Grant Writing: NSF, NIH, DOE Funding Guide

advertisement

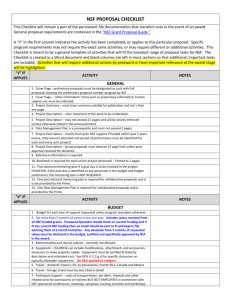

Introduction to grant writing Most U. S. science is ultimately funded by the U. S. taxpayer National Science Foundation – chemistry, physics, basic science National Institutes of Health – biology, biochemistry, medicine, anything with direct clinical relevance Department of Energy – chemistry, materials science, biology Department of Defense – chemistry, materials science This funding is obtained through a competitive grant-writing process. What do I know about proposals? Wrote two grant renewals during my postdoc, one of which got funded. Wrote 10 proposals at TCU. Two have been funded: a small TCU-only JFSRP, and a large collaboration with Texas A&M Qatar (http://www.qnrf.org/awarded/nprp/3/index.php?ELEMENT_ID=1223) Timeline: (1) Funding agency posts request for proposals. These are typically focused on a specific topic that a program manager wishes to fund. They are posted online at the agency website and/or http://www.grants.gov/ . Each request has a window for proposal submission, for example this catalysis program: http://www.nsf.gov/funding/pgm_summ.jsp?pims_id=13360 These requests come with a 50100 page document with details of writing process, proposal format, etc. The NSF Grant Proposal Guide is at http://www.nsf.gov/publications/pub_summ.jsp?ods_key=gpg . (2) Principle investigators (PIs) search through these lists of grant opportunities and find something that overlaps with their research (3) PI starts by contacting the program manager with a brief description of the proposed research project, to confirm whether it is consistent with the focus of the grant program (4) Many grants require a 2-4 page “preproposal” used for a preliminary sort. PIs with successful preproposals are requested to submit a 15-20 page full proposal. For example, the 2010 Department of Energy Early Career program requested 1,300 full proposals from an uncountable number of preproposals: http://www.er.doe.gov/sc-2/early_career.htm (5) PI writes and submits the grant proposal (6) Funding agency sends the full proposal out to reviewers in the field. (Once you start submitting proposals, you’ll get other peoples’ proposals to review.) (7) Based on the proposals and the reviewer reports, the funding agency decides (typically within 3-6 months) which proposals to fund. Ingredients of a proposal: Research proposals require a lot of things in addition to scientific content! The NSF’s “Grant Proposal Guide” linked above includes 40 pages of “Proposal Preparation Instructions”, from broad instructions on the project summary to details of font size and page margins. Funding agencies are typically very picky about these things, and good proposals can be turned down if, e.g., they have a special character in a section title! (Grants are a “buyer’s market”!) Criteria for proposal review: NSF focuses on “Intellectual merit” and “Broader impact”, as described in the following grant-ese: What is the intellectual merit of the proposed activity? How important is the proposed activity to advancing knowledge and understanding within its own field or across different fields? How well qualified is the proposer (individual or team) to conduct the project? (If appropriate, the reviewer will comment on the quality of prior work.) To what extent does the proposed activity suggest and explore creative, original, or potentially transformative concepts? How well conceived and organized is the proposed activity? Is there sufficient access to resources? What are the broader impacts of the proposed activity? How well does the activity advance discovery and understanding while promoting teaching, training, and learning? How well does the proposed activity broaden the participation of underrepresented groups (e.g., gender, ethnicity, disability, geographic, etc.)? To what extent will it enhance the infrastructure for research and education, such as facilities, instrumentation, networks, and partnerships? Will the results be disseminated broadly to enhance scientific and technological understanding? What may be the benefits of the proposed activity to society? Some other agencies focus exclusively on the scientific content, but this is becoming less common. Some keys to writing a proposal: Discuss the practical importance of the project. Pure research is great, but funding agencies and reviewers prefer projects that combine pure research with practical potential. Read all of the grant guidelines, and adhere closely to them. Reviewers have an incentive to discard your proposal for formatting problems, as it means they don’t have to read it carefully! Our discussions on “talking to nonspecialists about research” play a big role here. The NSF specifically requires that the first page of the proposal be accessible to nonspecialists. Always include preliminary results. Some PIs’ strategy is to write the proposal after doing the research! Then they use the grant to fund the next phase of the project.