Across the Atlantic and Back Again: Transnational Narratives of

1

Part I: Preliminary Information

Title: Across the Atlantic and Back Again: Transnational Narratives of Murid Senegalese in

Dakar and New York City

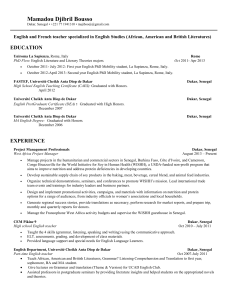

Names: XXXXXXXXXXXXXXX

Abstract:

The Senegalese Murids increasingly live in a transnational space that allows for continued interactions between homeland and diaspora. Working within the relatively new framework of transnationalism, my research examines stories shared in and around this space in order to understand how future and current migrants construct a sense of place in a world where borders are increasingly porous and home is more ideological than geographical. To do so, I will record migration narratives in both Dakar and New York City. The result will be a comparative analysis of how these narratives function personally, socially, economically, and politically, within and outside their communities. My research will contribute significantly to the literature on transnationalism, migration narratives, and community development, and will help to bring voice to the lived experiences of Senegalese Murids. This work will also be relevant for lawmakers, immigration officials, NGOs and, most importantly, Senegalese

Murids at home and abroad.

Personal Statement :

“I was born in Nigeria but I live in Maryland… I’ve been here for 13 years now. My family moved here Christmas Day of 1999. It was the first time I’d seen snow!”

I have often repeated that same snippet of my life—in folklorist Brigitte Boenisch-

Brednich’s terms, the “ready-made” portion of my own migration narrative. If you probed me further, depending on my comfort level, I would briefly explain our reasons for moving. Or I would give you the more detailed response and tell you that my father was a visiting professor at St. Mary’s College in 1995, and while in the U.S., wrote an article about the

Nigerian dictator, General Sani Abacha , making it unsafe for my father to return home. He

2 was granted political asylum in the U.S., and when Abacha died in 1998, my mother, brothers and I joined him in Maryland.

If your interest was piqued, you would ask me more questions and as we spoke, you would notice how my migration narrative never really ended. I’ve been back to Nigeria twice; all my extended family is still there, and I plan to return again. My narrative has now transcended into the realm of transnationalism because I locate home as both here and in

Nigeria. My story functions in many ways, including providing me an avenue to reflect upon my personal and intellectual growth.

From a young age, I was exposed to conversations about major immigration issues, including ‘brain drain’ – the process in which the educated members of a society find occupations elsewhere and are removed from the economy and development of their homeland. The more I learned about it, the more I recognized brain drain as a key deterrent in the advancement of developing countries and did not want to contribute to the phenomenon. Thus, I have devoted myself to learning more about issues affecting developing nations, how diasporas function, and the mutually beneficial methods of self-development between the two.

Arriving at Elon, I quickly declared International Studies and Strategic

Communications majors with an African Studies minor. I sought avenues to participate within the African diaspora community and took courses that would allow me to discover answers to the questions I had about the history and future of Africa. I began volunteering at the Ashton Woods Community Center in Greensboro tutoring refugee children and often wondered about their stories and the potential power of being surrounded by people with similar narratives. On campus, I co-founded the Elon African Society to engage my peers about various African topics that go beyond, and often debunk, the stereotypes perpetuated

by the media. In my honors classes, I undertook extensive research to gain a better understanding of colonization, decolonization, and neo-colonialism and their effects on

Africa today.

Part of my intellectual journey has included talking with and learning from faculty

3 members from departments across the university. During a conversation with Dr. Mould, we discussed the power of narrative to convey perspectives that are rarely addressed explicitly in general discourse. I thought of my own migration narrative and became interested in how other migrants, particularly those in immigrant communities, shaped and utilized their narratives. These conversations, my desire to address pressing issues within and outside of

Africa, and my interest in qualitative fieldwork and inductive research, has led me to my proposed Lumen research project. This project will contribute directly to my goals of conducting graduate work at the School of Oriental and African Studies in London and pursuing my career ambitions of serving as a diplomat or leading an NGO.

Part II: Project Description

Focus:

Touba Qasa’id. Touba Boutique. Matlab al-Fawzayn. Dibiterie Mbacké. Mame Diarra

Fashion. The store names may seem shockingly foreign, but for the Senegalese immigrants in

New York City, they are unequivocal signs of home. The names refer to Murid symbols and convey a shared religious, ethnic and national identity (Kane 2011:70-1). In the heart of

Harlem, the predominantly Wolof-speaking Murid Senegalese migrants have built a community that combines U.S. economic and social practices with Senegalese cultural practices and celebrations. The result is Le Petit Sénégal. 3,800 miles away in Dakar,

Senegal, loved ones are receiving phone calls and money orders from family and friends in

4

New York. Others are preparing to go school abroad, join a loved one abroad, or start an international business, all of which will thrust them into a transnational world.

My research is positioned within the relatively new framework of transnationalism, an approach to understanding globalization that challenges how scholars have thought about ethnic and national enclaves throughout the world. With the aid of Lumen funds, I will conduct ethnographic fieldwork first in Dakar, Senegal and then in Le Petit Sénégal, New

York City. Examining the transnational narratives told by Senegalese people in both locations will address critical issues of community development within transnational communities and thereby aid grassroots organizations that are working to improve the lives of migrants everywhere. My research will address the important dimension of narrative as a significant part in the process of transnationalism, reorienting the focus of migration on the voices of those within these communities in ways that humanize this global issue.

Transnationalism can be understood as the “process by which immigrants forge and sustain multi-stranded social relations that link together their societies of origin and settlement” (Kane 2011: 7, Stone 2005: 382; citing Basch, Schiller and Blanc 1994). Unlike migrants in the period before globalization, today’s migrants are able to keep up significant ties with their country of origin. Previous research identifies ways in which transnational networks aid in development of the homeland (Lacroix 2009) and the diasporic community

(Patterson 2006). Researchers also concentrate on the processes of assimilation and identity reconstruction within the host society (Palmer 2010, Nagel & Staeheli 2005, Abdullah 2012,

Kane 2011). However, the specific narratives people tell in order to verbally construct their social networks and their concepts of home are virtually ignored, a shortcoming made all the more acute by our understanding of the power of narrative in social life.

Compared to discourse more generally, narratives are powerful for their ability to be retold in multiple and disparate contexts, both public and private; their rhetorical power to

persuade; their widespread use in social interactions; and their aesthetic qualities, which make them appealing candidates for frequent performance. In addition, narratives serve not

5 only as a vehicle, but also as an agent, for interpretation (see Bauman 2004, Cashman 2007,

Mould 2011). Accordingly, narrative analysis provides a valuable window into how

Senegalese people—in Dakar and in New York City—actively create, negotiate, and maintain social networks at home and abroad.

While the scholarship on migration narratives remains limited, the majority has tended to focus on political functions (Nagel & Staehali 2006, Shuman & Bohmer 2004) and the maintenance of an ethnic or national identity of the homeland (Palmer 2010). That said, scholars have made some headway into understanding the structures, formulas, and functions of these stories. For example Boenisch-Brednich has identified “ready-mades”—narrative segments that are have been prepared and shared often (2002:70)—while Wolf-Knuts has recognized the prevalence and power of contrast as a common technique in migration narratives (2003). My research will look for similar patterns within the narratives I collect, adding to this growing body of scholarship, but also focus on the function of these stories.

My research will focus specifically on the Murids—an order of Sufism—who have created vibrant migrant communities in both Dakar and New York City. Since 1912,

Senegalese Murids migrated to Dakar during the dry season to be street vendors and wage laborers, returning to the countryside as farmers for the rainy season. After WWII, but predominantly during the late 1970s and early 1980s, weather, economic, and legal conditions caused major migrations to the urban centers of Senegal and eventually other parts of the world (Babou 2007, 201-2). In the 1980s, a small number of Murids began emigrating to the U.S. as street vendors and wage laborers. In both Senegal and the U.S., these new migrants established community centers to address the needs of the group (Kane 2011).

The parallels between these two migrant groups provide an excellent case study for comparative analysis. Of the research on migration, none compare narratives told within the

6 homeland versus the host society. Preliminary research suggests this will be an important point of comparison because the perceived wealth of “male migrant traders of the Murid Sufi order” and their actual wealth seem to be inconsistent (Buggenhagen 2001). This implies that the narratives being told to loved ones back home do not match the narratives told in the diaspora.

This line of research is significant for many reasons, including its multifaceted approach to applying narrative theory to migration studies and the comparative analysis that considers fully the multiple geographies of transnationalism. My focus on transnationalism in today’s global economy will be of particular significance to immigration officials, politicians, community development workers, and, of course, the individuals themselves. It is for this final group, the hundreds of thousands of immigrants who hope to build a new and prosperous life for themselves and their families, that this research is particularly important.

By applying narrative analysis to the concept of transnationalism, this research foregrounds the stories of the migrants themselves, providing a more direct, vibrant and visceral voice to our understanding of this important and growing phenomenon.

Proposed experiences:

Since Senegal is a French-speaking nation, I am currently taking French 222.

However, since the population I will be working with predominantly speaks Wolof, I have registered for an intensive 8-week Wolof language program this summer at the University of

Florida that will make me conversational in Wolof. To prepare for my fieldwork, I am taking

Qualitative Research Methods in Anthropology and working with my mentor to develop my specific methodology.

7

In fall 2013, I will live in Dakar and participate in the CIEE Dakar, Senegal Language and Culture program. My coursework will allow me to gain further academic insight into

Senegalese society as well as grapple with historical and current topics in African Studies. In order to fully immerse myself in the culture I will be participating in a homestay. Throughout my time in Senegal, I will be conducting fieldwork through formal and informal interviews and participating in community center events. I will also be working with community leaders to identify multimedia products to return to the community, to ensure my work can be accessed and used by the communities in which I worked.

During spring 2014, I will complete the analysis of my fieldwork and complete the first chapter of my thesis. In summer 2014 I will conduct fieldwork in Le Petit Sénégal in

NYC, mirroring my work in Dakar.

In fall 2014, I will complete the analysis of my data from New York City and write the second and third chapters of my thesis: an analysis of narratives in NYC, and a comparative analysis of the narratives of both cities, answering many of the larger theoretical questions posed within this research. Through Winter Term 2015, I will design the multimedia products for the communities in Dakar and NYC.

In the beginning of spring 2015 I will complete my thesis and the multimedia community products and present my findings at national conferences such as the International

Conference on Migration and Development and NCUR.

Proposed products:

The bulk of my research will be presented in a comprehensive thesis between 60 and

90 pages containing three main chapters. My thesis will be written as a single, coherent study, but I will revise each chapter for individual submission to various journals, such as The

African Anthropologist and Diaspora: A Journal of Transnational Studies . An additional and

8 crucial part of my work is the multimedia product or products I develop in collaboration with community members. These may include brochures, a website, a book of people’s stories or audiovisual documentation of my research. In this way, I will be producing materials for academic as well as local communities, helping to ensure that my research contributes to current dialogues and discourses that address both theoretical as well as practical issues facing people today.

Part III: Feasibility

Feasibility statement :

Academically and logistically, I have begun to take all the necessary steps to ensure that my Lumen project is entirely feasible. Although my research will be interdisciplinary, I have taken relevant courses, and I have incredible support to ensure that my methodology produces high quality results. Fall semester of my freshmen year, I took Introduction to

Cultural Anthropology with Anne Bolin and I am currently enrolled in Qualitative Research

Methods in Anthropology and Sociology with Mussa Idris. Both courses have taught valuable theories and methods in anthropology and have given me foundational skills in conducting interviews and general ethnographic research. Last semester, I took Communication Research with Lee Bush and had ample practice in conducting focus groups. In addition, I am working closely with Dr. Mould, to develop skills in the elicitation and analysis of narratives from both anthropological and folkloristic perspectives.

The communication classes required for my major (i.e. Digital Media Convergence,

Interactive Media, and Web Publishing) will give me the skills needed to ensure that the multimedia component of my research project is strong and effectively communicates with multiple, diverse audiences. Courses such as Public Relations & Civic Responsibility,

Strategic Writing and my Communications Capstone will allow me to address the needs of

the communities I work with to ensure I leave them a product that will fulfill their expectations of a partnership with me.

I will complete an IRB in order to ensure that my research is valid and follows all proper protocols required. The CIEE program shares space with L'Institut Supérieur de Droit

9 de Dakar (ISDD). Although international lists compiled for researchers in the U.S. suggest there are no specific IRB protocols for Senegal, I will inquire with the faculty at ISDD to make sure this is the case. If there are additional IRB protocols, or the equivalent, I will work with my mentor and the faculty at ISDD to ensure my work meets these standards.

My work in Senegal will be facilitated by formal and informal relationships that I have cultivated. Elon University works closely with its affiliate institution in the city, CIEE, to ensure students are getting the most out of their study abroad experience, through orientations, excursions, high quality faculty members, and a full time support staff. Although

CIEE only offers beginner Wolof classes (and I will have attained Intermediate Wolof proficiency through the University of Florida by the time I arrive in Senegal), Paul Geis in the Global Education Center has confirmed that I will be able to take individual Wolof classes through the Baobab Center. The Center offers individual Wolof lessons to researchers, students, diplomats and anyone else seeking proficiency at any level. These courses, along with my French training, will ensure that I am conversational in both languages; therefore, I will have no trouble conducting my research. Both programs offer homestay services, and if I am successful in receiving the Boren Scholarship, I will be able to arrive early and stay a month longer than the CIEE program. While this extension will be beneficial to my research, it is not a required aspect, so even if I do not get the Boren scholarship, I will still be able to conduct the research I have set out to do.

I am confident I will be able to gain access into the various communities I am proposing to work within. Elon Anthropology faculty member, Mussa Idris, introduced me to

his colleague at Washington University in St. Louis, Dr. Samba Diallo, who is a Senegalese

10 professor in the Department of African and African American Studies. Dr. Diallo, who has written a formal letter of support for my research (enclosed), will be helping me make connections both in Dakar and New York City, including connecting me with his brother, who resides in Dakar and can introduce me to many other useful people in the city.

Budget:

Wolof Classes at the University of Florida - $6,385 o Beginning Wolof 1 & 2 - $4,715 o Room & Board - $1,670

Travel to Senegal - $1,950 o Wolof Classes at the Baobab Center - $450 o Transportation (round trip and on ground) - $1500

Digital Camera and Accessories -- $850 o Canon EOS Rebel T4i 18.0 Digital Camera with 18-135mm Lens ($760) o Two 16 GB San Disk SD cards ($40) o Comos Camera Bag and Shoulder Strap ($50)

Digital Voice Recorder and Accessories -- $175 o Sony Digital Flash Voice Recorder ($125) o Sony Omnidirectional Microphone ($40) o Compact Carrying Case ($10)

Data Storage -- $100 o WD My Passport 1TB ($90) o Case Logic Hard Drive Case ($10)

Lodging in New York Summer 2014 -- $3,463 o 2 Months at International House – $3,040 o Dining Service Fee - $274 o Technology Fee - $84 o Application Fee - $65

Conferences -- $595 o American Folklore Society Annual Meeting

Conference Fees ($95)

Travel and Lodging ($500)

Interviewee Incentives - $600 o Approximately 20 people in Dakar ($10 p/p) - $200 o Approximately 20 people in New York City ($20 p/p) - $400

Transcription Fees: $800

Books: $82

Total : $15,000

11

Timeline:

Summer 2013

Fall 2013

Winter 2014

Spring 2014

Summer 2014

Fall 2014

Winter 2015

Proposed Experiences

Take Wolof classes through

African Language Initiative at the University of Florida

Propose Honors Thesis

Study Abroad in Senegal

Wolof classes at the

Baobab Center

Academic courses, excursions and homestay through CIEE

Record narratives about migration in Dakar

Home Stay & and independent study in Senegal through

Baobab Center

Continue to record narratives

Begin sending audio and video to be transcribed

(4 Research credit hours)

Analysis of narratives and refining of methodology for summer fieldwork

Present on SURF day

Fieldwork in Le Petit Sénégal in

Harlem, New York City

Record narratives

Begin analysis of data

Develop working relationship with a community center in Le

Petit Sénégal

(2 Research Credit Hours)

Write chapters 2 and 3 of my thesis

Design multimedia piece for the communities I worked with

Begin pulling together full draft of thesis

Proposed Products

Become conversational in Wolof

Develop contacts in Senegal

Refine methodology

Ability to function comfortably in

French and Wolof

Intellectual and practical knowledge of Senegalese culture and society

Compile raw data including photos, audio recordings, videos, and field notes

Complete first chapter of my thesis

Compile raw data, photos, videos, audio, field notes

Better understanding of the lived experiences of Senegalese migrants in New York

Complete chapter 2 and 3 of my thesis

Layout of the multimedia community product

12

Spring 2015 (2 Research Credit Hours)

Finish entire thesis

Complete multimedia community product

Present at conferences

Take Communications Capstone and finish the community product as my Strategic

Communications senior project

Honors Thesis Defense

Honors Thesis

Three standalone articles to submit for publication in academic journals

Community product

List of sources:

Abdullah, Zain. 2012. Translation and the Politics of Belonging: African Muslim Circuits in

Western Spaces. Journal of Muslim of Muslim Minority Affairs 32 (4) 427-449

Babou, Cheikh Anta. 2007. Urbanizing Mystical Islam: making Murid Space in the Cities of

Senegal. The International Journal of African historical Studies 40 (2) 197-223

Boenisch-Brednich, Brigitte. 2002. Migration and Narration. Folklore 20: 64-77

Buggenhagen, Beth Anne. 2001. Prophets and Profits: Gendered and Generational Visions of

Wealth and Value in Senegalese Murid Households. Journal of Religion in Africa 31

(4) 373-401

Kane, Ousmane Oumar. 2011. The Homeland is the Arena: Religion, Transnationalism, and the Integration of Senegalese Immigrants in America. Oxford: Oxford University

Press.

Lacroix, Thomas. 2009. Transnational and Development: The Example of Moroccan Migrant

Networks. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 35 (10) 1665-1678

Mould, Tom. 2011. Still, the Small Voice: Narrative, Personal Revelation, and the Mormon

Folk Tradition. Logan: Utah State University Press

Nagel, Caroline R. and Lynn A, Staeheli. 2006. “We’re Just Like the Irish”: Narratives of

Assimilation, Belonging and Citizenship Amongst Arab-American Activists.

Citizenship Studies 9 (5) 485-498

Palmer, David. 2010. The Ethiopian Buna (Coffee) Ceremony: Exploring the Impact of Exile and the Construction of Identity through Narratives with Ethiopian Forced Migrants in the United Kingdom. Folklore 121: 321-333

Patterson, Rubin. 2006. Transnationalism: Diaspora-Homeland Development. Special Forces

85 (4) 1891-1907

13

Riccio, Bruno. 2001. From ‘ethnic group’ to ‘transnational community’? Senegalese migrants’ ambivalent experiences and multiple trajectories.

Journal of Ethnic and

Migration Studies 27 (4) 583-599

Shuman, Amy and Carol Bohmer. 2004. Representing Trauma: Political Asylum Narrative.

Journal of American Folklore 117(466) 394-414

Stone, Elizabeth; Erica Gomez, Despina Hotzoglou, Jane Y. Lipnitsy. 2005. Transnationalism as a Motif in Family Stories. Family Process 44 (4) 381-398.

Wolf-Knuts, Ulrika. 2003. Contrasts as a Narrative Technique in Emigrant Accounts.

Folklore 114 (2003):91-105