The Bridge on the River Kwai Film Notes

advertisement

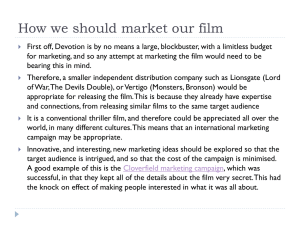

The Bridge on the River Kwai Film Notes The Bridge on the River Kwai Original release poster Directed by David Lean Produced by Sam Spiegel Screenplay by Based on Michael Wilson Carl Foreman The Bridge over the River Kwai by Pierre Boulle William Holden Jack Hawkins Starring Alec Guinness Sessue Hayakawa James Donald Geoffrey Horne Music by Malcolm Arnold Cinematography Jack Hildyard Editing by Peter Taylor Studio Horizon Pictures Distributed by Columbia Pictures Release date(s) 2 October 1957 Running time 161 minutes Country United Kingdom Language English Budget $3 million (estimated) Box office $33.3 million (in U.S.) The Bridge on the River Kwai is a 1957 British World War II film by David Lean based on The Bridge over the River Kwai by French writer Pierre Boulle. The film is a work of fiction but borrows the construction of the Burma Railway in 1942–43 for its historical setting. It stars William Holden, Jack Hawkins, Alec Guinness and Sessue Hayakawa. The movie was filmed in Sri Lanka (credited as Ceylon, as it was known at the time). The bridge in the movie was located near Kitulgala. The film achieved near universal critical acclaim, winning seven Academy Awards, and in 1997, this film was deemed "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant" and selected for preservation in the United States Library of Congress National Film Registry. Plot After the surrender of Singapore in World War II, a unit of British soldiers is marched to a Japanese prison camp in western Thailand. They are paraded before the camp commandant, Colonel Saito (Sessue Hayakawa), who informs them of his rules; all prisoners, regardless of rank, are to work on the construction of a bridge over the River Kwai to carry a new railway line to invade Burma. Their commander, Lt. Colonel Nicholson (Alec Guinness), reminds Saito that the Geneva Conventions exempt officers from manual labour; Saito slaps him hard across the face with his copy of the conventions. At the following morning’s parade, Nicholson orders his officers to remain behind when the enlisted men head off to work. Saito threatens to have them shot, but Nicholson refuses to back down. When Major Clipton (James Donald), the British medical officer, intervenes, Saito leaves the officers standing all day in the intense tropical heat. That evening, the officers are placed in a punishment hut, while Nicholson is locked in ‘the oven’, an iron box, without food or water. Clipton attempts to secure Nicholson's release, but Nicholson refuses to compromise. Meanwhile, the prisoners are working as little as possible and sabotaging whatever they can. Saito is concerned because, should he fail to meet his deadline, he would be obliged to commit seppuku (ritual suicide). Using the anniversary of Japan's great victory in the 1905 RussoJapanese War as an excuse to save face, he gives in, and Nicholson and his officers are released. Nicholson conducts an inspection and is shocked by what he finds. Against the protests of some of his officers, he orders Captain Reeves (Peter Williams) and Major Hughes (John Boxer) to design and build a proper bridge, despite its military value to the Japanese, for the sake of his men's morale. The Japanese engineers had chosen a poor site, so the original construction is abandoned and a new bridge is begun 400 yards downstream. Meanwhile, three prisoners attempt to escape. Two are shot dead, but United States Navy Commander Shears (William Holden), gets away, although badly wounded. After many days, Shears eventually stumbles into a village, whose people help him to escape by a boat. Shears is enjoying his recovery at the Mount Lavinia Hospital at Ceylon (with a pretty British nurse), when Major Warden (Jack Hawkins) asks him to volunteer for a commando mission to destroy the bridge. Shears is horrified at the idea and reveals that he is not an officer at all. He was an enlisted man on the cruiser USS Houston. He switched uniforms with the dead Commander Shears after the sinking of their ship to get better treatment. Warden already knows this and has had "Shears" reassigned to British duty. Faced with the prospect of being charged with impersonating an officer, Shears has no choice but to volunteer; Warden gives him the "simulated rank of major." Meanwhile, Nicholson drives his men, even volunteering to have them work harder to complete the bridge on time. For Nicholson, its completion will exemplify the ingenuity and hard work of the British Army for generations. When he asks that their Japanese counterparts join in as well, a resigned Saito replies that he has already given the order. The commandos parachute in, although one is killed in a bad landing. The other three—Warden, Shears, and Canadian Lieutenant Joyce (Geoffrey Horne)—reach the river with the assistance of Siamese women porters and their village chief, Khun Yai. Warden is wounded in an encounter with a Japanese patrol, and has to be carried on a litter. The trio reach the bridge in time and plant explosives underwater under cover of darkness. A train carrying soldiers and important dignitaries is scheduled to be the first to use the bridge the following morning, so Warden plans to destroy both at the same time. However, by dawn the water level has dropped, exposing the wire connecting the explosives to the detonator. Making a final inspection, Nicholson spots the wire and brings it to Saito's attention to the consternation of the commando team. As the train is heard approaching, Nicholson, with Saito in tow, hurries down to the riverbank to investigate. Joyce, hiding with the detonator, breaks cover and stabs Saito to death; Nicholson yells for help, while attempting to stop Joyce from reaching the detonator. Shears and Warden yell for Joyce to kill Nicholson, but Joyce is killed by Japanese fire. Shears then swims across the river to fulfill the mission, but is shot just before he reaches Nicholson. Recognising the dying Shears, Nicholson exclaims, "What have I done?" Warden fires his mortar, mortally wounding Nicholson. The dazed colonel stumbles towards the detonator and falls on it as he dies, just in time to blow up the bridge and send the train hurtling into the river below. As he witnesses the carnage, Clipton shakes his head uttering: "Madness...Madness." Cast William Holden as US Navy Commander/Seaman Shears Alec Guinness as Lieutenant Colonel Nicholson Jack Hawkins as Major Warden Sessue Hayakawa as Colonel Saito James Donald as Major Clipton Geoffrey Horne as Lieutenant Joyce André Morell as Colonel Hornsby Peter Williams II (actor)|Peter Williams]] as Captain Reeves John Boxer as Major Hughes Percy Herbert as Private Grogan Harold Goodwin as Private Baker Ann Sears as nurse Historical parallels The bridge over the River Kwai in June 2004. The round truss spans are the originals; the angular replacements were supplied by the Japanese as war reparations. The largely fictional film plot is loosely based on the building in 1943 of one of the railway bridges over the Mae Klong—renamed Khwae Yai in the 1960s—at a place called Tha Ma Kham, five kilometres from the Thai town of Kanchanaburi. According to the Commonwealth War Graves Commission: "The notorious Burma-Siam railway, built by Commonwealth, Dutch and American prisoners of war, was a Japanese project driven by the need for improved communications to support the large Japanese army in Burma. During its construction, approximately 13,000 prisoners of war died and were buried along the railway. An estimated 80,000 to 100,000 civilians also died in the course of the project, chiefly forced labour brought from Malaya and the Dutch East Indies, or conscripted in Siam (Thailand) and Burma. Two labour forces, one based in Siam and the other in Burma worked from opposite ends of the line towards the centre."[1] The incidents portrayed in the film are mostly fictional, and though it depicts bad conditions and suffering caused by the building of the Burma Railway and its bridges, historically the conditions were much worse than depicted.[2] The real senior Allied officer at the bridge was British Lieutenant Colonel Philip Toosey. Some consider the film to be an insulting parody of Toosey.[3] On a BBC Timewatch programme, a former prisoner at the camp states that it is unlikely that a man like the fictional Nicholson could have risen to the rank of lieutenant colonel; and if he had, due to his collaboration he would have been "quietly eliminated" by the other prisoners. Julie Summers, in her book The Colonel of Tamarkan, writes that Pierre Boulle, who had been a prisoner of war in Thailand, created the fictional Nicholson character as an amalgam of his memories of collaborating French officers.[3] He strongly denied the claim that the book was anti-British, though many involved in the film itself (including Alec Guinness) felt otherwise.[4] Toosey was very different from Nicholson and was certainly not a collaborator who felt obliged to work with the Japanese. Toosey in fact did as much to delay the building of the bridge as possible. Whereas Nicholson disapproves of acts of sabotage and other deliberate attempts to delay progress, Toosey encouraged this: termites were collected in large numbers to eat the wooden structures, and the concrete was badly mixed.[3][5] Some of the characters in the film have the names of real people who were involved in the Burma Railway. Their roles and characters, however, are fictionalized. For example, a SergeantMajor Risaburo Saito was in real life second in command at the camp. In the film, a Colonel Saito is camp commandant. In reality, Risaburo Saito was respected by his prisoners for being comparatively merciful and fair towards them; Toosey later defended him in his war crimes trial after the war, and the two became friends. The destruction of the bridge as depicted in the film is entirely fictional. In fact, two bridges were built: a temporary wooden bridge and a permanent steel/concrete bridge a few months later. Both bridges were used for two years, until they were destroyed by Allied aerial bombing. The steel bridge was repaired and is still in use today. Production Screenplay The screenwriters, Carl Foreman and Michael Wilson, were on the Hollywood blacklist and could only work on the film in secret. The two did not collaborate on the script; Wilson took over after Lean was dissatisfied with Foreman's work. The official credit was given to Pierre Boulle (who did not speak English), and the resulting Oscar for Best Screenplay (Adaptation) was awarded to him. Only in 1984 did the Academy rectify the situation by retroactively awarding the Oscar to Foreman and Wilson, posthumously in both cases. Subsequent releases of the film finally gave them proper screen credit. The film was relatively faithful to the novel, with two major exceptions. Shears, who is a British commando officer like Warden in the novel, became an American sailor who escapes from the POW camp. Also, in the novel, the bridge is not destroyed: the train plummets into the river from a secondary charge placed by Warden, but Nicholson (never realizing "what have I done?") does not fall onto the plunger, and the bridge suffers only minor damage. Boulle nonetheless enjoyed the film version though he disagreed with its climax. Filming A scene in the film, bridge at Kitulgala in Sri Lanka, before the explosion A photo of Kitulgala in Sri Lanka (photo taken 2004), where the bridge was made for the film. Many directors were considered for the project, among them John Ford, William Wyler, Howard Hawks, Fred Zinnemann and Orson Welles.[citation needed] The film was an international co-production between companies in Britain and the United States. It is set in Thailand, but was filmed mostly near Kitulgala, Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), with a few scenes shot in England. Lean clashed with his cast members on multiple occasions, particularly Alec Guinness and James Donald, who thought the novel was anti-British. Lean had a lengthy row with Guinness over how to play the role of Nicholson; Guinness wanted to play the part with a sense of humour and sympathy, while Lean thought Nicholson should be "a bore." On another occasion, Lean and Guinness argued over the scene where Nicholson reflects on his career in the army. Lean filmed the scene from behind Guinness, and exploded in anger when Guinness asked him why he was doing this. After Guinness was done with the scene, Lean said "Now you can all f--- off and go home, you English actors. Thank God that I'm starting work tomorrow with an American actor (William Holden)."[6] Alec Guinness later said that he subconsciously based his walk while emerging from "the Oven" on that of his son Matthew when he was recovering from polio. He called his walk from the Oven to Saito's hut while being saluted by his men the "finest work I'd ever done."[citation needed] Lean nearly drowned when he was swept away by a river current during a break from filming; Geoffrey Horne saved his life.[citation needed] The filming of the bridge explosion was to be done on March 10, 1957, in the presence of S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike, then Prime Minister of Ceylon, and a team of government dignitaries. However, cameraman Freddy Ford was unable to get out of the way of the explosion in time, and Lean had to stop filming. The train crashed into a generator on the other side of the bridge and was wrecked. It was repaired in time to be blown up the next morning, with Bandaranaike and his entourage present.[citation needed] According to the supplemental material in the Blu-ray digipak, a thousand tons of explosives were used to blow up the bridge. This is highly unlikely, as the film shows roughly 50 kg of plastique being used simply to knock down the bridge's supports. According to Turner Classic Movies, the producers nearly suffered a catastrophe following the filming of the bridge explosion. To ensure they captured the one-time event, multiple cameras from several angels were used. Ordinarily, the film would have been taken by boat to London, but due to the Suez crisis this was impossible; therefore the film was taken by air freight. When the shipment failed to arrive in London, a worldwide search was undertaken. To the producers' horror the film containers were found a week later on an airport tarmac in Cairo, sitting in the hot Egyptian sun. Though it was not exposed to sunlight, the heat-sensitive color film stock should have been hopelessly ruined; however, when processed the shots were perfect and appeared in the film. Music A memorable feature of the film is the tune that is whistled by the POWs—the first strain of the march "Colonel Bogey"—when they enter the camp.[7] The march was originally written in 1914 by Kenneth J. Alford, a pseudonym of British Bandmaster Frederick J. Ricketts. The Colonel Bogey strain was accompanied by a counter-melody using the same chord progressions, then continued with film composer Malcolm Arnold's own composition "The River Kwai March," played by the off-screen orchestra taking over from the whistlers, though Arnold's march was not heard in completion on the soundtrack. Mitch Miller had a hit with a recording of both marches. Besides serving as an example of British fortitude and dignity in the face of privation, the "Colonel Bogey March" suggested a specific symbol of defiance to British film-goers, as its melody was used for the song "Hitler Has Only Got One Ball." Lean wanted to introduce Nicholson and his soldiers into the camp singing this song, but Sam Spiegel thought it too vulgar, and so whistling was substituted. However, the lyrics were, and continue to be, so well known to the British public that they didn't need to be belaboured. The soundtrack of the film is largely diegetic; background music is not widely used. In many tense, dramatic scenes, only the sounds of nature are used. An example of this is when commandos Warden and Joyce hunt a fleeing Japanese soldier through the jungle, desperate to prevent him from alerting other troops. Arnold won an Academy Award for the film's score. Lean later used another Allford march, "The Voice of the Guns," in Lawrence of Arabia. Box office performance Variety reported that this film was the #1 moneymaker of 1958, with a US take of $18,000,000.[8] The second highest moneymaker of 1958 was Peyton Place at $12,000,000; in third place was Sayonara at $10,500,000.[8] Awards Academy Awards The Bridge on the River Kwai won seven Oscars: Best Picture — Sam Spiegel Best Director — David Lean Best Actor — Alec Guinness Best Writing, Screenplay Based on Material from Another Medium — Michael Wilson, Carl Foreman, Pierre Boulle Best Music, Scoring of a Dramatic or Comedy Film — Malcolm Arnold Best Film Editing — Peter Taylor Best Cinematography — Jack Hildyard It was nominated for Best Actor in a Supporting Role — Sessue Hayakawa BAFTA Awards Winner of 3 BAFTA Awards Best British Film — David Lean, Sam Spiegel Best Film from any Source — David Lean, Sam Spiegel Best British Actor — Alec Guinness Golden Globe Awards Winner of 3 Golden Globes Best Motion Picture — Drama — David Lean, Sam Spiegel Best Director — David Lean Golden Globe Award for Best Actor - Motion Picture Drama — Alec Guinness Recipient of one nomination Best Supporting Actor — Sessue Hayakawa Other awards New York Film Critics Circle Awards for Best Film Directors Guild of America Award for Outstanding Directorial Achievement in Motion Pictures (David Lean, Assistants: Gus Agosti & Ted Sturgis) New York Film Critics Circle Awards for Best Director (David Lean) New York Film Critics Circle Awards for Best Actor (Alec Guinness) Other nominations Grammy Award for Best Soundtrack Album, Dramatic Picture Score or Original Cast (Malcolm Arnold) Recognition The film has been selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry. British TV channel Channel 4 held a poll to find the 100 Greatest War Movies in 2005. The Bridge on the River Kwai came in at #10, behind Black Hawk Down and in front of The Dam Busters. The British Film Institute placed The Bridge on the River Kwai as the eleventh greatest British film. American Film Institute recognition 1998 — AFI's 100 Years... 100 Movies — #13 2001 — AFI's 100 Years... 100 Thrills — #58 2005 — AFI's 100 Years... 100 Movie Quotes o "Madness. Madness" — Nominated 2006 — AFI's 100 Years... 100 Cheers — #14 2007 — AFI's 100 Years... 100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition) — #36 First telecast The film was first telecast, uncut, by ABC-TV in color on the evening of September 25, 1966, as a three hours-plus special on The ABC Sunday Night Movie. The telecast of the film lasted more than three hours because of the commercial breaks. It was still highly unusual at that time for a television network to show such a long film in one evening; most films of that length were still generally split into two parts and shown over two evenings. But the unusual move paid off for ABC—the telecast drew huge ratings.[9] On the evenings of January 28 and 29, 1973, ABC telecast another David Lean color spectacular, Lawrence of Arabia, but that telecast was split into two parts over two evenings.[10] Restorations On November 2, 2010, Columbia Pictures released a newly restored The Bridge on the River Kwai for the first time on Blu-ray. According to Columbia Pictures, they followed an all-new 4K digital restoration from the original negative with newly restored 5.1 audio.[11] The Original Negative for the feature was scanned at 4k (roughly four times the amount of resolution in High Definition), and the color correction and digital restoration were also completed at 4k. The negative itself manifested many of the kinds of issues one would expect from a film of this vintage: torn frames, imbedded emulsion dirt, scratches through every reel, color fading. Unique to this film, in some ways, were other issues related to poorly made optical dissolves, the original camera lens and a malfunctioning camera. These problems resulted in a number of anomalies that were very difficult to correct, like a ghosting effect in many scenes that resembles color misregistration, and a tick-like effect with the image jumping or jerking side-to-side. These issues, running throughout the film, were addressed to a lesser extent on various previous DVD releases of the film and might not have been so obvious in standard definition.[12] See also BFI Top 100 British films List of historical drama films List of historical drama films of Asia To End All Wars (film) Return from the River Kwai (1989 film) References 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. ^ Commonwealth War Graves Commission: Kanchanaburi War Cemetery ^ links for research, Allied POWs under the Japanese ^ a b c Summer, Julie (2005). The Colonel of Tamarkan. Simon & Schuster Ltd. ISBN 0-7432-6350-2. ^ Brownlow, Kevin (1996). David Lean: A Biography. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-145780. pp. 391 and 766n ^ Davies, Peter N. (1991). The Man Behind the Bridge. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 0-485-11402-X. ^ (Piers Paul Read, Alec Guinness, 293) ^ The Colonel Bogey March MIDI file ^ a b Steinberg, Cobbett (1980). Film Facts. New York: Facts on File, Inc.. p. 23. ISBN 0-87196-313-2. When a film is released late in a calendar year (October to December), its income is reported in the following year's compendium, unless the film made a particularly fast impact. Figures are domestic earnings (United States and Canada) as reported each year in Variety (p. 17). ^ http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0050212/trivia ^ http://www.tvobscurities.com/2010/05/nielsen-top-ten-january-29th-february-4th-1973/ ^ http://bridgeontheriverkwaibd.com/ ^ http://www.sonypictures.com/homevideo/columbiaclassics/in-production/ ^ http://www.thegoonshow.net/facts.asp ^ "Wayne and Shuster Show, The Episode Guide (1954-1990) (series)". tvarchive.ca. http://www.tvarchive.ca/database/18984/wayne_and_shuster_show,_the/episode_guide/. Retrieved 200711-03.