My Analysis Essay

advertisement

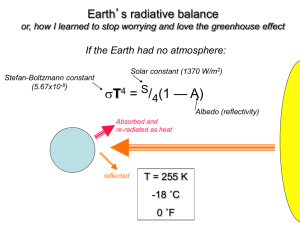

Kastner 1 Stacy Kastner Dr. Stacy Kastner ENG 1103 1 October 2013 The Right to Life, Liberty, the Pursuit of Happiness…and Light Bulbs? In her article “Global Warming Statists Threaten Our Liberty,” Daneen Borelli opens with a dramatic patriotic appeal, citing the opening of the Declaration of Independence—“Life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” (197)—in order to evoke in readers a sense of patriotic resistance against energy efficiency regulations of products like automobiles and light bulbs. Borelli graduated from Pace University with a B.A. in Managerial Marketing, is a Tea Party member, frequent speaker and writer affiliated with conservative news outlets, and an advocate for “freedom and limited government” (“About Daneen”). It is likely that The National Center for Public Policy Research—a conservative “research foundation” (“About Us”)—called upon Borelli to write this article due to her reputation as an advocate for hands-off government. In “Global Warming Statists,” Borelli argues that “left-wing activists” (197) and “their allies in government” (198) are proposing tightened energy efficiency regulations at the expense of Americans’ civil liberties. She claims that such calls for increased regulations are not supported by statistical data, stating in her third paragraph: “What is unresolved is the role man actually plays in climate change” (198). Ultimately, Borelli argues that since it unclear whether or not human actions contribute to global warming, it is a violation of human rights to limit consumer choices based on global warming concerns. Borelli points to three specific instances of activist and governmental calls for tightened regulations, arguing that each instance threatens “the freedom of consumer choice” (198). The Kastner 2 first example that she points to is a recent energy bill that raised the standard miles per gallon for automobiles; the second example that she points to is support from activists and politicians to make “energy efficient compact florescent light bulbs (CFLs)” (198) the only light bulbs available for purchase; and the third example that she points to is PETA’s using the greenhouse gases produced in raising farm animals as an argument to promote veganism. Though Borelli crafts a provocative argument—appealing to one’s sense of constitutionally granted rights is certainly going to garner attention—her argument is ineffective because of a lack of sufficient evidence and unsupported generalizations. Though she offers concrete examples of activist and politicians’ calls for and governmental regulations of consumer products in response to concerns for global warming, she does not offer any evidence supporting her claim that human involvement in global warming is inconclusive, and, likewise, she jumps to unsupported conclusions about the relationships between gas mileage and vehicle size and light bulbs and mercury contamination; such faulty rhetoric does not just weaken but entirely invalidates her argument. The cornerstone of Borelli’s argument rests on her claim that there is no indisputable evidence linking human product consumption to global warming. Though Borelli claims that one cannot know if humans impact global warming, nowhere in her article does she provide evidence in support of this claim. For example, in her second paragraph she writes: “It is easy to be skeptical of the man-made global warming hysterics when the scientific data remain inconclusive” (198). She suggests that those who discuss human beings’ contributions to global warming are “hysterics”; yet, she does not cite any examples confirming this hysteria, nor does she provide readers with scientific rebuttals to research arguing that global warming is manmade. Though she refers to scientific “ambiguity” and calls research supporting human beings’ Kastner 3 negative impact on the environment a “dubious theory” (198) she has not actually proved that this ambiguity exists. Had Borelli cited evidence from scientific studies indicating that human beings’ negative impact on the environment is, indeed, questionable, or, were Borelli herself an expert on global climate change, readers might be able to accept her claims; however, without evidence and expertise, her claims lack the evidence necessary to give them any persuasive force. Borelli’s argument is also built upon examples of how energy efficiency regulations are negatively impacting consumer choices. As she explains in her fifth paragraph, “Cars and trucks are at the top of the leftist hit list” (198). However, while Borelli does provide an example of how energy efficiency regulations are impacting a specific consumer product, she does not provide an example that such regulations are actually negatively impacting consumer choices. Yes, regulations, as Borelli points out, have increased the “average fuel economy” of vehicles (198), but this does not simultaneously mean, as Borelli suggests, that “vehicles will inevitably become smaller and lighter” (198). In order to make this connection, Borelli would need to provide evidence that there is has been an established cause-and-effect relationship, and she does not. Instead, she further falls into unsupported generalizations about the impact of new minimum miles per gallon regulations, writing, “Consumers who need or prefer bigger and safer vehicles will have fewer choices.” Failing to provide evidence for such claims, Borelli offers readers unsupported generalizations, which, again, serve to weaken her argument rather than support it. Just as she needs scientific evidence and expertise to support claims about the ambiguity of data supporting human beings’ contributions to global warming, she needs data showing a correlation between increased fuel efficiency regulations and changes in the size and safeness of vehicles being produced in order for claims to be convincing. Kastner 4 As one final example of how Borelli’s use of unsupported generalizations invalidate her argument, in her sixth paragraph she turns her attention to calls to make a permanent move from incandescent light bulbs to CFLs. Though, again, she provides an example of the impact of energy efficiency regulations in consumer choices, she does not provide evidence to support her claim about the negative impact of such changes. For example, Borelli argues that though CFLs “are said to last longer and reduce power-plant emissions of carbon dioxide, they have a number of drawbacks” (198). Though Borelli claims that there are “a number of drawbacks,” she cites only one—that CFLs contain mercury—and her explanation of the possible dangers due to this are speculated. For instance, she uses the language “which mean they may”—invoking the exact ambiguity that she criticizes in her opposition’s arguments. Though Borelli writes that those who are critical of human beings’ contributions to global warming “want a discussion based on logic and facts” (198), she, one of these critics, studiously avoids both logic and facts in her own discussion, “Global Warming Statists Threaten Our Liberty.” Had Borelli taken her own advice and provided support for her claims about the ambiguity concerning scientific studies of human impact on global warming, evidence linking gas mileage regulations to decreased consumer choices, and evidence confirming the multiple and serious risks of CFLs, her argument may have been persuasive. However, due to a lack of evidence and unsupported generalizations, her argument was undermined by faulty logic and ultimately unsuccessful. Kastner 5 Works Cited “About Daneen.” Daneen Borelli: Igniting Liberty. Daneen Borelli, n.d. Web. 1 Oct. 2013. “About Us.” The National Center for Public Policy Research. The National Center, n.d. Web. 1 Oct. 2013. Borelli, Daneen. “Global Warming Statists Threaten Our Liberty.” Rpt. in The Little, Brown Handbook. 4th Custom ed. Eds. H. Ramsey Fowler and Jane E. Aaron. Boston: Pearson Learning Solutions, 2012. 197-8. Print.