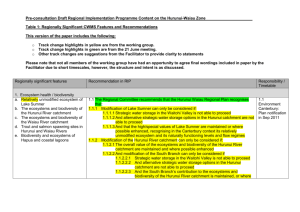

Fig 7. Changes to household demographics following the earthquakes

advertisement