. On

the other hand, total mitigation potential for AWD rice is largest in

Bac Giang, Nghe An and Thai Binh provinces and smallest in Dac

Nong.

Given that payments in the major rice-producing areas of

Vietnam would likely be rather modest, it is important that

mitigation activities do not only not compromise crop yields, but

also do not reduce net farm profits, at least not beyond potential

benefits from mitigation.

For Vietnam as a whole, we found that AWD could increase

annual net farm incomes across Vietnam by $41 million from yield

improvements and by a further $627 million from carbon payments

(see Figure 5). Higher net profits from agricultural production are

due to reduced irrigation water applications under this mitigation

option, which more than compensate for slightly lower yields.

Carbon benefits are similarly large for dry seeding ($628 million),

but production benefits are lower (by $247 million) due to lower

crop yields despite cost savings from reduced irrigation applications.

For ammonium sulfate, annual net returns are $431 million for

changes in production and $43 million for changes in emissions.

Applying ammonium sulfate instead of urea results in higher

production costs (40%-increase in fertilizer costs), which is more

than compensated for by higher crop yields.

Figure 5: Changes in net profit (from both agricultural production

and carbon payments), alternative mitigation options, Vietnam

rice area, compared to baseline

Change in benefit from carbon market

Change in benefit from production

2,000

US$ million

1,500

1,000

500

0

AWD

Ammonium

sulfate

Biochar

Compost

manure

Dry seeding

-500

Source: Authors.

5.0

4.0

4.5

3.5

3.0

2.0

2.5

1.5

1.0

0.0

0.5

Total emission reduction (million ton CO2e)

Source: Authors.

Payments from carbon markets for crop-level mitigation are

generally small (for example, $10 per ton carbon sequestered or

emissions reduced). Figure 4 presents the potential per ha payment

Finally, biochar significantly increases crop yields over the 41-year

modeling period, particularly in the Mekong River Delta. Compost

manure is cheaper than farmyard manure but yield declines more

than outweigh benefits from lower production costs. Annual carbon

market benefits of $108 million are insufficient to make up for

income declines from lower production.

No data was available on the increase in net benefits for

increased nutrient-use efficiency, as we assumed this to be achieved

through a new plant variety that is not yet available on the market.

However, the assumption is that increased NUE would reduce costs

through reduced fertilizer application requirements, which is of

great benefit not only to the environment, but also to farmers that

face increasing fertilizer prices as a result of growing oil scarcity.

Carbon market benefits from NUE are estimated at a low $6 million

per year.

increasingly scarce. Similarly, dry-seeding can reduce labor costs

and save irrigation water while reducing GHG emissions.

Figure 6: Poverty concentration (number of people below $2/day

and emissions from staple crops (including all 6 crops studied),

Vietnam

Emissions, Mitigation and Poverty Alleviation

Targeting agricultural mitigation benefits to smallholder farmers

requires to identify those areas that harbor the highest emissions

and highest mitigation potential as well as the largest poverty

concentration.

Figure 6 presents the concentration of poverty and staple crop

emissions across Vietnam. Poverty (number of poor per km2) is

concentrated in the Mekong and Red River Deltas. These same

areas also have the highest GHG emissions, chiefly from rice

production. We also find that the potential for crop-based

mitigation is largest in these two deltas, with small nuances

depending on the mitigation option chosen.

Source: Authors.

Conclusions and Policy Implications

While Vietnam’s emissions are relatively low in a global context,

they are growing rapidly and will likely triple by 2030 unless

significant mitigation options are undertaken.

Agriculture contributes most to GHG emissions in Vietnam, but

the sector will soon be outpaced by emission increases in the

energy sector. Nevertheless, agriculture has an important role to

play in reducing emissions, particularly if smallholder farmers can

obtain economic benefits from implementing emission reductions

by linking to global carbon markets.

Of particular importance, most emission reduction options can

be applied at little cost, lead only to small yield reductions or actual

yield increases, and can help farmers adapt to climate change. AWD,

for example, can save irrigation water and energy use through

reduced pumping; resources that are expected to become

However, the crop-level mitigation potential differs by subregion, mitigation option and crop. While our results need further

study and analysis, they provide a first glimpse at the great variation

across the provinces in Vietnam.

We find that overall the mitigation potential is largest with rice

and largest in those areas that harbor most of the poor people ($2

PPP poverty) in the country.

The importance of agricultural mitigation for Vietnam has been

affirmed by the Government Decision 3119 /QD-BNN-KHCN of Dec

16, 2011, which expressly works toward reducing agricultural

emissions while enhancing economic growth and reducing poverty.

Our analysis has shown that the potential for mitigation is

significant but needs careful assessment regarding yield, production

and other environmental impacts.

William Salas, Changcheng Li, and Pete Ingraham are Vice-President and President at DNDC Applications, Research

and Training and research scientist at Applied GeoSolutions, respectively; Mai Van Trinh is Vice Director at the

Institute for Agricultural Environment; Dao The Anh and Nguyen Ngoc Mai are Director and Senior Researcher,

respectively at Centre for Agrarian Systems Research and Development (CASRAD), Vietnam Academy of Agricultural

Sciences, and Claudia Ringler is a Senior Research Fellow, International Food Policy Research Institute

This project note has been prepared as an output for the “Strategic Partnership to Develop Innovative Policies on

Climate Change Mitigation and Market Access” and has not been peer reviewed. Any opinions stated herein are those of

the authors and do not necessarily reflect the policies or opinions of IFPRI.

Copyright © 2012. International Food Policy Research Institute. All rights reserved. To obtain permission to reprint,

contact the Communications Division at ifpri-copyright@cgiar.org.