Effective Reading

advertisement

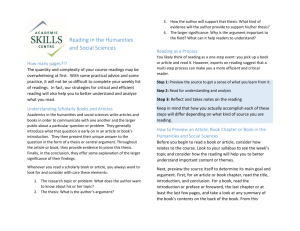

Effective Reading Reading a Secondary Source. Before you can write well, you must read actively. This involves being engaged and aware as you read. Predatory reading, or gutting a book/article involves determining, rapidly, what is most important. The most important component is the argument. So, think logically: in a well-written book or essay, everything serves to further the argument. Look for signposts, or organizational clues. Pay attention to topic sentences (generally the first sentence of each paragraph), which are the minor arguments. Make sure you identify historiographical debates. Look for references to other scholars. Pay attention to the title. What does it mean? Can you predict what the author will cover by reading the title? Read the Table of Contents. What can you expect based on this road map? The forward and introduction are particularly important, so do not skip them. In addition, you may want to read the conclusion before you read the main text. What is the author’s thesis? If you are reading an article, do the same thing—read the first few and last few paragraphs so you can get a sense of the main point or points. Can you determine the structure of the argument? You can read each chapter in a similar manner, by first reading the introduction and conclusion. Going over the introduction and conclusion of each chapter will enable you to quickly determine the books main themes. Reading a history book is not like reading a novel. You do not need to read everything in the order in which it appears. Now you can read the rest of the book. Because you know the main arguments, you can now read the meat of the book and evaluate the evidence. You can read the paragraphs in each chapter in much the same way you started the book. Topic sentences will offer a guide to each paragraph and will tell you which are most important. It can help to take notes. You do not need to take comprehensive notes, but do try to jot down your reactions to the material instead of recording details of the content. Does anything surprise you? Which arguments seem well thought out? Do you think the evidence supports the main themes and arguments? Are there places where the author fails to convince you? Does anything seem to be missing? It can also be useful to take notes at the end of each chapter rather than as a continuous process. What was the main point of the chapter? How did it support the overall thesis? Larger questions you should consider: What is the overarching thesis? In a good history book, everything is included to attempt to prove the thesis. Moreover, an effective writer will state the thesis (or theses) in a clear and obvious manner at the beginning of the book or essay. As you read, you should periodically be able to summarize the main point in a sentence or two. Always asking yourself this question will help you read more actively. A thesis goes beyond stating an opinion. You can evaluate an argument. Is it well conceived? How is the argument broken into major and minor theses? Are the minor arguments well structured? Are the arguments logical? Are the premises and assumptions correct and logical? You need to go beyond evaluating the argument based on whether or not you like it, so think not about your opinion of the argument but about its effectiveness. How is the argument structured and organized? Why did the author organize in this manner? Does the organization enhance or detract from the thesis? What are the author’s motivations and potential biases? Why did the author choose this topic? Is the author responding to other works in the field? When you read an older book, think about the context in which it was written. Historians cannot be completely objective, though that is their intent—they are influenced by the world around them. Political and social events can thus help to explain historical arguments, topics, and works. Do not forget to look at the footnotes! What sources is the author using? Are the sources used effectively? Are there any problems with these particular sources? Are there other sources that could have been employed? To sum up: What does the author say? What are the central questions or problems the author is discussing? What is the explanation? How does the author support their explanation? Why do they say it? Where is the argument weak? If you wanted to challenge this author, how would you do so? What types of primary sources would you search for to challenge the author? What kinds of evidence support the thesis? Why kinds of evidence would undermine the thesis? Reading a Primary Source Reading effectively means constantly asking questions of your sources. You must interrogate your sources. Even if you are confused and unsure of the answers, asking yourself the following questions and going through this process will help you interpret and understand a source. What type of document is it? Who is the author? What is their role? Why was the document created? Was it created for a particular reason? How invested in the text is this author? Why did they write or create the text? What evidence leads you to this position? Is there a thesis? A main point? Argument: A primary source may not have an argument, but it may have a purpose or point. What is the text or author attempting to accomplish? Do they succeed? What is the intended audience? Does this influence the way in which the document is written? Does the author respond to any questions, arguments or concerns that are never clearly stated? Why do you think this is the case? Is the author reliable? Credible? Biased in any way? Assumptions: Do the ideas and values that emerge in the source differ from our own? In what ways? Do our own assumptions or preconceived notions bias how we read the source and react to it? Is there anything that we might find offensive that would not have bothered a person in this time period? Is our understanding of the source potentially biased by different values? Try to avoid being overly presentist by being aware of the ways in which your own values might lead you to misinterpret a source or author. Reading multiple sources: When you have more than one source, it is time to begin to compare them. What patterns do you see emerging in the readings? What are the similarities? What differences do you see? Which ones are more reliable? Less credible? Credibility: Are there reasons to doubt the truthfulness of some sources? Is the author neutral? Does the author have an agenda? Usefulness: What can I learn about the past from this document? In what ways could this document help me formulate an argument?