Fagan, Rachel article 2015 - Friends of the Osborne Collection of

advertisement

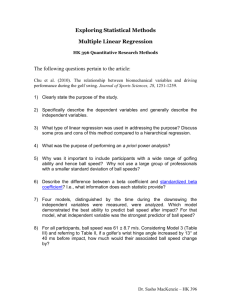

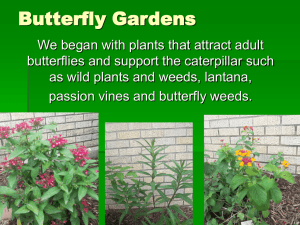

Georgian Era Party Crashing at the Butterfly’s Ball by Rachel Fagan The end of England’s eighteenth century brought a shift in genre and tone for children’s literature. Previously, eighteenth-century children’s books were primarily focused on the conveyance of moral and religious didacticism. By the late 1700s children’s literature was evolving towards entertaining prose and verse for children, a revival of fairy tales, poetry, and much more. Moral tales were still published but in tandem with this new literary model. This change was propelled by the enormous popularity of a handful of books published at the end of the long eighteenth century. Pivotal works include: The Comic Adventures of Old Mother Hubbard and Her Dog, 1805 by Sarah Martin and The Adventures of a Pincushion, 1780 – both available at the Osborne Collection. William Roscoe’s The Butterfly’s Ball, and the Grasshopper’s Feast soon followed. Initially published in a magazine; in 1807, The Butterfly’s Ball, and the Grasshopper’s Feast was printed in book form, accompanied by William Mulready’s copperplate engravings. The book was such a huge success that it inspired approximately a dozen other books - The Peacock at Home is held up as the best of the lot. Roscoe’s short book is set in verse and depicts the amalgamation of a group of children at play with an array of insect, a festive interaction between man and nature. The Butterfly’s Ball and the Grasshopper’s Feast illustrates human supremacy over the natural world and all its creatures. Roscoe supports this theme with child characters, a parallel to children’s new possession of a developing literary genre. The rhythmic verse set to pictures, fluidly guides the reader on a journey through the text as a voyeur of the festivities while maintaining a distance between self and other – children and insects. The book begins with an invitation from a child to his friends and readers: “Come, take up your Hats, and away let us haste/ To the Butterfly’s Ball and the Grasshopper’s Feast (Roscoe 1)1.” The text offers a voyeuristic journey to the butterfly’s ball. In the illustration, the children are inside a home, looking out the doorway to the natural world. The child gestures towards the doorway with a sweep of his hand, illustrating the children’s ownership of the natural world and seamlessly connecting the introduction to the rest of the text. On the following page the Trumpeter Gad-Fly has already begun summoning the other partygoers and a troop of gaudy insects emerge from the wood work: “And there came the Gnat, and the Dragon-Fly too/ And all their relations, Green, Orange, and Blue (Roscoe 10).” The rest of the text is set outdoors, in the realm of the insects. The children are never shown in the same space as the other partygoers, only as an isolated group, emphasizing their position as voyeurs rather than participants. To enforce the idea of one-sided dominance, the polarity of self and other is implicit throughout the poem by this division. This accentuates the children’s supremacy over nature by their aloof position, always separated from the insects by the physical space of the book. Instead of illustrating literal insects, as later versions of The Butterfly’s Ball and the Grasshopper’s Feast did, most of Mulready’s insects are people dressed as insects. The body and form of the insect is appropriated by the human form. The revelers are literally anthropomorphized into people. The few “real” insects are shown being ridden on by the humaninsects. In the above illustration, the trumpeter is standing on top of the gadfly, each foot firmly planted on its wings. This is a physical manifestation of the thematic implications of the children’s ascendency of nature. The earth and the natural world as a possession to be owned by the children in this book is most prevalent in the fourth couplet: See the Children of Earth, and the tenants of Air, For an Evening’s Amusement together repair (Roscoe 6). In these lines, the children are “of the earth” while the insects are “tenants.” This literally locates the children and insects on different social and hierarchical plains, inextricably correlating children to ownership and dominance. This delineation mirrors eighteenth-century class hierarchies and the division between the upper and lower classes – owners and renters, respectively. As one of the first British books written for children in verse as well as for their enjoyment, the sense of possession by the children in the text is paralleled to the children’s ownership in the book itself. The Butterfly’s Ball was initially written for Robert, one of Roscoe’s 10 children, on his birthday. The inscription on the cover reads, “Said to be written for the use of his children by Mr. Roscoe (Roscoe).” This book is the property of a child. After publication, The Butterfly’s Ball became the possession of an expansive audience of children. The size of the book itself is indicative of the audience; four inches by six inches - a small book for a small reader full of very small partygoers. Soon the butterfly’s ball is underway. A mushroom stands in for a table, covered in a leaf to serve as tablecloth, and quickly laden with a variety of meat. Though a sociable bee brings honey to add to the bounty his not so friendly relatives the hornet and the wasp arrive at the ball as well: “But they promised that Evening to lay by their sting (Roscoe 14).” The threat of these two companions is extinguished for the evening, but the mention of their sting is a reminder that it exists and will be rekindled after the festivities are over. This creates the necessity for a barrier between the children and the insects. Despite the merry festivities and oncoming feast elements of discord loom in the background, an ever present reminder to the characters and readers of the essential division between self and other. As the party draws to a close the division between self and other is written into the text with the use of words like us: So home let us hasten, while yet we can see. For no Watchman is waiting for you or for me. (Roscoe 29) The use of the words us, we, and “for you or for me” (Roscoe 29) distances the children from the insects by implying the insects are not part of this collective while including Roscoe’s reader . The insects are the other, excluded from the definitive umbrella of pronouns. The Butterfly’s Ball and the Grasshoppers Feast was such a beloved and cherished work that it was set to music at the behest of King George III and Queen Charlotte for their son. The new genre of children’s literature came to dominate the previous tradition of moral and religious didactic works. Prophetically, The Butterfly’s Ball, and the Grasshopper’s Feast gives the subject of dominance finality; insects are physically and analytically dominated by the human form. Finally, social hierarchies aside, the picture book eloquently and fluidly recreates the magical revels of the butterfly’s ball, beckoning the reader to join in: “And the Revels are now only waiting for you.” (Roscoe 6) Endnotes 1. This edition doesn’t have page numbers. For the purpose of this article, I’ll refer to the page numbers according to the title page as the second page and include the blank pages as numbered pages. The images are reproduced from the Holp Shuppan facsimile edition of The Butterfly’s Ball by Mr. Roscoe, London, John Harris, 1807, Osborne Collection of Early Children’s Books, Toronto Public Library. Works Cited Roscoe, William. The Butterfly’s Ball and the Grasshopper’s Feast. The Corner of St. Paul’s Church-yard: Juvenile Library, 1807. Print. Bibliography Carpenter, Humphrey and Mari Prichard. Oxford Companion to Children’s Literature. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1984. Print. Thwaite, Mary F. From Primer to Pleasure in Reading. Boston: The Horn Book, 1972. Print. Rachel Fagan is currently a student at the University of Toronto