Breaking down silos in seattle*s new stormwater management Plan

advertisement

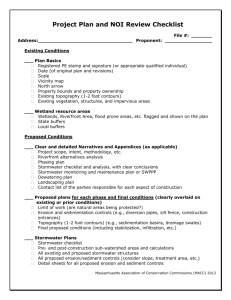

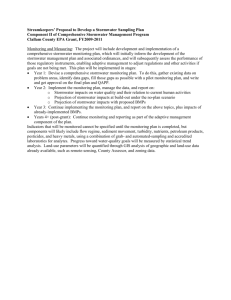

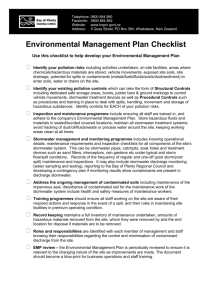

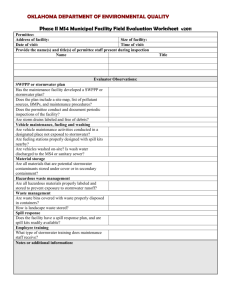

BREAKING DOWN SILOS IN SEATTLE’S NEW STORMWATER MANAGEMENT PLAN By Kelsey Bridges MAY 9, 2014 INFRASTRUCTURE Final Paper Stormwater management planning is best preformed at a regional level due to the large, extensive reach of both natural and manmade water systems. Although, a long term, far reaching management plan is necessary for water management systems, government actors do not always operate in this manner. Silos segregate all sectors of government and can lead to inefficiencies or even mismanagement. The problem of silos is arguably more critical when it comes to infrastructure planning. This field effects local activities but is often planned at a regional level. Projects involving water infrastructure or drainage effect individuals locally but are often envisioned on a larger scale. Due to this span, it becomes even more important to connect to actors across municipalities. Not only do engineers, planners, private actors, public actors, and government officials need to communicate locally, but they need to connect with similar groups in other municipalities. This spring, Seattle’s Mayor, formally announced that the city would be implementing a green stormwater management approach.1 The goal of the city now is to integrate all current and future actors in a comprehensive plan approach. Seattle, like most U.S. cities, has managed its water system through primarily conventional methods. It has recently announced that it will be constructing a master plan that outlines a move to green stormwater infrastructure. However, this is not Seattle’s first green stormwater initiative. It has been incorporating green stormwater infrastructure since the 1990s. Its sewer and drainage systems are primarily combined meaning that when it rains, overflows can occur. This system causes flooding, sewer back-ups, pollution, and combined sewer overflows. Known as a rainy city, it was in 1 http://mayormcginn.seattle.gov/setting-a-new-goal-for-seattles-stormwater-management/ 1 need of improving this stormwater infrastructure, and established projects based on natural drainage systems. In 2004, the city announced a “Restore Our Water’s” Strategy (ROW), which focused on organizing and focusing interest around improving local waterways. It recommended updating stormwater code to include green infrastructure options. Out of this strategy emerged a new Comprehensive Drainage plan that extended stormwater management to incorporate public safety as well as natural resource protection.2 This spring, Seattle announced the creation of a green stormwater management approach that will create a comprehensive plan connecting several of the already existing green infrastructure promoter groups as well as existing design manuals. Although, the city has not had a city wide infrastructure plan, it has supported green infrastructure in its drainage plan which has led to the creation of stormwater design strategy manuals. These manuals have already been used in some roadway projects. For example, the Green Factor program assigns a point system to different landscaping projects that follows green stormwater infrastructure best management practices.3 The city also already has in place a set of green stormwater management incentives. They have rain barrel and cistern rebates as well as a metering system that requires fees for non-residential properties based on the amount of impervious surface on the property. The fees collected from this metering are put toward increasing green stormwater infrastructure.4 These incentives in addition to the design manuals frequently come to fruition after a comprehensive plan has been developed. The 2 http://www.nrdc.org/water/stormwater/files/RooftopstoRivers_Seattle.pdf pg 2 http://www.nrdc.org/water/stormwater/files/RooftopstoRivers_Seattle.pdf pg 1 4 http://www.nrdc.org/water/stormwater/files/RooftopstoRivers_Seattle.pdf pg 1 3 2 reversal of this process makes it easier to create and implement a plan. The GSI Plan’s goal is to manage 700million gallons annually by 2025 through an integrated approach with neighborhood partnering, increasing incentives, using existing GSI manuals, updated stormwater code, and changing land use code.5 Seattle’s stormwater management plan and already existing incentives and guidelines are impressive, but what has helped make all of this possible is the support of green stormwater infrastructure amongst a variety of contributing actors. The city, the county, private actors, public actors, and the community have all worked separately on their own GSI promotion and will now begin working toward the success of a city wide green wastewater infrastructure plan. Not only does the city have a green water infrastructure plan, but King County also has green infrastructure guidelines. In the overview of stormwater flows on the main website, the county recognizes stromwater flows are a source of waterway pollution and can be fixed through reducing impervious surfaces. They also have their own design manual as well as links to rain barrel information, reduced pollution car wash tips, and rain garden plant lists. One of the programs King County promotes that also serves as outreach to the community is their Neighborhood Drainage Assistance Program (NDAP). This program focuses around handling local drainage complaints. If a home or business is seeing damage or inconvenience from flooding, NDAP will assess the problem and address the issue.6 Although this program is unable to address all complaints in a timely manner, it 5 6 http://www.seattle.gov/util/groups/public/@spu/@drainsew/documents/webcontent/01_028902.pdf http://www.kingcounty.gov/environment/waterandland/stormwater/neighborhood-drainage-assistance.aspx 3 serves as a way to connect with the community and educate them on certain GSI designs and solutions. In part due to systems such as NDAP and in part due to other programs and incentives, Seattle has received a lot of public support for GSI. There are also several incentives set in place for obtaining rain barrels or minimizing stromwater runoff. This makes residents aware of the flooding situation as well as aware of ways to minimize flooding and pollution. For example, in 2010, RainWise, an incentive for property owners who install rain gardens or stormwater cisterns was set in place.7 If a home or business is located in a targeted CSO area, the can receive reimbursements for installing a rain garden or swell. City residents are also an active part of the planning and construction process of natural drainage systems. The city has made sure to invite the public to city council and education meetings. This has allowed other actors to contribute to proposed designs. For example, the emergency transportation departments were concerned with access for their vehicles. They attended the meetings and the planners and emergency departments were able to come up with an alternative solution.8 These meetings have encouraged dialogue within the community as well as recognize safety concerns. The University of Washington invested in its own stormwater management program in 2011. Their goals align with the cities stormwater management program. They want to decrease stormwater runoff, flooding, and pollution through green stormwater infrastructure. They have put together several public education and 7 8 http://www.seattle.gov/util/groups/public/@spu/@drainsew/documents/webcontent/01_028902.pdf http://www.nrdc.org/water/stormwater/files/RooftopstoRivers_Seattle.pdf pg 2 4 outreach campaigns to educate the community.9 This outreach will not only be open to students, but the greater Seattle city limits. With the University of Washington providing outreach it will become less necessary for other actors to focus on education and they can focus their efforts elsewhere. Part of this outreach lead to educating and assisting other actors in the community, such as the Port of Seattle. The Port of Seattle of Seattle has also shown support for the citywide plan by implementing some of the proposed processes within their ports. The Port of Seattle serves to coordinate international trade, transportation, commercial fishing, and tourism on the Port of Seattle.10 As a large actor in transportation and water management, the Port’s values on environmental pollution and flooding align with green stromwater infrastructure and they presented a stormwater management program (SWMP) this past spring with assistance from the Washington State Department of Ecology. The Environmental Coalition of South Seattle (ECOSS) has also stepped up as a leader in stormwater research and education. They have advertised themselves as experts in stormwater municipal regulations and pollution. They offer stormwater workshops as well as spill kits for hazardous spills.11 They are a natural ally to the cities GSI goals and have resources, such as the spill kits, that other actors do not, making them an important partner for the city. The city council supports the plan and is already approaching it from an allencompassing viewpoint. “We can’t just focus on doing less harm,” he said. “It’s really time to leverage our stormwater investments to help us with other future-looking goals 9 http://www.ehs.washington.edu/epowaterqual/smpseattle.pdf http://www.portseattle.org/About/Pages/default.aspx 11 http://www.ecoss.org/stormwater.html 10 5 like tree canopy recovery, energy savings, and improving the pedestrian environment of our city. This is a big step in the right direction.”12 The city is looking to public as well as the private sectors to work together to achieve these goals. Each of the above actors supports Seattle’s Green Stormwater management plan individually, but what is also critical is that they have also worked together, breaking down silos. The city has made sure to open up their meetings to the public and the University of Washington has assisted with community outreach as well. The Office of Sustainability and Environment has worked with Seattle Public Utilities in order to create a comprehensive plan that addresses both groups’ goals. Community development agencies have supported the roadside and neighborhood GSI designs that promote traffic calming measures, street beautification, and improved tree canopies. Seattle has also built partnerships financially. Traditionally, capital improvements projects have been funded through the sale of revenue bonds. In 2003, the Seattle Drainage and Wastewater Fund adopted a policy that would allow increasing contributions from Seattle Public Utility, who runs all of the city’s sewage and drainage systems.13 This creates more funding for green infrastructure as well as a relationship between the city of Seattle and the Seattle Public Utility who are working toward the same goals in relation to stormwater management. The partnership created through the city stormwater plan will become increasingly necessary as GSI is implemented throughout the city. There is limited additional funding for these projects even with the Seattle Public Utility’s $35 million, 4 12 13 http://mayormcginn.seattle.gov/setting-a-new-goal-for-seattles-stormwater-management/ http://www.nrdc.org/water/stormwater/files/RooftopstoRivers_Seattle.pdf pg 4 6 year capital improvements budget.14 Funding from all of the above actors, public and private, will be necessary in order to reach the cities 700 million gallon reductions. Although, the above mentioned groups have made a lot of improvements in handling GSI within their own organizations, city and stormwater officials do not think there is enough coordinated efforts between actors which has limited their ability to implement GSI in some areas. With the recent adoption of the city stormwater plan, “a transportation department, for example, will be more inclined to incorporate it when doing road construction, or the parks department might include a green roof or rain garden when designing park improvements.”15 The new plan makes different agencies accountable for reaching specific GSI goals. Infrastructure planning, as with all planning, works best when groups work together to achieve the same goals. Seattle has several actors that have made strides in GSI without an overarching city plan. The next step will be uniting these actors and delegating tasks in order to reach the goals set forth in the stormwater management plan. As the plan moves into fruition, it will be interesting to see how the city organizes itself in order to reach its goals. 14 15 http://daily.sightline.org/2013/04/02/seattles-green-stormwater-goals/ http://daily.sightline.org/2013/04/02/seattles-green-stormwater-goals/ 7 Works Cited "Green Stormwater Infrastructure." (n.d.): n. pag. Seattle.gov, Jan. 2014. Web. <http://www.seattle.gov/util/groups/public/@spu/@drainsew/documents/webcont ent/01_028902.pdf>. Langston, Jennifer. "Seattle’s Green Stormwater Goals." Sightline Daily. N.p., Apr. 2013. Web. 08 May 2014. <http://daily.sightline.org/2013/04/02/seattles-greenstormwater-goals/>. "Seattle, Washington: A Case Study of How Green Infrastructure Is Helping Manage Urban Stormwater Challenges." Rooftops to Rivers, 2010. Web. <http://www.nrdc.org/water/stormwater/files/RooftopstoRivers_Seattle.pdf>. "Stormwater Program." :: Environmental Coalition of South Seattle ::. N.p., n.d. Web. 08 May 2014. <http://www.ecoss.org/stormwater.html>. "Stormwater Services." Neighborhood Drainage Assistance Program (NDAP). King County, n.d. Web. 08 May 2014. <http://www.kingcounty.gov/environment/waterandland/stormwater/neighborhood -drainage-assistance.aspx>. Thomas, April. "Mayor McGinn » Setting a New Goal for Seattle's Stormwater Management." Seattle.gov, Mar. 2014. Web. 08 May 2014. <http://mayormcginn.seattle.gov/setting-a-new-goal-for-seattles-stormwatermanagement/>. 8 "UW Seattle Stormwater Management Program." University of Washington, Mar. 2011. Web. <http://www.ehs.washington.edu/epowaterqual/smpseattle.pdf>. "Where a Sustainable World Is Headed." Port of Seattle, n.d. Web. 08 May 2014. <http://www.portseattle.org/About/Pages/default.aspx>. 9