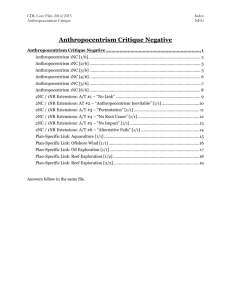

A2 Warming - openCaselist 2012-2013

advertisement