Governing the Global Commons

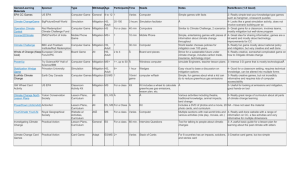

advertisement

Governing the Global Commons Aaron Maltais Department of Government Uppsala University The Card Game • Each player is given two cards: one red and one black • Each player will anonymously hand in one card to the collective pot • Payoff to each student after game play: – 5 kr for a red card in your hand – 1 kr to every player for each red card Center holds • Your task: figure out what to hand in to the collective Public goods and common pool resources Non-rivalrous Rivalrous Public goods Common pool resources Defence, law and order, weather forecasts, benefits Non-excludable associated with reductions of air pollution. Excludable Transboundary ocean fishery, the atmosphere’s protective functions Club goods Private goods Patented knowledge (legal exclusion), cable television (technical exclusion) Food, computers, cars Common Pool Resources Exclusion is impossible or difficult and joint use involves subtractability • Non-Excludability: – Ability to control access to resource – For many global environmental problems it is impossible to physically control access • Subtractability: – Each user is capable of subtracting from general welfare (removing fish from a shared stock or adding pollution to a shared sink) – Inherent to all natural resource use “The Tragedy of the Commons” Article published in 1968 by Garrett Hardin. A shared resource in which any given user reaps the full benefit of his/her personal use, while the losses are distributed amongst all users. If there is open access to the resource the result of individual rational choices is a collective tragedy of unsustainable depletion. Reducing GHG concentrations is a public good 1. Non-excludable - every reduction in GHG emissions benefits all people (although not equally due to variation in the impacts of global warming based on location). 2. Non-rivalrous – no individuals enjoyment of the benefits of mitigating global warming subtracts from others individuals enjoyment of the same good. Negative externalities Free-riding The state can: - ensure public financing for national defense by having a systems of taxes, laws and penalties that make non-cooperation unattractive. - limit access to a common pool resource (e.g. fishing quotas). - turn common resources into private property. But all these options are made possible because of the state’s monopoly on political authority within its territory. International Environmental Agreements •Over 900 multilaterals •1500 bilaterals • Do countries behave selfishly and continue to pollute? • Does mutually beneficial cooperation take place between independent states? • What can be done to increase the chances of cooperative behaviour? Oil Pollution at Sea and The International Convention for the Prevention of Marine Pollution (MARPOL) Migratory Ocean Fisheries - International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT) Ozone Depletion without the Montreal Protocol Source: Nasa, http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/IOTD/view.php?id=38685 Projection of real world ozone recovery Source: Nasa, http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/Features/WorldWithoutOzone/page2.php (Perceived) Payoffs to US with and without Montreal Billions of 1985 US$ Montreal Protocol Benefits 3,575 Unilateral Action without Montreal Protocol 1,373 Costs 21 21 Net Benefits 3,554 1,352 Source: USEPA (1988), reproduced in Barrett (1999) 1. Number of actors OZONE DEPLETION GLOBAL WARMING Positive for international cooperation Negative for international cooperation A few key actors and a limited number of industry players Several important actors and virtually all major industries 2. Where damages will be most sever and where mitigation costs will be highest Tend to coincide territorially 3. Timeframe of impacts Near term benefits from mitigation Benefits far off into the future 4. Level of certainty about benefits of mitigation. Exceptionally positive cost/benefit assessments gives us a high level of certainty Less positive CBAs and more modelling uncertainty give much more uncertainty Yes, the United States No 5. Natural Leaders? 6. Technical/Infrastructural complexity and costs Low, known, and inexpensive Tend to diverge territorially High, unknown, and expensive The international process isn’t working • • • • • • • Contentious negotiations Very weak emissions targets Non-participation of many states Lack of enforcement mechanisms Failures to meet targets Non-binding commitments Delaying of meaningful emissions cuts/investments to the future Short timeframe for action: • Delay makes future mitigation efforts much more costly. • Delay locks us into polluting energy structures. • Delay increases the severity of future climate impacts. • Delay increases the risk of nonlinear climate disasters. • Governments will predictably be faced with hard choices about investing in short‐term measures to deal with major climate impacts versus long-term mitigation. • Overshooting safe emissions budgets strengthens preferences for short-term interests over long-term mitigation. What can we do about global warming? Lie about the timing impacts versus the benefits of mitigation or wait for the early climate catastrophes World Government Bottom up: Regional, local, and individual action 1. Number of actors 2. Where damages will be most sever and where mitigation costs will be highest 3. Timeframe of impacts OZONE DEPLETION GLOBAL WARMING Positive for international cooperation Negative for international cooperation A few key actors and a limited number of industry players Tend to coincide territorially Near term benefits from mitigation Several important actors and virtually all major industries Tend to diverge territorially Benefits far off into the future Exceptionally positive cost/benefit assessments gives us a high level of certainty Less positive CBAs and more modelling uncertainty give much more uncertainty 5. Natural Leaders? Yes, the United States No 6. Technical/Infrastructural complexity and costs Low, known, and inexpensive 4. Level of certainty about benefits of mitigation. This is the problem feature we can actively do something about High, unknown, and expensive What really really matters about climate change is • Avoiding delay in emissions reductions • Acting now to demonstrate that high welfare is compatible with rapidly declining GHG emissions The Need for State Leadership • Developing, demonstrating and deploying new low-carbon technologies • The difficulty of addressing an environmental problem need not be that determinative of success or failure. BUT the combination of a hard problem with uncertainty is toxic (Breitmeier, Underdal, and Young, 2009). • In theory the prospects for alternative energy structures are very promising BUT there is extensive uncertainty surrounding practical application (Kannan, 2009, p. 1874). • Current investment in renewable energy averaged 165 billion US dollars per year over the past three years. • The IEA assesses that this amount needs to rise rapidly to 750 billion per year by 2030 and again to US 1.6 trillion per year between 2030 and 2050 (IEA, 2010, p. 523). • What is at stake is the need for a rapid and sustained increase in our efforts by a factor of four to ten over decades. Note that Ostrom’s conditions for voluntary governance are categorically not satisfied in the climate case: (i) use of the resources can be easily monitored (e.g., trees are easier to monitor than fish); (ii) rates of change in resources, resource-user populations, technology, and economic and social conditions are moderate; (iii) communities maintain frequent face-to-face communication and dense social networks—sometimes called social capital—that increase the potential for trust, allow people to express and see emotional reactions to distrust, and lower the cost of monitoring behavior and inducing rule compliance; (iv) outsiders can be excluded at relatively low cost from using the resource; (v) users support effective monitoring and rule enforcement.