Fol.Natalie_ Summary Case study

advertisement

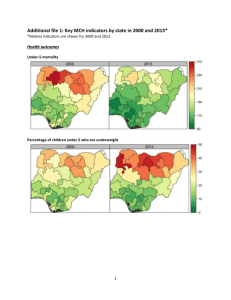

Natalie Fol – Case Study – July 2010 Resistance to polio vaccination: What can we learn from the “Social Norms” perspective? A case study based on the 2003/2004 northern Nigeria’s boycott Summary Vaccination is recognized by the international community as one of the key means to improve health. In 1988, the Global Polio Eradication Initiative1 (GPEI) was created to eradicate poliovirus. Between 1988 and 2003, major results have been achieved in the fight against the virus. In mid-October 2003, the GPEI launched what was hoped to be the final onslaught against polio. Unfortunately, three states in northern Nigeria decided not to participate due to doubts on vaccine safety. The boycott organized in northern Nigeria demonstrated that a change in assumptions on which a norm is based impact on individual expectations within a group. Rejecting the scientific-based acceptance of immunization, the religious and political leaders in northern Nigeria created another social norm against polio immunization based on political, cultural and religious values. As a result, normative and empirical expectations as well as sanctions attached to social norms relating to polio vaccination reversed and the behaviour based on non compliance with polio vaccination became the norm of the people living in the northern states involved. The boycott did not happen in a vacuum but can be linked to other public controversies around polio vaccination that emerged in the 1990s in numerous countries2. In Nigeria, it happened in a context of perceived cultural/political division between central and decentralized levels and was first and foremost motivated by an attempt by the local and traditional leaders to protect what they consider as “their” people from perceived risks. The perception of risks was based on various factors. It was first embedded in negative past reference related to immunization. In 1996, a western pharmaceutical conducted a trial in northern Nigeria to test the efficacy of its new antibiotic during an outbreak of meningitis. Lawsuit was undertaken against the company, alleging that the drug trial was illegal and that it had killed children included in the trial. In northern Nigeria and especially in Kano this event was still on people’s minds and had contributed to shape a negative bias against western pharmaceutical companies and immunization campaigns. Another important factor to consider is the perceived dissonance between two reference systems. The events around September 11 attack and the wars in the Middle East contributed to create a gap of fear and mistrust between the western world and the Muslim communities. Based on a religious rationale, if the Western world was engaged in wars against Iraq or Afghanistan, it led to the conclusion that it was a war 1 Public health initiative led by WHO, Rotary International, the US Centre for Disease, Control and Prevention (CDC) and UNICEF 2 Combatting Antivaccination Rumours: Lessons Learned From Case Studies In East Africa - UNICEF 2002 Natalie Fol – Case Study – July 2010 against all Muslims. The amalgam between politics and religious values shifted the debate around immunization from the scientific field to a moral field. The definition of the disease itself also led to a clash of perspectives, communities being inclined to recognize the one provided by their traditional system (traditional healers) and to reject the one provided by outsiders (western world / Scientific). Other factors, such as an inadequate provision and delivery of health services as well as a weak knowledge of parents in the field of immunization contributed to increase the confusion and to amplify a perception of fear and mistrust toward external systems. The diffusion of rumors and resistance seems to be linked to the Hausa identity, the dominant ethnic group in northern Nigeria, combined with strong Islamic religious values. The network analysis shows that various powerful channels were involved in the spread of the rumors, including religious and local leaders who benefit from a considerable level of credibility among the Hausa people. They are considered as the “gate keepers” of the Hausa tradition as well as of the religious values. The diffusion of the resistance was based on critical factors that allowed it to succeed. It includes; community discussion at various levels (households, through local media, communities); involvement of trusted local leaders; Strengthening of group identity, values and beliefs against external threats; Public statements of influential leaders largely amplified by Hausa and international media; Resistance perceived as a moral norm and a religious imperative hence providing a positive incentive to comply with the new norm. The response to rumors was organized on the same networks as the one used to create the widespread resistance. Partnerships with the most influential traditional leaders and community dialogue were the two main strategies used to overcome resistance. This led to a public declaration of the leaders of the resistance and allow to shift back to the initial script on which normative expectations related to polio vaccination was based prior to the boycott (I believe that others expect me to comply with immunization.”). To reinforce the power of their new positioning, they concretely translated their pledge into action and had their own children publically immunized. A lot has been achieved since 2004 resulting in a huge decrease in number of polio cases registered in Nigeria. However pockets of resistance remain and require us to review the situation. How can we better address resistance to polio vaccination through the lens of social norms? Various options including increase of community participation, reinforcement of the awareness of human rights principles at community level, improve common knowledge on polio and immunization issues, reinforcement of routine immunization as well as of primary health care system should be further explored and strengthened.