Aboriginal Issues in 1990s: Enduring Rights and

advertisement

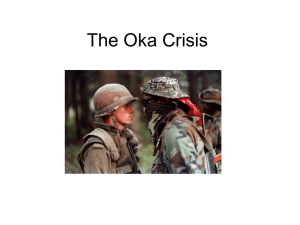

Aboriginal Issues in 1990s: Enduring Rights and Forgotten Claims What do you think are the main reasons why such groups develop anger or resentment against governments or other authorities in society? Why might Canada's First Nations peoples be considered one of these groups with grievances against governments? In the summer of 1990, an area near the Kanesatake Mohawk Reserve in Quebec was slated to be developed into condominiums with a local 9 hole private golf course. This land, recognized as a traditional burial ground, had been claimed by the Mohawk since the 18th century, but land claims were largely ignored. Despite protests by the Mohawk of Kanesatake, and concerns expressed by the Québec Minister of the Environment and Minister of Native Affairs, construction was scheduled to begin, expanding the site to 18 holes and 60 luxury condos. In spite of “Counterpoints: pg 241”, this land was not in fact given to Kanesatake, but is rather owned by the federal government, who is in agreement with Kanesatake on how that land should be used while ongoing negotiations take place. (Source: Aboriginal and Northern Affairs Canada, 2010) What do they think are the main reasons for First Nations resentment? How have aboriginal groups tried to gain attention for their issues, and how successful have they been? Why might such groups sometimes practice dramatic or even illegal actions in order to seek redress for their grievances? Assessing Knowledge Questions: 1) What were the main reasons for the First Nations peoples' resentment against the government in Oka in 1990? 2) How did the Mohawks dramatize their anger and grievances against the government in the actions they took during the summer of 1990? Two stories: 1 Tale 1) Oka Crisis Quebec 2) Marpole Middens Vancouver In your group, you will be required to summarize the position of both parties, answering the following Pre Learning Questions: 1) What are the Acts that regulates aboriginal people in Canada and how is their land managed? 2) How long ago do you feel is “too long” to go back to address past wrongs committed by a society or government? 3) If you were to be found living on aboriginal land and the nation demanded you hand over your property to them, how would you feel? What accommodations could you make, and what would be your course of action? 1) Oka Crisis: The Oka Crisis was a land dispute between the Mohawk nation and the town of Oka, Quebec which began on March 11, 1990, and lasted until September 26, 1990. It resulted in three deaths, and would be the first of a number of well-publicized violent conflicts between Indigenous people and the Canadian Government in the late 20th century. The crisis developed from a dispute between the town of Oka and the Mohawk community of Kanesatake. For 260 years, the Mohawk nation had been pursuing a land claim which included a burial ground and a sacred grove of pine trees near Kanesatake, which is one of the oldest handplanted stands in North America, created by the Mohawks’ ancestors. This brought them into conflict with the town of Oka, which was developing plans to expand a golf course onto the disputed land. In 1717, the governor of New France granted the lands encompassing the cemetery and the pines to a Catholic seminary permission to hold the land in trust for the Mohawk nation. The Church expanded this agreement to grant themselves sole ownership of the land, and proceeded to sell off the Mohawk peoples' land and timber. In 1868, one year after Confederation, the chief of the Oka Mohawk people, Joseph Onasakenrat, wrote a letter to the Church condemning them for illegally holding their land and demanding its return. The petition was ignored. In 1869, Onasakenrat returned with a small armed force of Mohawks and gave the missionaries eight days to return the land. The missionaries called in the police, who imprisoned the Mohawks. In 1936, the seminary sold the remaining territory and vacated the area. These sales were also protested vociferously by the Mohawks, but the protests produced no results. In 1961, a nine-hole golf course, le Club de golf d'Oka, was built on land claimed by the Mohawk People, who launched a legal protest against construction. Yet, by the time the case was heard, much of the land had already been cleared and construction had begun on a parking lot and golf greens adjacent to the Mohawk cemetery. In 1977, the band filed an official land claim with the federal Office of Native Claims regarding the land. The claim was accepted for filing, and funds were provided for additional research of the claim. Nine years later, the claim was finally rejected for failing to meet key criteria. Immediate Causes The mayor of Oka, Jean Ouellette, announced in 1989 that the remainder of the pines would be cleared to expand the members-only golf club's course to eighteen holes. Sixty luxury condominiums were also planned to be built in a section of the pines. The town of Oka stood to make money from the expansion and Mayor Ouellette was a member of the private club that stood to benefit most. However, none of these plans were made in consultation with the Mohawks. As a protest against a court decision which allowed the golf course construction to proceed, some members of the Mohawk community erected a barricade blocking access to the area in question. Mayor Ouellette demanded compliance with the court order, but the protestors refused. Quebec's Minister for Native Affairs John Ciaccia wrote a letter of support for the natives, stating that “these people have seen their lands disappear without having been consulted or compensated, and that, in my opinion, is unfair and unjust, especially over a golf course.” Crisis Despite the letter, the mayor asked the Sûreté du Québec to intervene on July 11, citing Mohawk criminal activity around the barricade. The Mohawk people, in accordance with the Constitution of the Iroquois Confederacy, asked the women, the caretakers of the land and progenitors of the nation, whether or not the arsenal they had amassed should remain. The women decreed that the weapons should be used only if the Sûreté du Québec opened fire first. A police SWAT team swiftly attacked the barricade deploying tear gas canisters and flash bang grenades in an attempt to create confusion in the Mohawk ranks. It is unclear whether the police or Mohawks opened fire with gunshots first, but after a thirty-second firefight the police fell back, abandoning six cruisers and a bulldozer. During the gun battle, 31-year-old Corporal Marcel Lemay of the Sûreté du Québec was shot in the mouth and died a short while later. After the funeral a few days later, the SQ and the Mohawks lowered their flags to half-mast. The Mohawks sent condolences but refused to accept responsibility for the death, blaming Mayor Ouellette for ordering the armed assault on the blockade. Response of White Population Throughout the siege, thousands of white residents of Oka and Chateaguay displayed their racism and hatred of Mohawks. Mohawks were surrounded by white mobs & assaulted. The police barricades became a gathering point for mobs who taunted the warriors, whose positions were a few hundred meters away. They also chanted “Bring in the Army” and “savages.” By August, these gatherings became a daily routine with drinking and partying, & mobs as large as 8,000. At night, effigies of warriors were strung up from lamp posts & burned. By mid-August, white mobs had begun to riot, attacking both SQ & RCMP riot police with rocks, sticks, Molotovs, etc.. In response, Kahnawake prepared for a potential invasion by white mobs as part of its barricade system, which remained on alert throughout the summer. The situation escalated as the local Mohawks were joined by natives from across Canada and the United States. The natives refused to dismantle their barricade and the Sûreté du Québec established their own blockades to restrict access to Oka and Kanesatake. Other Mohawks at Kahnawake, in solidarity with the Kanesatake Mohawks, blockaded the Mercier Bridge between the Island of Montreal and the South Shore suburbs at the point where it passed through their territory. At the peak of the crisis, the Mercier Bridge and highways At the peak of the crisis, the Mercier Bridge and highways 132, 138 and 207 were all blocked. Enormous traffic jams and frayed tempers resulted as the crisis dragged on Musqueam to protest at Marpole Midden Members of the Musqueam First Nation protest a condo development on an ancient burial site on May 3, 2012. (CTV) Vivian Luk, The Canadian Press Published Friday, August 10, 2012 8:01AM PDT VANCOUVER -- Members of an urban Vancouver aboriginal band say they're stepping up their protest to protect a mound of ancient refuse left behind from an aboriginal village nearly 3,000 years ago that, despite its designation as a national heritage site, is at risk of being built over -- again. Members of the Musqueam First Nation say they will block traffic to protest against construction on the Marpole Midden, even though B.C.'s aboriginal relations minister says a cash-for-land deal is close. Mary Polak said Thursday the money offered to the Musqueam should be more than enough for the band to purchase the midden land from the owner who wants to develop the property. In June, the province paid the Musqueam $4.8 million in compensation for one of three pieces of land that are part of major projects such as a new transit line. Polak says the government will offer another $12 million for the remaining two pieces of land, and the money should exceed the midden owner's asking price. But the band, whose members have been protesting against construction on the site ever since human remains were unearthed earlier this year, says the province's cash offer is money owed to the First Nation anyway. "That's our money, that's for other deals that have nothing to do with this, and we are choosing to redirect that money to buy back that land (on Marpole Midden)," band member Rhiannon Bennett told reporters on Thursday. "That is not money they are providing for us out of the goodness of their heart so we can buy the land back." The band had originally wanted to do a land swap to protect the Marpole Midden, but the deal was not signed off. The band also says it wants construction work on the site to stop completely. The Musqueam do not own the land in question, but the midden was designated as a national historic site in 1933. Located at the north arm of the Fraser River, the midden--an archaeological term for the deposits that are left behind by people--contains the remains of a Coast Salish winter village as well as various artifacts from early inhabitants. It was also, at one point, a small pox burial ground, according to Susan Rowley, curator of the University of British Columbia's Museum of Anthropology. Though named a national historic site, the title appears to offer no protection against development. "For a very long time, archaeologists have talked about Marpole as a poster child for an abused archaeological site because of the fact that houses were built there, roads were run through the site in the '20s and '30s, with no care for anything," she said in an interview. The owner of the midden lands and developer Century Holdings intend to build a five-storey commercial and residential complex. Construction was halted briefly in January when the remains of two adults, two babies, and the partial skeleton of another baby were found. Since then, Polak says the permit allowing the developer to dig in the area where the remains were found has been terminated under the provincial Heritage Conservation Act. But a second operating permit for a different area of the site has been extended on a bi-weekly basis while negotiations with the Musqueam band are ongoing. Cecilia Point, a spokeswoman with the Musqueam band, said she believes the permit extensions are a way for the province to appease the developer under the guise of facilitating negotiations. "I think this is also a tactic that the province and developer often use. They think they can wear you out," she said in an interview. "But they're not wearing us out, we have our warrior faces on and we're hitting the ground again 1/8Friday 3/8." Polak says since the land is privately owned and protected by private property laws, the province cannot rescind the operating permit. "The complicating factor here is this isn't Crown land, this is private property," she said. "If you were developing a garage on your property and found remains, you have the right to expect that the law will unfold as it's already laid out." Organization Questions: Prepare a presentation on the article you have read, combined with the viewing of the film. a) Summarize the history of the people and their claim against the government. b) Describe the incident that triggered the event, and what specific action was done by the governments locally and provincially c) How long did this event last, what was the reaction from media, from local non-aboriginal residents? d) What was the end result and what are your feelings? -Elsipogtog First Nation, 2013 Homework: Be prepared next day to summarize (en Francais) one of these events and their current status. 1 Paragraph