7c-Gains-from-Specialization-and-Exchange

advertisement

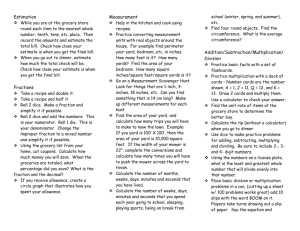

7c The Gains from Specialization and Exchange One approach to illustrating the advantages of specialization in production and exchange is to use wage data. This is simply another way of getting the main point across that people gain from specializing and exchanging. If students get the comparative example from 7b, you may want to stop there. Or, you may want to stick with this approach which avoids the ratios and uses simple multiplication, addition and subtraction. The problem with this approach is that it is not likely to get your students through any common exams. [Optional explanation of the gains from specialization and exchange. Let’s put some numbers on this so we can see the gains from specialization and exchange. Assume that a cabinetmaker is very good at making cabinets and specializes in doing that. She allocates about two hours of her human capital to making a cabinet. Assume further that she averages about $50 per hour making and selling her cabinets. She owns a nice home and has lawns that have to be mowed and leaves and other debris that have to be raked. It would take her about two hours to do the yard work. There is a teenage girl down the street who is very good at mowing lawns and raking yards and she specializes in doing that. She allocates about three hours of her human capital to doing a fair sized yard and she charges $10 per hour. She would like a cabinet for her bedroom and could make it herself. It would take her about 20 hours of human capital. The cabinetmaker is better both at making cabinets and mowing and raking than is the teenager. If the cabinetmaker is better at both activities, is there any way that both the cabinetmaker and the teacher could benefit from specialization and exchange? Should the economics teacher hire the teenager to mow and rake, to make cabinets, both, neither? The question can be answered by answering another question. Even though the cabinetmaker is better at both activities, is she “more better” at one activity than another? Does she have a comparative advantage in one activity? And does the teenager have a comparative advantage in one activity? Cabinetmaker Teenager Cabinetmaker advantage over teenager Teenager disadvantage Hours to Make Cabinet 3 20 Hours to Mow and Rake Yard 2 3 3/20 = .15 2/3 = .67 20/3 = 6.67 3/2 = 1.5 Yes, they do. The cabinetmaker can make a cabinet in 15% of the human capital it takes the teenager to make a cabinet and she can do the yard work with 67% of the human capital it takes the teenager. Her advantage is greater in making cabinets than in doing yard work. She should specialize in cabinets and hire the teenager to do her yard work. She has a greater (or comparative) advantage in cabinets as opposed to yard work. She is “more better” in cabinetmaking than in yard work. But won’t the teenager get ripped off? Well, no actually. The teenager has a smaller disadvantage in yard work (1.5) compared to cabinetmaking (6.67), and so economists say that she has a comparative advantage in yard work. In comparing yard work to cabinetmaking, her disadvantage is smallest in yard work. When discussing comparative advantage, it is important to realize that the comparison is not between the two workers, but between the two activities. Compared to cabinetmaking, the teenager is “less ungood” in yard work. While the language is certainly inelegant, the point is, hopefully, clear. Let’s see who gains when both parties specialize. The table below will help illustrate the situation. This table is based on the assumptions that the cabinetmaker earns $50 per hour and the teenager earns $10 per hour. Cabinetmaker Time to make cabinet Hourly pay Cost to make cabinet Cost to buy cabinet Saving by buying cabinet Time to do yard work Hourly pay Cost to do yard work Cost to buy yard work Saving by buying yard work Teenager 20 hours $10 $200 $150 $50 2 hours $50 $100 $30 $70 Who gains what depends upon the opportunity cost of both individuals. It will cost the cabinetmaker two hours of human capital to mow and rake the lawn. The opportunity cost of using her human capital to do yard work is valued at $100 since she could be using her human capital in those two hours to be making a cabinet. If she hires the teenager, it will cost $30. It is in her best interest to specialize in making cabinets. She is ahead by $70. The teenager could build her own cabinet, but that would take 20 hours of human capital, which is valued at $200. If she buys the cabinet, it will cost $150. It is in the cabinetmaker’s best interest to specialize in cabinets and the teenager’s to specialize in mowing and raking. Even though the cabinetmaker is better at both making cabinets and mowing and raking, because the two have different opportunity costs, it benefits both parties to specialize and exchange. In an exchange between two parties, even if one party is better at both activities, both parties can benefit from specialization and exchange. That is the law of comparative advantage.] In an efficient economy, people become teachers, plumbers, carpenters, engineers or nurses if they have a comparative advantage in that field. The more this rule is followed, the greater the efficiency of the economy and the more goods and services society will produce from its scarce resources