THE LEGISLATIVE PROCESS 1

advertisement

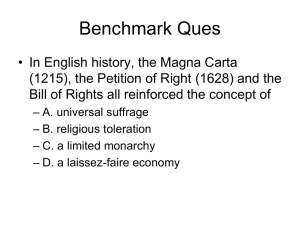

THE LEGISLATIVE PROCESS Statutes are made by Parliament which consists of the House of Commons, the House of Lords and the Monarch. Another term for a statute is an Act of Parliament. In Britain, Parliament is sovereign which has traditionally meant that it can make or cancel practically any law that it wants and any law that it does make takes precedence over law originating from another source (e.g. common law). However, the UK’s membership of the EU has eroded this principle somewhat by stating that some EU laws are to take precedence regardless of member state legislation i.e. where a statute is in contravention of an applicable EU law then the courts should follow the EU decision. As an ‘arm of the state’, Parliament is referred to as the Legislature in that it makes legislation All current UK legislation can be found at: http://www.legislation.gov.uk A useful website for an explanation of the British Political System can be found at: http://www.rogerdarlington.me.uk/Britishpoliticalsystem.html#Legislation The House of Commons This is the democratically elected part of Parliament where every 4-5 years, Members of Parliament (MPs) are elected by the public in general elections. There must be an election every 5 years although one can be called sooner by the Prime Minister. There are approximately 650 MPs whose job it is to look after their constituencies (areas of the country) by discussing the relevant political issues and proposals for new law. The Government is the party of MPs who win the most ‘seats’ at an election and are asked by the monarch to govern the day to day running of the country. At the moment we have a coalition government between the Conservatives and the Liberal Democrats. 1 House of Lords Despite no longer being a part of the judiciary, the House of Lords is still a part of the legislature although it has limited power in terms of actually making or blocking legislation. This is primarily because the members of the House of Lords are not democratically elected by the public. Its main role is to revise legislation and keep a check on Government by scrutinising its activities. Ultimately however, it cannot block the legislative will of Government. The majority of the members of the House of Lords are appointed by the Queen on recommendation of the House of Lords Appointments Commission. There are currently about 750 members made up of: Life Peers Retired judges of the former House of Lords judicial committee Bishops (only a small number) Elected hereditary peers Historically most members of the House of Lords have been what we called hereditary peers. This meant that years ago a king or queen nominated a member of the aristocracy to be a member of the House and, since then, the right to sit in the House has passed through the family from generation to generation. Clearly this is totally undemocratic and the last Labour Government abolished the right of all but 92 of these hereditary peers to sit in the House. Almost all the other members of today's House of Lords are life peers. This means that they have been chosen by the Queen, on the advice of the Government, to sit in the House for as long as they live, but afterwards no member of their family has the right to sit in the House. Many are former senior politicians. Others are very distinguished figures in fields such as education, health and social policy. There are unfinished proposals for House of Lords reform which are based on the idea that the whole of the House should be elected with no hereditary peers; this has received cross party approval. Incidentally, the only other unelected second chamber in the world is found in Lesotho, a small country completely surrounded by South Africa. 2 MAKING AN ACT OF PARLIAMENT Most acts of Parliament evolve from the Government’s manifesto that is published in the run up to the election. The manifesto is a series of ‘promises’ that the Government makes in relation to how they are going to govern the country should they come to power. The other main way in which a policy objective may come to light is through its inclusion in an official consultation document known as a ‘Green Paper’. The Green Paper puts forward possible suggested proposals for law or reform of law, which interested parties may consider and give their view on. This may then be followed by a White Paper which contains specific plans for reform. If these consultation papers gain interest then they may move on to become bills. BILLS All statutes begin as a Bill, which is a proposal for a specific piece of legislation which has been formally drafted. A Bill will only become an Act of Parliament is it successfully completes all the necessary stages in Parliament. The actual preparation of a Bill is done by expert draftsmen known as Parliamentary Counsel. There are three main types of bill: 1. Public Bills: Presented to Parliament by Government ministers with the intention of changing the general law affecting the whole of the country or a large proportion of it. 2. Private Members’ Bills: Prepared by an individual backbench MP (someone who is not a part of the Cabinet/Shadow Cabinet) who has an interest in a particular issue. In order to put forward a Private Members’ Bill, the MP must enter a ballot to win the right to do so. If they win they will have to persuade Parliament to give enough time to the Bill to allow it to go through. Consequently, not very many Bills succeed in becoming law through this process, however some important contributions have been made to legislation in this way e.g. Abortion Act 1967 which legalised abortion in this country and the Marriage Act 1994 which allowed people to marry in registered places not only churches and Register Offices 3. Private Bills: These are Bills prepared usually by local authorities, public corporations or large public companies and usually only affect the sponsor, not the law for the general population as a whole. For example a local authority might seek authority to build a new road. 3 PARLIAMENTARY PROCESS Once a Bill has been proposed, it then has to go through a series of steps in both the House of Commons and the House of Lords in order for it to become an Act of Parliament/Statute. 1. FIRST READING: The name and the main aims of the Bill are read out in the House of Commons and usually no discussion takes place but there will be a vote on whether the House wishes to consider the Bill further; if so, it will continue to the next stage, but if not, it will end here. 2. SECOND READING: The proposals are debated fully and may be amended and members again vote on whether the legislation should proceed. The system of party ‘whips’ (whose job it is to make sure that MPs vote in line with their party) means that usually a Government with a reasonable majority can almost always get its legislation through this stage 3. COMMITTEE STAGE: The Bill is referred to a committee of the House of Commons for detailed examination of each clause of the Bill. The Committee will consist of between 16-50 MPs which will be chosen specifically in relation to the qualifications or interests that the MPs have with regard to the matter being debated. This is known as a ‘Standing Committee’. The Committee will not only include MPs from the Government but also opposition MPs. 4. REPORT STAGE: This is where the Committee reports back to the House on proposed amendments that they have made to the Bill during the debate. Any proposed amendments will be further debated in the House and be voted on to see whether they are included in the Bill. 5. THIRD READING: The Bill is again presented to the House and there may be a short debate before the final vote. This is somewhat of a formality as any Bill that has got this far is unlikely to fail at this stage. 6. HOUSE OF LORDS: The Bill then goes to the House of Lords where it goes through a similar process of three readings. If the House of Lords alters anything, the Bill returns to the Commons for further consideration. The Commons then responds with agreement, disagreement or proposals for alternative changes. 7. ROYAL ASSENT: In the vast majority of cases, agreement between the Commons and Lords is reached and the Bill is presented for Royal Assent. The Queen must give her assent to the Bill before it can become law but in practice this assent is never refused. 4 The Bill is then an Act of Parliament and becomes law though most do not take effect immediately upon the Queen giving her assent, but on a specified date in the near future or by an MP issuing a Commencement Order. This delayed commencement can cause confusion in certain circumstances; the Criminal Justice Act 2003 is a good example of this as it was brought in bit by bit: 339 sections and approximately 30 schedules with the commencement details in section 336 11 sections (mostly administrative) came into effect immediately upon Royal Assent Ss 269-277 came into effect 4 weeks after Royal Assent The commencement section said that the other sections would come into effect when the relevant minister issued a commencement order so some came into force in January, February, April and June 2004 with some sections still not being in force. Some Acts never come into force. The Easter Act 1928 was designed to fix the date of Easter Day but despite going through all the necessary stages in Parliament, it has never been brought into force. 5 HOUSE OF LORDS’ POWERS TO BLOCK LEGISLATION It is worth noting that at one time legislation could not be passed unless both the House of Commons and the House of Lords agreed on the Bill which meant that the unelected House of Lords could block legislation put forward by the elected House of Commons. The Parliament Acts of 1911 and 1949 give special procedures for when a Bill can go for Royal Assent without the approval of the House of Lords after a specified period of time. These procedures are rarely used (mainly because the House of Lords usually drops their objections) but the use of the Parliament Acts to force legislation has increased in recent years, most notably with the Hunting Act 2004 which banned fox hunting and was unpopular in the House of Lords The Parliament Acts can be used when it is a matter of general law but not when the Bill is proposing making a major constitutional change. 6 CRITICISMS OF THE LEGISLATIVE PROCESS There is a significant amount of criticism in relation to the legislative process of the UK and this has been going on for centuries. The Renton Committee on the Preparation of Legislation produced a report in 1975 and in that they actually used a 400 year old quote from King Edward VI saying: I would wish that the superfluous and tedious statutes were brought into one sum together, and made more plain and short, to the intent that men might better understand them. The Renton Commission highlighted 4 main complaints with the legislative process: 1. The language used in many Acts was obscure, old fashioned and complex 2. Acts were over-elaborate because draftsmen tried to cover every eventuality that the Act might have to deal with 3. The structure of many Acts was illogical with lots of sections appearing to be out of sequence making it difficult for people to find relevant sections 4. There was a lack of clear connection between Acts so it was not easy to trace all the Acts relating to one topic Location: Ideally, as all citizens have to abide by all laws, then they should be easily accessible by everyone but this is certainly not the case. As well as finding the relevant Act, it is also difficult to know which sections are in force etc Amendments: Many statutes are amended by later statutes so that it can be necessary to read two or more Acts together to get the full provisions. It may also be added to by delegated legislation (legislation made by local authorities or Government departments etc) and so there are other sources to consider Language: Not always easily understood and approximately 75% of cases heard by Supreme Court (House of Lords) in its appeal capacity relate to the interpretation of the words of Acts. Ideas for reform from the 1992 Hansard Society Commission were based on the idea of democratic law making which suggested that: Laws are made for the benefit of the citizens and all citizens should therefore be involved as fully and openly as possible in the legislative process Statute law has to be rooted in the authority of Parliament and thoroughly exposed to democratic scrutiny 7 Statute law should be as certain and intelligible as possible Statute law has to be accessible as possible Getting the law right is as important than getting it passed quickly PARLIAMENTARY SOVEREIGNTY The idea of Parliamentary Sovereignty means that the law made by Parliament overrides any other form of law in England and Wales i.e. custom, judicial precedent (common law), delegated legislation or previous Acts of Parliament. You might also see this referred to as Parliamentary Supremacy. The concept is rooted in the idea of democratic law making in that the MPs making the laws are elected by, and therefore working for, the public so that effectively they are participating in the legislative process on behalf of the voter. This however, is a very idealistic view which has several problems: MPs usually vote how their party wants them to vote MPs are often elected on very small majorities meaning that a large proportion of their constituency may not agree with their policies General elections only happen every 4-5 years meaning that an MP who votes in a way that is not popular with the public is not immediately replaced Albert Dicey, who was a legal commentator on the Rule of Law in the nineteenth century, made 3 main points about the idea of Parliamentary Sovereignty: 1. Parliament can legislate on any subject matter 2. No Parliament can be bound by any previous Parliament, nor can a Parliament pass any Act that will bind a later Parliament 3. No other body has the right to override or set aside an Act of Parliament. You must research these 3 points and provide your opinions on whether you think they are accurate or not. 1. ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 8 2. ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 3. ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… LIMITATIONS ON PARLIAMENTARY SOVEREIGNTY The two main limits on Parliamentary Sovereignty are fairly modern limitations and relate to: 1. Membership of the European Union 2. Effect of the Human Rights Act 1998 Membership of EU UK joined the EU in 1973 and in order to become a member, Parliament passed the European Communities Act 1972 which effectively means that membership of the EU means that EU laws take priority over English law even when English law was passed after the relevant EU law. Example is the Merchant Shipping Act 1988 which stemmed from Spanish fishing fleets registering boats in the UK in order to take advantage of UK fishing quotas rather than reducing the Spanish quotas. The Act stated that 75% of the shareholders of the fishing boat should live in the UK for it to be registered there. The ECJ said that this Act was contrary to EU law under which citizens of all member states can work in other member states meaning that Merchant Shipping Act 1988 was not effective against other EU citizens. 9 Human Rights Act 1998 This states that all Acts of Parliament have to be compatible with the European Convention on Human Rights. It is possible to challenge an Act on the grounds that it does not comply with the Convention and under s4 Human Rights Act 1998 the courts have the power to declare an Act incompatible with the Convention. Following a declaration of incompatibility it is common for the Government to either repeal or amend the law or even introduce a whole new law to make the situation compatible. However, it must be remembered that it is not necessary for the Government to do this but it would be politically unpopular if they did not. 10