Anthropocentrism Critique Negative

advertisement

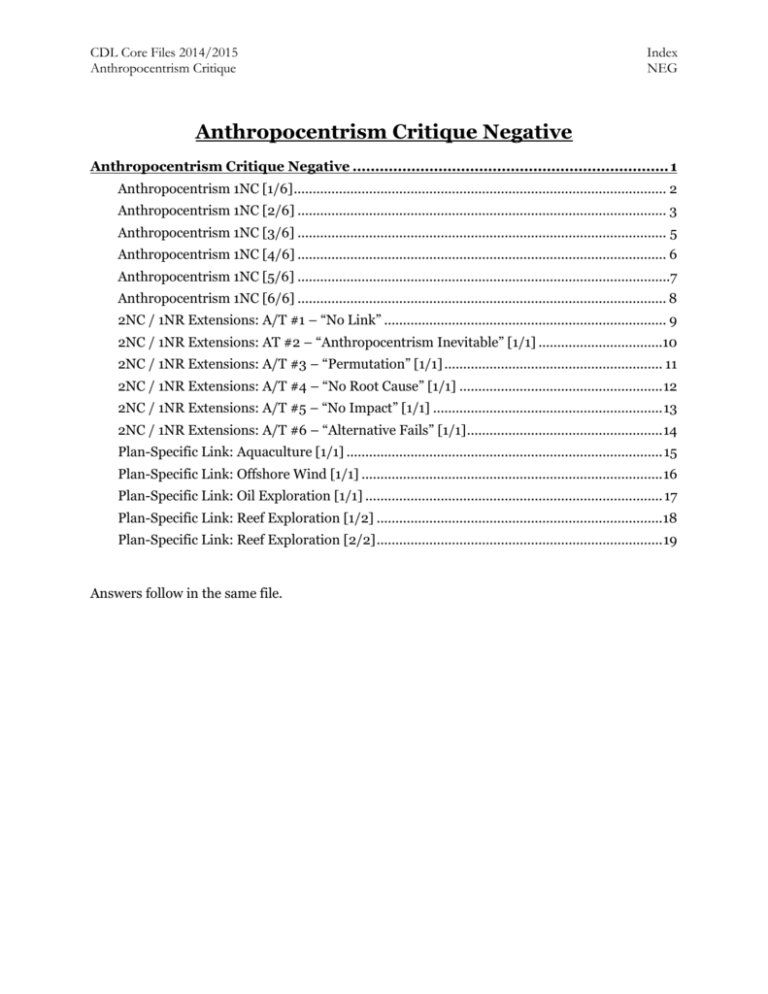

CDL Core Files 2014/2015 Anthropocentrism Critique Index NEG Anthropocentrism Critique Negative Anthropocentrism Critique Negative ...................................................................... 1 Anthropocentrism 1NC [1/6] ................................................................................................... 2 Anthropocentrism 1NC [2/6] .................................................................................................. 3 Anthropocentrism 1NC [3/6] .................................................................................................. 5 Anthropocentrism 1NC [4/6] .................................................................................................. 6 Anthropocentrism 1NC [5/6] ...................................................................................................7 Anthropocentrism 1NC [6/6] .................................................................................................. 8 2NC / 1NR Extensions: A/T #1 – “No Link” ........................................................................... 9 2NC / 1NR Extensions: AT #2 – “Anthropocentrism Inevitable” [1/1] .................................10 2NC / 1NR Extensions: A/T #3 – “Permutation” [1/1] .......................................................... 11 2NC / 1NR Extensions: A/T #4 – “No Root Cause” [1/1] ...................................................... 12 2NC / 1NR Extensions: A/T #5 – “No Impact” [1/1] ............................................................. 13 2NC / 1NR Extensions: A/T #6 – “Alternative Fails” [1/1] .................................................... 14 Plan-Specific Link: Aquaculture [1/1] .................................................................................... 15 Plan-Specific Link: Offshore Wind [1/1] ................................................................................ 16 Plan-Specific Link: Oil Exploration [1/1] ............................................................................... 17 Plan-Specific Link: Reef Exploration [1/2] ............................................................................18 Plan-Specific Link: Reef Exploration [2/2] ............................................................................ 19 Answers follow in the same file. CDL Core Files 2014/2015 Anthropocentrism Critique 1NC Shell NEG Anthropocentrism 1NC [1/6] A. Link – the affirmative has approached the ocean as something to be explored and developed for the purpose of human expansion. This is fundamentally anthropocentric and risks extinction Sivil 2002k [Richard Sivil studied at the University of Durban Westville, and at the University of Natal, Durban. He has been lecturing philosophy since 1996. “WHY WE NEED A NEW ETHIC FOR THE ENVIRONMENT”, 2000, http://www.crvp.org/book/Series02/II-7/chapter_vii.htm] Three most significant and pressing factors contributing to the environmental crisis are the ever increasing human population, the energy crisis, and the abuse and pollution of the earth’s natural systems. These and other factors contributing to the environmental crisis can be directly linked to anthropocentric views of the world. The perception that value is located in, and emanates from, humanity has resulted in understanding human life as an ultimate value, superior to all other beings. This has driven innovators in medicine and technology to ever improve our medical and material conditions, in an attempt to preserve human life, resulting in more people being born and living longer. In achieving this aim, they have indirectly contributed to increasing the human population. Perceptions of superiority, coupled with developing technologies have resulted in a social outlook that generally does not rest content with the basic necessities of life. Demands for more medical and social aid, more entertainment and more comfort translate into demands for improved standards of living. Increasing population numbers, together with the material demands of modern society, place ever increasing demands on energy supplies. While wanting a better life is not a bad thing, given the population explosion the current energy crisis is inevitable, which brings a whole host of environmental implications in tow. This is not to say that every improvement in the standard of living is necessarily wasteful of energy or polluting to the planet, but rather it is the cumulative effect of these improvements that is damaging to the environment. The abuses facing the natural environment as a result of the energy crisis and the food demand are clearly manifestations of anthropocentric views that treat the environment as a resource and instrument for human ends. The pollution and destruction of the non-human natural world is deemed acceptable, provided that it does not interfere with other human beings. It could be argued that there is nothing essentially wrong with anthropocentric assumptions, since it is natural, even instinctual, to favour one’s self and species over and above all other forms of life. However, it is problematic in that such perceptions influence our actions and dealings with the world to the extent that the well-being of life on this planet is threatened, making the continuance of a huge proportion of existing life forms "tenuous if not improbable" (Elliot 1995: 1). Denying the non-human world ethical consideration, it is evident that anthropocentric assumptions provide a rationale for the exploitation of the natural world and, therefore, have been largely responsible for the present environmental crisis (Des Jardins 1997: 93). Fox identifies three broad approaches to the environment informed by anthropocentric assumptions, which in reality are not distinct and separate, but occur in a variety of combinations. The "expansionist" approach is characterised by the recognition that nature has a purely instrumental value to humans. This value is accessed through the physical transformation of the non-human natural world, by farming, mining, damming etc. Such practices create an economic value, which tends to "equate the physical transformation of ‘resources’ with economic growth" (Fox 1990: 152). Legitimising continuous expansion and exploitation, this approach relies on the idea that there is an unending supply of resources. The "conservationist" approach, like the first, recognises the economic value of natural resources through their physical transformation, while at the same time accepting the fact that there are limits to these resources. It therefore emphasises the importance of conserving natural resources, while prioritising the importance of developing the non-human natural world in the quest for financial gain. The "preservationist" approach differs from the first two in that it recognises the enjoyment and aesthetic enrichment human beings receive from an undisturbed natural world. Focusing on the psychical nourishment value of the nonhuman natural world for humans, this approach stresses the importance of preserving resources in their natural states. CDL Core Files 2014/2015 Anthropocentrism Critique 1NC Shell NEG Anthropocentrism 1NC [2/6] Sivil evidence continues, no text deleted… All three approaches are informed by anthropocentric assumptions. This results in a one-sided understanding of the human-nature relationship. Nature is understood to have a singular role of serving humanity, while humanity is understood to have no obligations toward nature. Such a perception represents "not only a deluded but also a very dangerous orientation to the world" (Fox 1990: 13), as only the lives of human beings are recognised to have direct moral worth, while the moral consideration of non-human entities is entirely contingent upon the interests of human beings (Pierce & Van De Veer 1995: 9). Humanity is favoured as inherently valuable, while the non-human natural world counts only in terms of its use value to human beings. The "expansionist" and "conservationist" approaches recognise an economic value, while the "preservationist" approach recognises a hedonistic, aesthetic or spiritual value. They accept, without challenge, the assumption that the value of the non-human natural world is entirely dependent on human needs and interests. None attempt to move beyond the assumption that nature has any worth other than the value humans can derive from it, let alone search for a deeper value in nature. This ensures that human duties retain a purely human focus, thereby avoiding the possibility that humans may have duties that extend to non-humans. This can lead to viewing the non-human world, devoid of direct moral consideration, as a mere resource with a purely instrumental value of servitude. This gives rise to a principle of ‘total use’, whereby every natural area is seen for its potential cultivation value, to be used for human ends (Zimmerman 1998: 19). This provides limited means to criticise the behaviour of those who use nature purely as a warehouse of resources (Pierce & Van De Veer 1995: 184). It is clear that humanity has the capacity to transform and degrade the environment. Given the consequences inherent in having such capacities, "the need for a coherent, comprehensive, rationally persuasive environmental ethic is imperative" (Pierce & Van De Veer 1995: 2). The purpose of an environmental ethic would be to account for the moral relations that exist between humans and the environment, and to provide a rational basis from which to decide how we ought and ought not to treat the environment. The environment was defined as the world in which we are enveloped and immersed, constituted by both animate and inanimate objects. This includes both individual living creatures, such as plants and animals, as well as non-living, non-individual entities, such as rivers and oceans, forests and velds, essentially, the whole planet Earth. This constitutes a vast and all-inclusive sphere, and, for purposes of clarity, shall be referred to as the "greater environment". In order to account for the moral relations that exist between humans and the greater environment, an environmental ethic should have a significantly wide range of focus. I argue that anthropocentric value systems are not suitable to the task of developing a comprehensive environmental ethic. Firstly, anthropocentric assumptions have been shown to be largely responsible for the current environmental crisis. While this in itself does not provide strong support for the claim, it does cast a dim light on any theory that is informed by such assumptions. Secondly, an environmental ethic requires a significantly wide range of focus. As such, it should consider the interests of a wide range of beings. It has been shown that anthropocentric approaches do not entertain the notion that non-human entities can have interests independent of human interests. "Expansionist", "conservationist" and "preservationist" approaches only acknowledge a value in nature that is determined by the needs and interests of humans. Thirdly, because anthropocentric approaches provide a moral account for the interests of humans alone, while excluding non-humans from direct moral consideration, they are not sufficiently encompassing. An environmental ethic needs to be suitably encompassing to ensure that a moral account is provided for all entities that constitute the environment. It could be argued that the indirect moral concern for the environment arising out of an anthropocentric approach is sufficient to ensure the protection of the greater environment. In response, only those entities that are in the interest of humans will be morally considered, albeit indirectly, while those entities which fall outside of this realm will be seen to be morally irrelevant. Assuming that there are more entities on this planet that are not in the interest of humans than entities that are, it is safe to say that anthropocentric approaches are not adequately encompassing. Fourthly, the goals of an environmental ethic should protect and maintain the greater environment. It is clear that the expansionist approach, which is primarily concerned with the transformation of nature for economic return, does not meet these goals. Similarly, neither does the conservationist approach, which is arguably the same as the expansionist approach. The preservationist approach does, in principle satisfy this requirement. However, this is problematic for such preservation is based upon the needs and interests of humans, and "as human interests and needs change, so too would human uses for the environment" (Des Jardins 1997: 129). Non-human entities, held captive by the needs and interests of humans, are open to CDL Core Files 2014/2015 Anthropocentrism Critique 1NC Shell NEG whatever fancies the interests of humans. In light of the above, it is my contention that anthropocentric value systems fail to provide a stable ground for the development of an environmental ethic. CDL Core Files 2014/2015 Anthropocentrism Critique 1NC Shell NEG Anthropocentrism 1NC [3/6] B. Impact – anthropocentrism drives endless consumption that results in ecological destruction Ahkin 2010 [Mélanie, Monash University, “Human Centrism, Animist Materialism, and the Critique of Rationalism in Val. Plumwood’s Critical Ecological Feminism,” Emergent Australasian Philosophers, 2010, Issue 3, http://www.eap.philosophy-australia.com/issue_3/EAP3_AHKIN_Human_Centrism.pdf] These five features provide the basis for hegemonic centrism insofar as they promote certain conceptual and perceptual distortions of reality which universalise and naturalise the standpoint of the superior relata as primary or centre, and deny and subordinate the standpoints of inferiorised others as secondary or derivative. Using standpoint theory analysis, Plumwood’s reconceptualisation of human chauvinist frameworks locates and dissects these logical characteristics of dualism, and the conceptual and perceptual distortions of reality common to centric structures, as follows. Radical exclusion is found in the rationalist emphasis on differences between humans and non-human nature, its valourisation of a human rationality conceived as exclusionary of nature, and its minimisation of similarities between the two realms. Homogenisation and stereotyping occur especially in the rationalist denial of consciousness to nature, and its denial of the diversity of mental characteristics found within its many different constituents, facilitating a perception of nature as homogeneous and of its members as interchangeable and replaceable resources. This definition of nature in terms of its lack of human rationality and consciousness means that its identity remains relative to that of the dominant human group, and its difference is marked as deficiency, permitting its inferiorisation. Backgrounding and denial may be observed in the conception of nature as extraneous and inessential background to the foreground of human culture, in the human denial of dependency on the natural environment, and denial of the ethical and political constraints which the unrecognised ends and needs of non-human nature might otherwise place on human behaviour. These features together create an ethical discontinuity between humans and non-human nature which denies nature’s value and agency, and thereby promote its instrumentalisation and exploitation for the benefit of humans.11 This dualistic logic helps to universalise the human centric standpoint, making invisible and seemingly inevitable the conceptual and perceptual distortions of reality and oppression of non-human nature it enjoins. The alternative standpoints and perspectives of members of the inferiorised class of nature are denied legitimacy and subordinated to that of the class of humans, ultimately becoming invisible once this master standpoint becomes part of the very structure of thought.12 Such an anthropocentric framework creates a variety of serious injustices and prudential risks, making it highly ecologically irrational.13 The hierarchical value prescriptions and epistemic distortions responsible for its biased, reductive conceptualisation of nature strips the non-human natural realm of non- instrumental value, and impedes the fair and impartial treatment of its members. Similarly, anthropocentrism creates distributive injustices by restricting ethical concern to humans, admitting partisan distributive relationships with non-human nature in the forms of commodification and instrumentalisation. The prudential risks and blindspots created by anthropocentrism are problematic for nature and humans alike and are of especial concern within our current context of radical human dependence on an irreplaceable and increasingly degraded natural environment. These prudential risks are in large part consequences of the centric structure's promotion of illusory human disembeddedness, self-enclosure and insensitivity to the significance and survival needs of non-human nature: Within the context of human-nature relationships, such a logic must inevitably lead to failure, either through the catastrophic extinction of our natural environment and the consequent collapse of our species, or more hopefully by the abandonment and transformation of the human centric framework.15 Whilst acknowledging the importance of prudential concerns for the motivation of practical change, Plumwood emphasises the weightier task of acknowledging injustices to non-humans in order to bring about adequate dispositional change. CDL Core Files 2014/2015 Anthropocentrism Critique 1NC Shell NEG Anthropocentrism 1NC [4/6] Ahkin evidene continues, no text deleted… The model of enlightened self-interest implicit in prudentially motivated action is inadequate to this task insofar as it remains within the framework of human centrism. Although it acknowledges the possibility of relational interests, it rests on a fundamental equivocation between instrumental and relational forms of concern for others. Indeed it motivates action either by appeal to humans' ultimate self-interest, thus failing to truly acknowledge injustices caused to non-human others, remaining caught within the prudentially risky framework of anthropocentrism, or else it accepts that others' interests count as reasons for action- enabling recognition of injustices- but it does so in a manner which treats the intersection of others' needs with more fully-considered human interests as contingent and transient. Given this analysis, it is clear that environmental concern must be based on a deeper recognition of injustice, in addition to that of prudence, if it is to overcome illusions of human disembeddedness and self-enclosure and have a genuine and lasting effect. CDL Core Files 2014/2015 Anthropocentrism Critique 1NC Shell NEG Anthropocentrism 1NC [5/6] C. The Alternative – the judge should vote negative to reject the affirmative’s anthropocentric framing. This is vital to re-shape the discussion. Katz and Oechsli 20093 [Members of the Science, Technology, and Society Program,, New Jersey Institute of Technology, Newark. Katz is currently Vice President of the International Society for Environmental Ethics , “Moving beyond Anthropocentrism: Environmental Ethics, Development, and the Amazon.” 1993, http://www.umweltethik.at/download.php?id=392.] Can an environmentalist defend a policy of preservation in the Amazon rain forest without violating a basic sense of justice? We believe that the mistake is not the policy of preservation itself, but the anthropocentric instrumental framework in which it is justified. Environmental policy decisions should not merely concern the trade-off and comparison of various human benefits. If environmentalists claim that the Third World must preserve its environment because of the overall benefits for humanity, then decision makers in the Third World can demand justice in the determination of preservation policy: preservationist policies unfairly damage the human interests of the local populations. If preservationist policies are to be justified without a loss of equity, there are only two possible alternatives: either we in the industrialized world must pay for the benefits we will gain from preservation or we must reject the anthropocentric and instrumental framework for policy decisions. The first alternative is an empirical political issue, and one about which we are not overly optimistic. The second alternative represents a shift in philosophical world view. We are not providing a direct argument for a nonanthropocentric value system as the basis of environmental policy. Rather, our strategy is indirect. Let us assume that a theory of normative ethics which includes nonhuman natural value has been justified. In such a situation, the human community, in addition to its traditional human-centered obligations, would also have moral obligations to nature or to the natural environment in itself. One of these obligations would involve the urgent necessity for environmental preservation. We would be obligated, for example, to the Amazon rain forest directly. We would preserve the rain forest, not for the human benefits resulting from this preservation, but because we have an obligation of preservation to nature and its ecosystems. Our duties would be directed to nature and its inhabitants and environments, not merely to humans and human institutions. From this perspective, questions of the trade-off and comparison of human benefits, and questions of justice for specific human populations, do not dominate the discussion. This change of emphasis can be illustrated by an exclusively human example. Consider two businessmen, Smith and Jones, who are arguing over the proper distribution of the benefits and costs resulting from a prior business agreement between them. If we just focus on Smith and Jones and the issues concerning them, we will want to look at the contract, the relevant legal precedents, and the actual results of the deal, before rendering a decision. But suppose we learn that the agreement involved the planned murder of a third party, Green, and the resulting distribution of his property. At that point the issues between Smith and Jones cease to be relevant; we no longer consider who has claims to Green’s wallet, overcoat, or BMW to be important. The competing claims become insignificant in light of the obligations owed to Green. This case is analogous to our view of the moral obligations owed to the rain forest. As soon as we realize that the rain forest itself is relevant to the conflict of competing goods, we see that there is not a simple dilemma between Third World develop- ment, on the one hand, and preservation of rain forests, on the other; there is now, in addition, the moral obligation to nature and its ecosystems. When the nonanthropocentric framework is introduced, it creates a more complex situation for deliberation and resolution. It complicates the already detailed discussions of human trade-offs, high-tech transfers, aid programs, debt- for-nature swaps, sustainable development, etc., with a consideration of the moral obligations to nonhuman nature. This complication may appear counterproduc- tive, but as in the case of Smith, Jones, and Green, it actually serves to simplify the decision. Just as a concern for Green made the contract dispute between Smith and Jones irrelevant, the obligation to the rain forest makes many of the issues about trade-offs of human goods irrelevant.12 It is, of course, unfortunate that this direct obligation to the rain forest can only be met with a cost in human satisfaction—some human interests will not be fulfilled. Nevertheless, the same can be said of all ethical decisions, or so Kant teaches us: we are only assuredly moral when we act against our inclinations. CDL Core Files 2014/2015 Anthropocentrism Critique 1NC Shell NEG Anthropocentrism 1NC [6/6] Katz and Oeschsli evidence continues, no text deleted… To summarize, the historical forces of economic imperialism have created a harsh dilemma for environmentalists who consider nature preservation in the Third World to be necessary. Nevertheless, environmentalists can escape the dilemma, as exemplified in the debate over the development of the Amazon rain forest, if they reject the axiological and normative framework of anthropocentric instrumental rationality. A set of obligations directed to nature in its own right makes many questions of human benefits and satisfactions irrelevant. The Amazon rain forest ought to be preserved regardless of the benefits or costs to human beings. Once we move beyond the confines of human-based instrumental goods, the environmentalist position is thereby justified, and no policy dilemma is created. This conclusion serves as an indirect justification of a non anthropocentric system of normative ethics, avoiding problems in environmental policy that a human-based ethic cannot.13 CDL Core Files 2014/2015 Anthropocentrism Critique 2NC / 1NR Extensions NEG 2NC / 1NR Extensions: A/T #1 – “No Link” 1. There is a link – the affirmative values the ocean only insofar as it is valuable to humans. Our 1NC Sivil evidence says this is the same mindset that we use to justify prioritizing human interests above other species and caused the destruction of the ocean in the first place because it. 2. [INSERT PLAN-SPECIFIC LINK] CDL Core Files 2014/2015 Anthropocentrism Critique 2NC / 1NR Extensions NEG 2NC / 1NR Extensions: AT #2 – “Anthropocentrism Inevitable” [1/1] 1. Anthropocentrism is not inevitable. If the judge votes negative to reject humancentric policies like the plan, then policies will be evaluated through a more inclusive decision-making process. Our 1NC Katz and Oechsli evidence says this avoids the policy dilemmas described in their evidence. 2. Even if anthropocentrism is inevitable, the judge has an ethical obligation to reject it. Every meaningful social change in history has started with a small number of people embracing a different way of viewing the world at the personal level. 3. An absolute break with anthropocentrism may be impossible, but voting negative to keep trying is important and sufficient to solve. Jackson 2013 [Zakiyyah Iman. Carter G. Woodson Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Virginia. She is also an assistant professor of English at George Mason University. “Animal: New Directions in the Theorization of Race and Posthumanism.” Feminist Studies, Vol 39 N3. 2013] According toWynter, a mutation at the level of the episteme, one as transformative as that which ushered in the epoch of Foucault’s “man,” is required if knowledge is to break from Man’s cognitive and conceptual structures.28 Some of posthumanism’s earliest critics interjected that the field would benefit from more attentiveness to the politics of gender, race, class, and ability, as they believed that the field had unwittingly reinscribed Western exceptionalism, technological fetishism, and ableism in its embrace of “prosthetically-enhanced futures.”29 It would, however, be a mistake to narrowly interpret such criticism as simply a matter of access and identity, something like “posthumanism for everyone.” To do so would miss the larger point, which concerns posthumanism’s stated promise and even responsibility to break with Enlightenment’s order of consciousness. As Wolfe notes in What Is Posthumanism?, one of the hallmarks of liberal humanism “is its penchant for that kind of pluralism, in which the sphere of attention and consideration (intellectual or ethical) is broadened and extended to previously marginalized groups, but without in the least destabilizing or throwing into radical question the schema of the human who undertakes such pluralization.”30 A call for a transformative theory and practice of humanity should not be mistaken for the fantasy of an absolute break with humanism, which has animated so many “post” moments. Rather, in the best work, the “post” marks a commitment to “work through” that which remains lib- eral humanist about their philosophy. Neil Badmington, in “Theorizing Posthumanism,” makes the latter point, arguing that a rigor- ous posthumanism must strive to reach beyond (liberal) humanism while acknowledging that there is still much (liberal) humanism in the posthumanist landscape to work through.31 While I started this essay by observing the customary practice of placing the works in context of a genealogy, what is truly exciting about this moment in posthumanism is that Seshadri, Lundblad, and Chen are charting a new path for future work rather than reinscribing preexisting par- adigms. All three of these texts produce much enthusiasm in this reader about what is to come for posthumanism. CDL Core Files 2014/2015 Anthropocentrism Critique 2NC / 1NR Extensions NEG 2NC / 1NR Extensions: A/T #3 – “Permutation” [1/1] 1. The permutation doesn’t solve the link – the 1AC was aligned with anthropocentrism since the advantages were framed as benefits to human beings exclusively. If we win our link arguments, you should reject the permutation -there’s no benefit to preferring it over the alternative alone. 2. The permutation proves the link – their willingness to contingently prioritize human interests devolves into self-serving rationalizations for anthropocentric policies. Lupisella and Logsdon 1997 [Mark. Masters of Philosophy at Maryland. And John – director of the Space Policy Institute at George Washington. “Do We Need a Cosmocentric Ethic?” 1997 http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/summary?doi=10.1.1.25.7502] Steve Gillett has suggested a hybrid view combining homocentrism as applied to terrestrial activity combined with biocentrism towards worlds with indigenous life.32 Invoking such a patchwork of theories to help deal with different domains and circumstances could be considered acceptable and perhaps even desirable especially when dealing with something as varied and complex as ethics. Indeed, it has a certain common sense appeal. However, instead of digging deeply into what is certainly a legitimate epistemological issue, let us consider the words of J. Baird Callicott: “But there is both a rational philosophical demand and a human psychological need for a self-consistent and all-embracing moral theory. We are neither good philosophers nor whole persons if for one purpose we adopt utilitarianism, another deontology, a third animal liberation, a fourth the land ethic, and so on. Such ethical eclecticism is not only rationally intolerable, it is morally suspect as it invites the suspicion of ad hoc rationalizations for merely expedient or self-serving actions.”33 CDL Core Files 2014/2015 Anthropocentrism Critique 2NC / 1NR Extensions NEG 2NC / 1NR Extensions: A/T #4 – “No Root Cause” [1/1] 1. Anthropocentrism is the root cause of the harms of the 1AC. Resource depletion, environmental destruction, and climate change are all explained by humanity’s continued willingness to ignore non-human species in the name of human consumption – that’s our 1NC Silva evidence. 2. This is also true of geopolitical conflict. The human/non-human dichotomy trains us to treat others as less-than-human, which is a precondition for war. Kochi 2009 [Tarik Kochi is a Lecturer in Law and International at the University of Sussex. “Species War: Law, Violence and Animals in Law” Culture and the Humanities Vol 5 N3. October 2009 ] In relation to the issue of war/law these two insights can be taken further. I think Foucault’s notion of race war can be developed by putting at its heart the differing historical and genealogical relationships between human and non-human animals. Thus, beyond race war what should be considered as a primary category within legal and political theory is that of species war. Further, the fundamental political distinction is not as Schmitt would have it, that of friends and enemies, but rather, the violent conflict between human and non-human animals. Race war is an extension of an earlier form of war, species war. The friend-enemy distinction is an extension of a more primary distinction between human and non-human animals. In this respect, what can be seen to lay at the foundation of the Law of war is not the Westphalian notion of civil peace, or the notion of human rights. Neither race war nor the friend-enemy distinction resides at the bottom of the Law of war. Rather, what sits at the foundation of the Law of war is a discourse of species war that over time has become so naturalised within Western legal and political theory that we have almost forgotten about it. Although species war remains largely hidden because it is not seen as war or even violence at all it continues to affect the ways in which juridical mechanisms order the legitimacy of violence. While species war may not be a Western monopoly, in this account I will only examine a Western variant. This variant, however, is one that may well have been imposed upon the rest of the world through colonization and globalization. In what will follow I offer a sketch of species war and show how the juridical mechanisms for determining what constitutes legitimate violence fall back upon the hidden foundation of species war. I try to do this by showing that the various modern juridical mechanisms for determining what counts as legitimate violence are dependent upon a practice of judging the value of forms of life. I argue that contemporary claims about the legitimacy of war are based upon judgements about differential life-value and that these judgements are an extension of an original practice in which the legitimacy of killing is grounded upon the valuation of the human above the non-human. Further, by giving an overview of the ways in which our understanding of the legitimacy of war has changed, I attempt to show how the notion of species war has been continually excluded from the Law of war and of how contemporary historical movements might open a space for its possible re-inclusion. CDL Core Files 2014/2015 Anthropocentrism Critique 2NC / 1NR Extensions NEG 2NC / 1NR Extensions: A/T #5 – “No Impact” [1/1] 1. The impact to anthropocentrism is endless consumption that results in extinction. When we prioritize human interests over non-human species, it justifies continual ruthless exploitation of natural resources until no life on the planet is sustainable. Our 1NC Ahkin evidence says anthropocentrism makes non-human interests invisible and makes environmental destruction inevitable. 2. Anthropocentrism risks extinction and should be independently rejected because it’s unethical Gottlieb 20094 [Roger. Professor of Humanities at Worcester Polytechnic. “Ethics and Trauma: Levinas, Feminism, and Deep Ecology” 1994 http://www.crosscurrents.org/feministecology.htm] Perhaps there is in progress another, even more encompassing Death Event, which can be the historical condition for an ethic of compassion and care. I speak of the specter of ecocide, the continuing destruction of species and ecosystems, and the growing threat to the basic conditions essential to human life. What kind of ethic is adequate to this brutally new and potentially most unforgiving of crises? How can we respond to this trauma with an ethic which demands a response, and does not remain marginalized? Here I will at least begin in agreement with Levinas. As he rejects an ethics proceeding on the basis of selfinterest, so I believe the anthropocentric perspectives of conservation or liberal environmentalism cannot take us far enough. Our relations with nonhuman nature are poisoned and not just because we have set up feedback loops that already lead to mass starvations, skyrocketing environmental disease rates, and devastation of natural resources. The problem with ecocide is not just that it hurts human beings. Our uncaring violence also violates the very ground of our being, our natural body, our home. Such violence is done not simply to the other -- as if the rainforest, the river, the atmosphere, the species made extinct are totally different from ourselves. Rather, we have crucified ourselves-in-relation-to-the-other, fracturing a mode of being in which self and other can no more be conceived as fully in isolation from each other than can a mother and a nursing child. We are that child, and nonhuman nature is that mother. If this image seems too maudlin, let us remember that other lactating women can feed an infant, but we have only one earth mother. CDL Core Files 2014/2015 Anthropocentrism Critique 2NC / 1NR Extensions NEG 2NC / 1NR Extensions: A/T #6 – “Alternative Fails” [1/1] 1. The alternative solves – rejecting anthropocentric thought causes us to rethink the value systems we employ in our everyday lives. Our 1NC Katz and Oechsli evidence says rejecting anthropocentrism allows us to move beyond human-centric thought and embrace neutral value systems. 2. Even if rejection is insufficient to solve anthropocentrism, we should still fight against it in every instance. That was our Jackson evidence. 3. Rejection achieves actual change – rejecting the hierarchy between human and nonhuman is a critical first step King 1997 [Roger King is a Ph.D. in Agricultural Economics from the University of Reading in England, where he was on the faculty until resigning He has received multiple fellowships from Yaddo, The MacDowell Colony, and the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts. “Critical Reflections on Biocentric Environmental Ethics: Is It an Alternative to Anthropocentrism?” Space, place, and environmental ethic, pg. 215-216] Without denying that anthropocentrism can become much more environmentally informed and sophisticated, there are still several reasons for suspicion that motivate biocentric ethics. First, it might be argued that without a radical shift in attitudes and beliefs about the value of nonhuman nature, narrowly conceived and short-term human interests will continue to prevail at the expense of the environment. Our sense of difference from and superiority to nonhuman nature is so fundamental to our cultural outlook, it might be argued, that nothing short of a shift to a biocentric standpoint will be sufficient to protect even human needs and interests. From this standpoint, it is essential to develop and adopt a biocentric environmental ethic even in order to promote human rights or preference satisfaction. A second argument is that anthropocentrism simply fails to articulate the experience of many human beings. Just as many men and women care about their fellow human beings, respect human rights, and hope to minimize human suffering, so too they care about what happens to domesticated and wild animals, natural ecosystems, and the planet as a whole. And while some may see their moral concern as entirely derivative from their concern for human beings, in the Kantian fashion, many others value nonhuman nature for its own sake and not for the sake of other human beings. The phenomenological reality of this experience and the potential for expanding it justifies efforts to articulate an environmental ethic that does not ultimately reduce value to some derivative of human rights and preferences. A third argument in favor of abandoning anthropocentric ethics is a practical one. If the goal of public policy is simply the satisfaction of human interests, then the resolution of policy conflicts reduces to a balancing of human rights and utilities. In such circumstances, environmental policy may tend to provide less protection both to nature and to human beings than might have been achieved by a biocentric ethic. Eric Katz and Lauren Oechsli have suggested that if the intrinsic value of nonhumans is granted by the parties in policy conflicts, then resolution of the conflicts will also take into account the consequences for nature." Christopher Stone has defended the idea of granting natural entities legal standing on the grounds that unless the natural entity is represented in court proceedings, it is unlikely to benefit directly from damages awarded or reparations imposed by the courts." In sum, the skepticism about anthropocentrism lies in the concern that the definition of costs and benefits will inevitably skew moral deliberations in a self-serving, anthropocentric direction unless we can develop a satisfactory biocentric environmental ethics. CDL Core Files 2014/2015 Anthropocentrism Critique Plan-Specific Links NEG Plan-Specific Link: Aquaculture [1/1] ( ) Aquaculture is particularly anthropocentric – it prioritizes human consumption above the health of fish population Carroll 2009 [Courtney. College of Arts and Sciences at Boston University. “Fish Farming and the Boundary of Sustainability: How Aquaculture Tests Nature’s Resources” Boston University Journal of the Arts and Sciences, 2009 http://www.bu.edu/writingprogram/journal/past-issues/issue-2/carroll/] The advent of aquaculture has extended the industry of factory farming to earth’s marine and freshwater systems. It has greatly benefited the seafood business and has allowed consumers to have traditionally seasonal fish at any time of the year; however as the aquaculture industry rapidly grows from small scale to large scale, many question its sustainability. While the industry insists that fish farming takes the burden off wild fish stocks, other experts have suggested that the farms actually do more harm than help by increasing the spread of diseases, parasites such as sea lice, and astronomically increasing the level of pollution and waste in the wild ecosystems. In particular, the large scale production of carnivorous fish such as salmon has concerned many environmental groups because it requires much larger amounts of resources than producing other types of fish. Escaped salmon from farms can also adversely affect the genetic variability of wild populations, reducing their ecological resilience. The debate over the sustainability of aquaculture represents the conflict between America’s need to conserve and America’s need to control nature’s resources. Rising evidence suggests that fish farming may end up taxing the environment beyond its capacity if it does not become more ecologically mindful. The ultimate question of the debate remains how far society can push the boundary of sustainability and how far technology can extend the capacity of nature’s resources.¶ Technology optimists believe new innovations can resolve any possible hurdles that may come about with the development of aquaculture. Since 1970, seafood production in the aquaculture industry has increased at an annual rate of 8.8% (Morris et al. 2). As the world population approaches 8 billion, seafood producers have harnessed aquaculture in an effort to fill the gap between population growth and natural seafood production (Molyneaux 28–29). Farmed salmon production amounted to 817,000 tons in 2006 and increased 171 fold since 1980 (Morris et al. 2). While shrimp and oyster farms mainly grew out of developing countries, salmon farming grew out of countries with access to more sophisticated technology including the U.S., Canada, and Europe (Molyneaux 45). Initial assessments of fish farming concluded that all economies had an interest in developing aquaculture. For example, on June 2, 1976 in Kyoto, Japan, an FAO Technical Conference on Aquaculture examined and discussed types of aquaculture, the possible problems such as the risk of disease, and ultimately recommended the expansion of aquaculture, leading to huge investment in the rising industry (Molyneaux 30–31). To technology optimists, the potential rewards of aquaculture seemed infinite, but few stopped to consider possible repercussions to the ecosystem.¶ Some environmental concerns about aquaculture did surface as it began to develop, but any initial fears of ecological impacts did little to inhibit growth of the industry. In 1967 the United States Congress established the Commission on Marine Science, and in 1969 the commission released a report that called for more research on aquaculture. Despite the lack of research, the promise of jobs and food security outweighed any concerns about its effects on the environment, and development continued unabated (Molyneaux 45). In addition, the passage of the U.S. Aquaculture Act in 1980 also helped nurture the development of the aquaculture industry (Molyneaux 46). Fish farming has obvious benefits such as food security and jobs, but these obvious benefits obscure many of the potential problems that could arise in the future.¶ An industry such as aquaculture that does not make efforts to promote sustainability will inevitably run into problems, despite any short term benefits it may give to investors. Salmon farms especially merit concern because to produce predatory fish, companies need to “reduce fish” to produce fish, which essentially turns fish lower on the food chain, such as sardines or anchovies, into feed for farmed salmon (Halweil 5). This process requires a huge amount of resources compared to herbivorous fish, making the salmon industry more vulnerable if supplies become scarce and much more energy intensive. In addition, though the aquaculture business claims that its farms provide necessary food production for society’s growing populations, many estimates show that modern fish farming consumes more fish than it produces (Halweil 18). The question of whether aquaculture provides a sufficient food source for future generations means many companies will lead themselves to failure if they do not manage their resources responsibly. CDL Core Files 2014/2015 Anthropocentrism Critique Plan-Specific Links NEG Plan-Specific Link: Offshore Wind [1/1] ( ) Offshore wind projects are steeped in anthropocentrism – the plan specifically sacrifices bird populations at the altar of human interest Fears 2011 [Darryl, reporter for the Washington Post, “Wind farms under fire for bird kills,” 8/28/2011, The Washington Post, http://www.washingtonpost.com/national/health-science/wind-farms-under-fire-for-birdkills/2011/08/25/gIQAP0bVlJ_story.html] Six birds found dead recently in Southern California’s Tehachapi Mountains were majestic golden eagles. But some bird watchers say that in an area where dozens of wind turbines slice the air they were also sitting ducks. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is investigating to determine what killed the big raptors, and declined to divulge the conditions of the remains. But the likely cause of death is no mystery to wildlife biologists who say they were probably clipped by the blades of some of the 80 wind turbines at the three-year-old Pine Tree Wind Farm Project, operated by the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power. As the Obama administration pushes to develop enough wind power to provide 20 percent of America’s energy by 2030, some bird advocates worry that the grim discovery of the eagles this month will be a far more common occurrence. Windmills kill nearly half a million birds a year, according to a Fish and Wildlife estimate. The American Bird Conservancy projected that the number could more than double in 20 years if the administration realizes its goal for wind power. The American Wind Energy Association, which represents the industry, disputes the conservancy’s projection, and also the current Fish and Wildlife count, saying the current bird kill is about 150,000 annually. Over nearly 30 years, none of the nation’s 500 wind farms, where 35,000 wind turbines operate mostly on private land, have been prosecuted for killing birds, although long-standing laws protect eagles and a host of migrating birds. If the ongoing investigation by the Fish and Wildlife Service’s law enforcement division results in a prosecution at Pine Tree, it will be a first. The conservancy wants stronger regulations and penalties for the wind industry, but the government has so far responded only with voluntary guidelines. “It’s ridiculous. It’s voluntary,” said Robert Johns, a spokesman for the conservancy. “If you had voluntary guidelines for taxes, would you pay them?” The government should provide more oversight and force operators of wind turbines to select sites where birds don’t often fly or hunt, the conservancy says. It also wants the wind industry to upgrade to energy-efficient turbines with blades that spin slower. The lack of hard rules has caused some at the conservancy to speculate that federal authorities have decided that the killing of birds — including bald and golden eagles — is a price they are willing to pay to lower the nation’s carbon footprint with cleaner wind energy. But federal officials, other wildlife groups and a wind-farm industry representative said the conservancy’s views are extreme. Wind farms currently kill far fewer birds than the estimated 100 million that fly into glass buildings, or up to 500 million killed yearly by cats. Power lines kill an estimated 10 million, and nearly 11 million are hit by automobiles, according to studies. “The reality is that everything we do as human beings has an impact on the natural environment,” said John Anderson, director of siting policy for the wind-energy association. Another reality is that some wind farms are far more deadly to birds and wildlife than others. One of the nation’s largest wind farms, the Altamont Pass Wind Resource Area near Livermore, Calif., has killed an average of nearly 2,000 raptors annually, including more than 500 eagles, over four years, according to federal agencies and bird watchers. Developers in the early 1980s placed the farm’s 5,000 turbines in an area where several species of raptors hunt. The blades of the early model turbines spin faster to generate power. Critics say it was a blender that cut down birds as they focused on prey. NextEra Energy Resources, which operates the farm, resisted demands to upgrade and relocate equipment for years until its opponents seemed to be on the verge of prevailing in court. It recently settled a lawsuit filed by the Marin Audubon Society and other interest groups and is now making changes that officials say other operators should notice. They include retrofitting and replacing fast-moving turbines with new turbines that generate energy more efficiently with slower-moving blades. Anderson defended Altamont, saying it was built at a time when developers were ignorant about siting and animal habitats. Wind farms get more publicity than other things that cause bird deaths because the birds die where they’re struck, Anderson said. Cars hit them and drive away. And birds fly away from mountaintop mining operations that create conditions that can lead to their demise. A Fish and Wildlife Service official said that there’s no doubt that birds will continue to be killed by wind turbines as they proliferate on land and water, but the trick is to work with the industry to decrease the number of deaths. CDL Core Files 2014/2015 Anthropocentrism Critique Plan-Specific Links NEG Plan-Specific Link: Oil Exploration [1/1] ( ) Oil drilling is an environmental disaster – it destroys marine ecosystems in the name of the fossil fuel economy Hong and Yangie 2009 [Mei Hong and Yin Yangie. Law and Political Science at the University of China’s School of Engineering and Arts Qindao Technical College. “Studies on marine oil spills and their ecological damage” The Journal of Ocean University of China, Feb 2009. Available via SpringerLink] The sources of marine oil spills are mainly from accidents oil marine oil tankers or freighters, marine oildrilling platforms, marine oil pipelines, marine oilfields. terrestrial pollution, oil-bearing atmosphere. and offshore oil production equipment. It is concluded upon analysis that there are two main reasons for marine oil spills: (I) The motive for huge economic benefits of oil industry owners and oil shipping agents far surpasses their sense of ecological risks. (ll) Marine ecological safety has not become the main concern of national security. Oil spills are disasters because humans spare no efforts to get economic benefits from oil. The present paper draws another conclusion that marine ecological damage caused by oil spills can be roughly divided into two categories: damage to marine resource value (direct value) and damage to marine ecosystem service value (indirect value). Marine oil spills cause damage to marine biological. fishery, seawater, tourism and mineral resources to various extents, which contributes to the lower quality and value of marine resources. On May ll, 2006, Solar I, an oil tanker chartered by Petron Corp., the largest oil refinery in the Philippines, sank near Guimaras Island, the Philippines (0CHA-Geneva, 2006). There was about 200000 liters (53000 gallons) of bunker oil in the initial spill. The tanker was sunk in deep water. Making recovery unlikely with an additional 1.8 million liters (475000 gallons) of bunker fuel on board. Roughly 320km (200 miles) of coast line was covered in thick sludge. Miles of coral reel‘ were destroyed and I000 hectares (2470 acres) of marine re~ serve badly damaged. Many mangrove trees and coral reef died and about 25000 people were already affected or displaced during the first few days. 'l11is oil spill was. Undoubtedly. a disaster to the marine ecosystem. However, we must be aware that it was just one case. Let us look back on some serious marine oil spills in history: the oil tanker Torrey Canyon spilled oil; the oil tanker Amoco Cadiz caused leakage (Black-tides, 2008) ; the drilling platform Well lxtoc I Well exploded after catching fire and caused the oil well's blowout: (Office of Response and Restoration, 2007) Exxon Valdez grounded and spilled oil; the oil tanker Prestige wrecked and caused leakage; the oil tanker Tasman Sea spilled oil; BP shutdown the Prudhoe Bay oil field due to a spill from an oil transit line (Blanca cl aI., 2006). It is necessary for us to find out the reasons of oil spills that have frequently occurred for half a century. Actually accidents of marine oil tankers or freighters, marine oildrilling platforms, marine oil pipelines, marine oilfields, fuel leakages, vessels sinking, marine oil exploration and exploitation, operations at ports or quays and operations of offshore and coastal installations can all cause serious damage to the marine ecosystem and have become the main reasons for threatening marine ecological safety (Baker ct aI., 1993). It is essential to identify the sources of marine oil spills, make a profound analysis of the basic reasons, and illustrate the marine ecological damage caused by oil spills (Si, 2002). CDL Core Files 2014/2015 Anthropocentrism Critique Plan-Specific Links NEG Plan-Specific Link: Reef Exploration [1/2] ( ) The affirmative’s fixation with policy solutions means their value structure is rooted in anthropocentrism Katz and Oechsli 20093 [Members of the Science, Technology, and Society Program,, New Jersey Institute of Technology, Newark. Katz is currently Vice President of the International Society for Environmental Ethics , “Moving beyond Anthropocentrism: Environmental Ethics, Development, and the Amazon.” 1993, http://www.umweltethik.at/download.php?id=392.] It is not surprising that anthropocentric arguments dominate discussions of policy: arguments for environmental preservation based directly on human interests are often compelling. Dumping toxic wastes into a community’s reservoir of drinking water is clearly an irrational act; in such a case, a discussion of ethics or value theory is not necessary. The direct harm to humans engendered by this action is enough to disqualify it from serious ethical consideration. Nevertheless, other actions in the field of environmental policy are not so clear: there may be, for example, cases in which there are competing harms and goods to various segments of the human population that have to be balanced. The method for balancing these competing interests gives rise to issues of equity and justice. In addition, and more pertinent to our argument, are cases in which human actions threaten the existence of natural entities not usable as resources for human life. What reason do we humans have for expending vast sums of money (in positive expenditures and lost opportunities) to preserve endangered species of plants and animals that are literally nonresources?2 In these cases, policies of environmental preservation seem to work against human interests and human good. Anthropocentric and instrumental arguments in favor of preservationist policies can be developed in a series and arranged in order of increasing plausibility. First, it is argued that any particular species of plant or animal might prove useful in the future. Alastair Gunn calls this position the “rare herb” theory. According to this theory, the elimination of any natural entity is morally wrong because it closes down the options for any possible positive use.3 A point frequently raised in discussions of this problem is that the endangered species we are about to eliminate might be the cure for cancer. Of course, it is also possible that it will cause cancer; the specific effects of any plant or animal species might be harmful as well as beneficial. Because we are arguing from a position of ignorance, it is ludicrous to assert either possibility as certain, or to use either alternative as a basis for policy. CDL Core Files 2014/2015 Anthropocentrism Critique Plan-Specific Links NEG Plan-Specific Link: Reef Exploration [2/2] ( ) Human-centric approaches to save the environment are couched in anthropocentrism. The plan might do a bit to help the ocean, but the affirmative’s method is dangerous. Fox 20095 [Warwick Fox, Emeritus Professor of Philosophy, University of Central Lancashire. published widely in environmental philosophy, “toward a transpersonal Ecology”, State University of New York Press, 1995, http://www.sunypress.edu/p-2271-toward-a-transpersonal-ecology.aspx] Moving on to illustrate the assumption of human self-importance in the larger scheme of things, we can see that this assumption shows through, for example, in those prescientific views that saw humans as dwelling at the center of the universe, as made in the image of God, and as occupying a position well above the “beasts” and just a little lower than the angels on the Great Chain of Being. And while the development of modern science, especially the Copernican and Darwinian revolutions, swerved to sweep these views aside – or at least those aspects that were open to empirical refutation – it did no such thing to the human-centered assumptions that underlay these views. Francis Bacon for example, saw science as “enlarging the bounds of Human Empire”; Descartes likewise saw it as rendering us the “masters and possessors of nature.” Approximately three and a half centuries later, Neil Armstrong’s moon walk – the culmination of a massive, politically directed, scientific and technological development effort – epitomized both the literal acting out of this vision of “enlarging the bounds of Human Empire” and the literal expression of its anthropocentric spirit: Armstrong’s moon walk was, in his own words at the time, a “small step for him but a “giant leap for Mankind.” Back here on earth, we find that even those philosophical, social, and political movements of modern times most concerned with exposing discriminatory assumptions have typically confined their interests to the human realm, that is, to issues to do with imperialism, race, socioeconomic class, and gender. When attention is finally turned to the exploitation by humans of the nonhuman world, our arguments for the conservation and preservation of the nonhuman world continue to betray anthropocentric assumptions. We argue that nonhuman world should be conserved or preserved because of its use value to humans (e.g., its scientific, recreational, or aesthetic value) rather than for its own sake or for its use value to nonhuman beings. It cannot be emphasized enough that the vast majority of environmental discussion – whether in the context of public meetings, newspapers, popular magazines, reports by international conservation organizations, reports by government instrumentalities, or even reports by environmental groups – is couched with these anthropocentric terms of reference. Thus even many of those who deal most directly with environmental issues continue to perpetuate, however unwittingly, the arrogant assumption that we humans are central to the cosmic drama; that, essentially, the world is made for us. John Seed, a prominent nonanthrsopocentric ecological activist, sums up the situation quite simply when he writes, “the idea that humans are the crown of creation, the source of all value, the measure of all things, is deeply embedded in our culture and consciousness.” CDL Core Files 2014/2015 Anthropocentrism Critique Index AFF Anthropocentrism Critique Affirmative Anthropocentrism Critique Affirmative ............................................................... 20 2AC Frontline: Anthropocentrism Critique [1/4] .................................................................. 21 2AC Frontline: Anthropocentrism Critique [2/4] ................................................................. 22 2AC Frontline: Anthropocentrism Critique [3/4] ................................................................. 23 2AC Frontline: Anthropocentrism Critique [4/4] ................................................................. 24 CDL Core Files 2014/2015 Topicality AFF 2AC Topicality Frontline: Coral Reefs Affirmative AFF 2AC Frontline: Anthropocentrism Critique [1/4] 1. No link – the 1AC argued that the plan would be a good idea for all of Earth’s inhabitants, not just humans. We are not the type of “human centric framing” their evidence criticizes. 2. Anthropocentrism is inevitable and best for non-human species. Humans possess a rational self-interest that ensures sufficient protection of other species. Hayward 2012 [Timothy. Professor of Politics and IR at the University of Edinburgh. “Anthropocentrism” 2012. http://www.academia.edu/4047179/Anthropocentrism ] Because of this radical asymmetry between moral agents and the rest of nature, it can be argued not only that anthropocentrism is justified, but also that to try and avoid it would be a mistake - both in practice and in principle. It would be a practical mistake since it is natural for members of one species to care about others of their own species: we do not criticise a cat for being cat-centered, so why should we criticise humans for being human-centred in this sense? Just as it would be absurd and unwarranted to think that a wild animal should care about human welfare, so is it to think that humans should direct attention from members of their own species to others. Thus if some cultures have evolved as hunters, for instance, they are not for that reason immoral. More generally, all humans consume other living entities in order to reproduce their bodily existence, and humans in all cultures must use nature in various ways in order to survive. It would also be a principled mistake to try and completely overcome anthropocentrism: for even if one is motivated to care about the fate of nonhuman entities, there are limits to how successful one might be, for there are limits to possible human knowledge of what is really good for them, so that at best one has an unreliable, anthropomorphic, view of their good, and, at worst, such a misguided view that in trying to do good one in fact does unrecognized harm. Rather than try to set the nonhuman world to rights, it may therefore be argued, humans would do better to concentrate on their own moral improvement, recognizing that ethics is a peculiarly human affair, concerned with right human action; if they do this, it might further be argued, they are then liable to do less harm to other beings, but for reasons connected with 6 their own moral development. Thus an argument for anthropocentrism which many take to be decisive is that if humans become truly human-centered - in the sense of making a conscientious effort to understand themselves and their place in the world - this will yield an enlightened self-interest which provides a firmer and more reliable basis for the good treatment of nonhuman beings. Both Aquinas and Kant, for instance, believed that cruelty to nonhumans is wrong because it can foster a habit of cruelty more generally - something that is bad for humans to develop in any circumstances. Relatedly, these days it is argued humans should exercise prudence in the use of natural resources, seek to preserve species, biodiversity, and so on, for reasons that derive from their own enlightened self-interest. In short, humans have to recognize that because they live in on world with the rest of nature, if they make things go badly for its other constituents, things will ultimately go badly for them too. This view, moreover, has motivational advantages compared with attempts to appeal to an altruistic concern for nonhumans 'for their own sake', regardless of their interrelation with humans. CDL Core Files 2014/2015 Topicality AFF 2AC Topicality Frontline: Coral Reefs Affirmative AFF 2AC Frontline: Anthropocentrism Critique [2/4] 3. Permutation: do both – the judge can vote affirmative because the plan is a good idea for the interests of all species. This is best because a discussion of environmental ethics is counterproductive. Light 2002 [Andrew. Professor of Philosophy and Environmental Policy at George Mason. “Contemporary Environmental Ethics: From Metaethics to Public Philosophy” Metaphilosophy, Vol 33 N4. 2002. Available via Ebscohost] Even with the ample development in the field of various theories designed to answer these questions, I believe that environmental ethics is, for the most part, not succeeding as an area of applied philosophy. For while the dominant goal of most work in the field, to find a philosophically sound basis for the direct moral consideration of nature, is commendable, it has tended to engender two unfortunate results: (1) debates about the value of nature as such have largely excluded discussion of the beneficial ways in which arguments for environmental protection can be based on human interests, and relatedly (2) the focus on somewhat abstract concepts of value theory has pushed environmental ethics away from discussion of which arguments morally motivate people to embrace more supportive environmental views. As a consequence, those agents of change who will effect efforts at environmental protection – namely, humans – have oddly been left out of discussions about the moral value of nature. As a result, environmental ethics has been less able to contribute to cross-disciplinary discussions with other environmental professionals (such as environmen- tal sociologists or lawyers) on the resolution of environmental problems, especially those professionals who also have an interest in issues concern- ing human welfare in relation to the equal distribution of environmental goods. But can environmental philosophy afford to be quiescent about the public reception of ethical arguments over the value of nature? The original motivations for environmental philosophers to turn their philosophical insights to the environment belie such a position. Environmental philosophy evolved out of a concern about the state of the growing environmental crisis and a conviction that a philosophical contribution could be made to the resolution of this crisis. If environmental philosophers spend most of their time debating non-humancentered forms of value theory, they will arguably never be able to make such a contribution. CDL Core Files 2014/2015 Topicality AFF 2AC Topicality Frontline: Coral Reefs Affirmative AFF 2AC Frontline: Anthropocentrism Critique [3/4] 4. Anthropocentrism is not the root cause of our harms. It’s impossible to know with certainty why the status quo is unsustainable, but the judge can vote affirmative because the plan is an effective solution. Gat 2009 [Azar. Prof Political Science at Tel Aviv. “So Why Do People Fight? Evolutionary Theory and the Causes of War” The European Journal of International Relations, 2009. Available via Sage] This article’s contribution is two-pronged: it argues that IR theory regarding the causes of conflict and war is deeply flawed, locked for decades in ultimately futile debates over narrow, misconstrued concepts; this conceptual confusion is untangled and the debate is transcended once a broader, comprehensive, and evolutionarily informed perspective is adopted. Thus attempts to find the root cause of war in the nature of either the individual, the state, or the international system are fundamentally misplaced. In all these ‘levels’ there are necessary but not sufficient causes for war, and the whole cannot be broken into pieces.13 People’s needs and desires — which may be pursued violently — as well as the resulting quest for power and the state of mutual apprehension which fuel the security dilemma are all molded in human nature (some of them existing only as options, potentials, and skills in a behavioral ‘tool kit’); they are so molded because of strong evolutionary pressures that have shaped humans in their struggle for survival over geological times, when all the above literally constituted matters of life and death. The violent option of human competition has been largely curbed within states, yet is occasionally taken up on a large scale between states because of the anarchic nature of the inter-state system. However, returning to step one, international anarchy in and of itself would not be an explanation for war were it not for the potential for violence in a fundamental state of competition over scarce resources that is imbedded in reality and, consequently, in human nature. The necessary and sufficient causes of war — that obviously have to be filled with the particulars of the case in any specific war — are thus as follows: politically organized actors that operate in an environment where no superior authority effectively monopolizes power resort to violence when they assess it to be their most cost-effective option for winning and/or defending evolutionshaped objects of desire, and/or their power in the system that can help them win and/or defend those desired goods. 5. Their Impact is non-unique and overstated – consumption is occurring in the status quo and there’s nothing specific about the plan that motivates more of it. The plan is a specific use of the ocean that reverses status quo ecological damage – prefer this to their generic, sweeping descriptions of the affirmative. CDL Core Files 2014/2015 Topicality AFF 2AC Topicality Frontline: Coral Reefs Affirmative AFF 2AC Frontline: Anthropocentrism Critique [4/4] 6. The Alternative Fails – rejecting anthropocentrism is net worse for non-human species and risks extinction. Younkins 2004 [Ed. Professor of Business Administration at Wheeling Jesuit. “The Flawed Doctrine of Nature’s Intrinsic Value” Quebecois Libre, 2004. http://www.quebecoislibre.org/04/041015-17.htm] Environmentalists erroneously assign human values and concern to an amoral material sphere. When environmentalists talk about the nonhuman natural world, they commonly attribute human values to it, which, of course, are completely irrelevant to the nonhuman realm. For example, “nature” is incapable of being concerned with the possible extinction of any particular ephemeral species. Over 99 percent of all species of life that have ever existed on earth have been estimated to be extinct with the great majority of these perishing because of nonhuman factors. Nature cannot care about “biodiversity.” Humans happen to value biodiversity because it reflects the state of the natural world in which they currently live. Without humans, the beauty and spectacle of nature would not exist – such ideas can only exist in the mind of a rational valuer. These environmentalists fail to realize that value means having value to some valuer. To be a value some aspect of nature must be a value to some human being. People have the capacity to assign and to create value with respect to nonhuman existents. Nature, in the form of natural resources, does not exist independently of man. Men, choosing to act on their ideas, transform nature for human purposes. All resources are [hu]man-made. It is the application of human valuation to natural substances that makes them resources. Resources thus can be viewed as a function of human knowledge and action. By using their rationality and ingenuity, [humans] men affect nature, thereby enabling them to achieve progress. Mankind’s survival and flourishing depend upon the study of nature that includes all things, even man himself. Human beings are the highest level of nature in the known universe. Men are a distinct natural phenomenon as are fish, birds, rocks, etc. Their proper place in the hierarchical order of nature needs to be recognized. Unlike plants and animals, human beings have a conceptual faculty, free will, and a moral nature. Because morality involves the ability to choose, it follows that moral worth is related to human choice and action and that the agents of moral worth can also be said to have moral value. By rationally using his conceptual faculty, man can create values as judged by the standard of enhancing human life. The highest priority must be assigned to actions that enhance the lives of individual human beings. It is therefore morally fitting to make use of nature. Man’s environment includes all of his surroundings. When he creatively arranges his external material conditions, he is improving his environment to make it more useful to himself. Neither fixed nor finite, resources are, in essence, a product of the human mind through the application of science and technology. Our resources have been expanding over time as a result of our ever-increasing knowledge. Unlike plants and animals, human beings do much more than simply respond to environmental stimuli. Humans are free from nature’s determinism and thus are capable of choosing. Whereas plants and animals survive by adapting to nature, [humans] men sustain their lives by employing reason to adapt nature to them. People make valuations and judgments. Of all the created order, only the human person is capable of developing other resources, thereby enriching creation. The earth is a dynamic and developing system that we are not obliged to preserve forever as we have found it. Human inventiveness, a natural dimension of the world, has enabled us to do more with less. Those who proclaim the intrinsic value of nature view man as a destroyer of the intrinsically good. Because it is man’s rationality in the form of science and technology that permits him to transform nature, he is despised for his ability to reason that is portrayed as a corrupting influence. The power of reason offends radical environmentalists because it leads to abstract knowledge, science, technology, wealth, and capitalism. This antipathy for human achievements and aspirations involves the negation of human values and betrays an underlying nihilism of the environmental movement.