Spotlight

advertisement

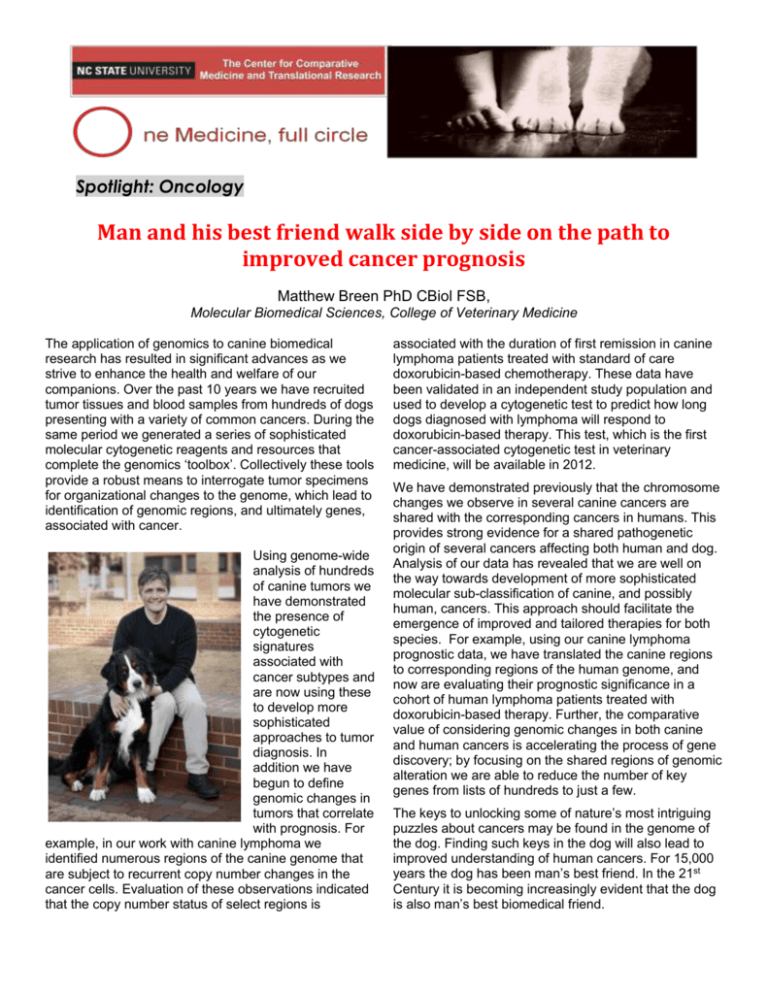

Spotlight: Oncology Man and his best friend walk side by side on the path to improved cancer prognosis Matthew Breen PhD CBiol FSB, Molecular Biomedical Sciences, College of Veterinary Medicine The application of genomics to canine biomedical research has resulted in significant advances as we strive to enhance the health and welfare of our companions. Over the past 10 years we have recruited tumor tissues and blood samples from hundreds of dogs presenting with a variety of common cancers. During the same period we generated a series of sophisticated molecular cytogenetic reagents and resources that complete the genomics ‘toolbox’. Collectively these tools provide a robust means to interrogate tumor specimens for organizational changes to the genome, which lead to identification of genomic regions, and ultimately genes, associated with cancer. Using genome-wide analysis of hundreds of canine tumors we have demonstrated the presence of cytogenetic signatures associated with cancer subtypes and are now using these to develop more sophisticated approaches to tumor diagnosis. In addition we have begun to define genomic changes in tumors that correlate with prognosis. For example, in our work with canine lymphoma we identified numerous regions of the canine genome that are subject to recurrent copy number changes in the cancer cells. Evaluation of these observations indicated that the copy number status of select regions is associated with the duration of first remission in canine lymphoma patients treated with standard of care doxorubicin-based chemotherapy. These data have been validated in an independent study population and used to develop a cytogenetic test to predict how long dogs diagnosed with lymphoma will respond to doxorubicin-based therapy. This test, which is the first cancer-associated cytogenetic test in veterinary medicine, will be available in 2012. We have demonstrated previously that the chromosome changes we observe in several canine cancers are shared with the corresponding cancers in humans. This provides strong evidence for a shared pathogenetic origin of several cancers affecting both human and dog. Analysis of our data has revealed that we are well on the way towards development of more sophisticated molecular sub-classification of canine, and possibly human, cancers. This approach should facilitate the emergence of improved and tailored therapies for both species. For example, using our canine lymphoma prognostic data, we have translated the canine regions to corresponding regions of the human genome, and now are evaluating their prognostic significance in a cohort of human lymphoma patients treated with doxorubicin-based therapy. Further, the comparative value of considering genomic changes in both canine and human cancers is accelerating the process of gene discovery; by focusing on the shared regions of genomic alteration we are able to reduce the number of key genes from lists of hundreds to just a few. The keys to unlocking some of nature’s most intriguing puzzles about cancers may be found in the genome of the dog. Finding such keys in the dog will also lead to improved understanding of human cancers. For 15,000 years the dog has been man’s best friend. In the 21st Century it is becoming increasingly evident that the dog is also man’s best biomedical friend.