Copyright 1989 Guardian Newspapers Limited

advertisement

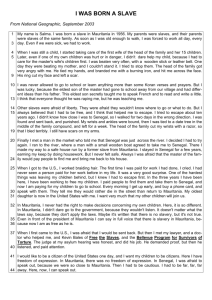

Copyright 1989 Guardian Newspapers Limited The Guardian (London) May 2, 1989 LENGTH: 646 words HEADLINE: Brutal end to Senegal haven BYLINE: By MARK DOYLE DATELINE: DAKAR BODY: The violence that flared in Senegal and Mauritania in the past week, leaving about 250 people dead, came as a surprise to most observers. Although race and colour are a significant factor in Mauritanian politics, Senegal had been thought of as a haven for foreigners - not only Mauritanian Moors but also black Africans from neighbouring countries, as well as Lebanese and Europeans. Before the recent communal violence, Senegal was home for about 300,000 Mauritanians. A much small number of Senegalese - perhaps 30,000 - lived in the more sparsely populated, mostly desert, territory of Mauritania. While white Moors dominate Mauritanian political structures, black Moors also have an elevated position compared with black Africans living there. Slavery was only abolished in Mauritania in 1980 and many black Haratines, as a slaves were known, continue to be bonded labour for mainly white masters. As the tit-for-tat killings in both countries reached their peak at the end of last week, some reports from Nouakchott, the capital of Mauritania, said that groups of Haratines were killing Senegalese on their masters' instructions. In Senegal, the violence was targeted specifically at Mauritianians who control about 80 per cent of petty commerce, making them identifiable and accessible targets, not to say possessers of goods worth plundering. Their shops, often little more than holes in the wall with a metal door, sell sugar, butter and cigarettes in minute quantities to hard-pressed Senegalese who cannot afford to visit the European-style supermarkets frequented by the middle class. As far as Senegalese were concerned, it was Mauritanians who were responsible for the April 9 border grazing rights incident in which Mauritanian guards shot dead two Senegalese peasants. Disputes over grazing rights are common in an area where Mauritanian camels wander at will, oblivious to a border imposed, by the colonial powers and which separates communities arbitrarily. Feelings were inflamed partly because the Senegalese opposition press tried to make political capital out of the incident, accusing President Abdou Diouf of inaction. In the subsequent cycle of murder and looting in Nouakchott and dakar, the capital of Senegal, it is unclear to what extent, it any, the authorities in either country gave a green light for gangs to go on the rampage. Ethnic tension was not limited to the streets. During the killings, the governments of neither country came out with a strong condemnation of the deaths in the opposing community. President Diouf was quick to condemn Senegalese deaths but as of last night he had not expressed regret over the deaths of Mauritanians. For their part, the Mauritanian authorities deplored killing on both sides only after the worst of the violence was over. As for official involvement in the actual killings, President Diouf made references to reports that Mauritanian security forces might have been involved, and that if this were established as fact, his government 'reserved the right to take any necessary measures'. Some reports from Mauritania, as yet unconfirmed, accused members of the Mauritanian police force of being either involved in the killing or allowing it to take place. On the Senegalese side, there were a number of occasions when the security forces stood by while looting and perhaps worse occurred. By midday yesterday, more than 8,000 Senegalese had been airllifted from Mauritania and several thousand Mauritanians had been evacuated home from Senegal. According to sources at Dakar airport, Senegalese customs officers were systematically taking money and valuables from the departing Mauritanians. The customs men said they had official instructions to do this in reprisal for similar seizures from Senegalese refugees leaving Mauritania. LOAD-DATE: June 13, 2000