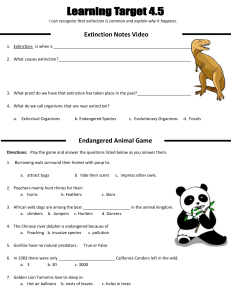

Extinction

advertisement

1 Extinction Overview Extinction is a procedure used in applied behavior analysis (ABA) in which reinforcement of a previously rewarded behavior is halted (Cooper, Heron, & Heward, 1987). Remember that reinforcement is a consequence delivered immediately after a behavior which increases the likelihood that the behavior will occur in the future. Examples of reinforcers typically include: o o o privileges to desired items and activities; social praise; and tokens. Reinforcement can be a powerful method for instruction and encouraging positive behaviors, such as teaching a child to speak or helping a student complete a task. However, sometimes reinforcement can inadvertently cause the occurrence interfering behaviors (e.g., disruptive, self-injurious, and/or repetitive/stereotyped behaviors). For example, if a teacher provides a verbal or emotional reaction following a student's inappropriate comments (and the student finds this reaction reinforcing), then this social attention may increase or maintain the student's inappropriate behavior over time. Procedures, such as extinction, sometimes need to be implemented to reduce these interfering behaviors. Extinction does not require the use of punishment procedures to decrease problem behavior. Extinction simply requires the withholding of reinforcement by ignoring a behavior denying access to tangible items or activities not allowing the learner to escape or avoid a non-preferred task or situation, and/or preventing reinforcing sensory feedback. For example, a teacher might ignore a student's inappropriate comments, so the student learns that his inappropriate comments no longer elicit a verbal or emotional reaction from the teacher - behaviors that the student finds reinforcing. [Keep in mind that some students actually find it reinforcing to see a teacher get upset.] 2 Applying extinction can occasionally lead to an increase in the frequency (i.e., how often the behavior occurs), duration (i.e., how long the behavior lasts) and/or intensity (i.e., how intense or powerful the behavior is) of the target behavior, referred to as an extinction burst. For instance, if a student's inappropriate comments are suddenly ignored by the teacher, the student may initially increase her rate or volume of inappropriate comments. The student's increase in behaviors can be thought of as "trying harder" to get the teacher's attention. If the teacher's attention (reinforcement) is consistently withheld, then the student's inappropriate comments will eventually decrease. Additional intervention strategies, such as functional communication training (FCT), differential reinforcement, non-contingent reinforcement, self-management, or response interruption/redirection (RIR) may be used to prevent or minimize the occurrence of an extinction burst and to teach the learner more appropriate, functional behaviors to replace the problem behavior. Please refer to AIM Modules on FCT, reinforcement, selfmanagement, and RIR to learn more about how to implement them in classrooms and programs. Extinction has been shown to be effective in a wide variety of settings, such as homes, schools, communities, and with diverse behaviors ranging from self-injury to mild behaviors (e.g., Hagopian, Fisher, Sullivan, Acquisto, & LeBlanc, 1998; Hall, Grinstead, Collier, & Hall, 1980; Harris, Wolf, & Baer, 1966; Lalli, Casey, & Kates, 1995; Rekers & Lovaas, 1974). In addition, extinction has been shown to produce substantial and rapid reductions in target behaviors (Higbee, Carr, & Patel, 2002; Rescorla & Skucy, 1969; Ringdahl, Vollmer, Borrero, & Connell, 2001; Thompson, Iwata, Hanley, Dozier, & Samaha, 2003; Uhl & Garcia, 1969). Pre-Assessment Pre-Assessment Extinction can be used to reduce or eliminate unwanted behavior. Select an answer for question 500 When extinction is used on a target behavior, initially the behavior is likely to: Select an answer for question 502 3 What is the term used to describe an increase in the target behavior's frequency and intensity as a result of removing the positive reinforcer? Select an answer for question 503 Extinction is often used with what other behavioral procedure to increase appropriate behavior? Select an answer for question 504 The evidence does not support the use of extinction procedures for children and youth with ASD. Select an answer for question 505 Which of the following target behaviors or skills are recommended for use with extinction? Select an answer for question 506 When might one want to use extinction procedures? Select an answer for question 507 True or False. Extinction procedures can be used by any professional introduced to the learner? Select an answer for question 508 What is Extinction? When using interventions that reduce interfering behaviors, the goal is to communicate one central message to the learner-The behavior is no longer effective and/or efficient at achieving its purpose and other, more appropriate behaviors, can achieve your goals. How this message is communicated to the learner may vary depending on the function of the learner's behavior, the beliefs and priorities of the parents, and the specific contexts in which the problem behavior occurs. One central strategy is extinction - that 4 is, withholding or minimizing, to the greatest extent possible, the delivery of the consequence that maintains the interfering behavior. Extinction can be used with behaviors previously maintained by positive or negative reinforcement and by naturally occurring sensory consequences. Each of these procedures is discussed further in the following section. Extinction is derived from applied behavior analysis (ABA) and involves procedures aimed at withdrawing or terminating the reinforcement associated with an inappropriate behavior. Because there may be a learning history in which the unwanted behavior has been reinforced over a period of time, changing the consequence to no longer reinforce the behavior may lead to an increase in the frequency and intensity of the behavior. Thus, it is important to be mindful of the possible extinction burst that may result from no longer reinforcing previous behaviors. However, extinction has been used with other intervention strategies to successfully teach children and adults with ASD a multitude of functional, meaningful behaviors and responses that discourage the use of inappropriate behaviors. Goals of Extinction Extinction procedures are combined with reinforcement procedures so that learners with ASD develop more appropriate skills in place of challenging or problematic behaviors that prevent the occurrence of more acceptable, purposeful behaviors. They can be used with other intervention strategies, including functional communication training, differential reinforcement, non-contingent reinforcement, and/or response interruption/redirection. Examples of specific skills that were the focus of extinction interventions in the evidence-based studies include: o functional communication (Kelley, Lerman, & Van Camp, 2002); o self-injurious behaviors (Kahng, Iwata, & Lewin, 2002; Matson & Santino, 2008); sleep problems (Weiskop, Matthews, & Richdale, 2001); and eliminating challenging behavior during classroom instruction (O'Reilly et al., 2007). o o Who Can Use Extinction? Extinction procedures can be developed and used with children with ASD by a variety of adults who have been appropriately trained, including parents, teachers, special 5 educators, therapists, and paraprofessionals. However, it is critical that the adult be familiar with the learner so that a plan for addressing an extinction burst is created should the unwanted behavior increase in intensity or frequency. Who Would Benefit Most from Extinction? Learners who have ASD who exhibit behaviors that interfere with learning and achievement can benefit from extinction. The use of extinction is not limited to a particular behavior or skill, but typically is used to address disruptive, aggressive, perseverative and stereotypical behaviors, or any other problematic behavior that prevents developmental growth. It is recommended that extinction procedures be used after other more positive interventions have been tried and shown to not work (e.g., differential reinforcement, curriculum modification, etc.). This is mainly due to the extinction burst that might occur as the learner seeks to receive reinforcers previously provided following the occurrence of the unwanted behavior. Step-by-Step Instructions for Implementation Extinction procedures can be implemented to decrease or eliminate problematic behaviors that interfere with or limit teaching opportunities. Typical extinction procedures include: o ignoring the behavior; o removing reinforcing items or activities; and/or removing the learner from the environment. o An extinction trial is each time the target behavior occurs and one of these procedures is used. The steps for implementing an extinction program include: o o o o identifying the unwanted behavior; identifying data collection methods and gathering baseline data; determining the purpose of the unwanted behavior; creating an intervention plan; 6 o o o implementing the intervention; collecting resulting data; and reviewing the intervention plan. The Step-By-Step Instructions that follow provide an in-depth description of each step needed to implement an extinction program effectively. Step 1. Identifying the Interfering Behavior When starting an extinction program, the first step is to identify the behavior that is interfering with a learner's development. Interfering behaviors might include disruptive, self-injurious, and/or repetitive/stereotypical behaviors. To identify a behavior, teachers and other practitioners (speech-language pathologists, behavioral specialists, paraprofessionals, and other team members) gather information from numerous individuals regarding the behavior's frequency, intensity, location, and duration, as well as what it looks like. Teachers/practitioners define the interfering behavior by focusing on: o o o o o what the behavior looks like (topography); how often the behavior occurs (frequency); how intense the behavior is (intensity); where the behavior occurs (location); and how long the behavior lasts (duration). The target behavior must be clearly defined so that teachers/practitioners can easily observe and measure the difference between when the behavior does and does not occur. A clearly defined target behavior also helps learners make the behavior easily recognizable. An observable and measurable description of the behavior should include what the behavior looks like (e.g., the body parts, movements, materials involved) and the setting(s) in which it occurs/is expected to occur. The description must be clear enough so that all team members who work with the learner with ASD in the intervention setting agree on when the behavior occurs and when it does not. 7 Step 2. Identifying Data Collection Measures and Collecting Baseline Data Teachers/practitioners identify how they will collect data used to measure the interfering behavior before starting the intervention. When collecting data for extinction, it is important to focus on the frequency, duration, and intensity of the behavior. Data collection sheets which measure these characteristics will be most appropriate for use with extinction. Teachers/practitioners gather baseline data on the interfering behavior. The data collection measures determined above would be used, along with the information gathered in Step 1, to determine the nature of the interfering behavior prior to the intervention. During the baseline phase, it is important to collect data for a long enough period of time to determine if there are any patterns. Teachers and/or other practitioners should decide how long data will be collected (e.g., one week, two weeks), and what will happen if there are not enough data to be considered useful (e.g., redesign the data collection method, observe at a different time). Baseline data collection is important in order to measure the impact of the intervention on the interfering behavior. The teachers/practitioners also must decide who will collect the initial data. For example, it might be easiest for a paraprofessional to collect data across the day. The team also may decide that it would be easier to have an objective observer collect data rather than the classroom teacher, who is in the middle of a lesson. Step 3. Determining the Function of Behavior Prior to implementing the intervention, teachers/practitioners interview school staff, family members, and the learner (if appropriate). An important part of determining the function of the behavior is to interview team members about the nature of the interfering behavior. Team members may provide information about the purposes of the interfering behavior in different contexts and different forms of the behavior that serve the same purpose. 8 Prior to implementing the intervention, teachers/practitioners use direct observation methods to hypothesize the purpose of the interfering behavior that include: o A-B-C data (antecedent, behavior, consequence). When determining the purpose of the behavior, teachers and other practitioners also must identify what happens right before the behavior (i.e., antecedents) and what happens immediately after the behavior occurs (i.e., consequences). For example, a teacher gives a direction to a student to line up with the class to go outside (antecedent), the student has a tantrum (behavior), and the teacher allows the student to remain inside to calm o down (consequence). In this example, the behavior appears to serve the purpose of escaping the outside activity. For additional examples of ABC data charts, see Steps for Implementation: Functional Behavior Assessment (National Professional Development Center on Autism Spectrum Disorders); Anecdotal observation. This may involve gathering a running log of the behavior o during observation sessions; and Functional analysis. Once this information is gathered, a functional analysis can be completed that tests the proposed purpose of the interfering behavior against actual behavioral observations. For greater detail on completing a functional analysis, please consult the Functional Behavior Assessment module. Teachers/practitioners identify the function of the behavior as one of the following: o o o o securing attention; accessing tangible items; escaping/avoiding a task or situation; and/or sensory reinforcement. Keep in mind that the same behavior may serve more than one function. For example, a learner with ASD pinching her peer's arm may be doing so to: o o o o cause an immediate response when the peer looks over (i.e., attention); attain a preferred item from the peer's hand (i.e., tangible item); stop an interaction (i.e., escape/avoidance); or seek pleasure in the auditory input provided when the peer yelps (i.e., sensory reinforcement). 9 Using a thorough data collection system to monitor, evaluate, and define the unwanted behavior(s) will make it easier to develop a comprehensive intervention plan to address all functions and teach more acceptable alternative behavior. Step 4. Creating an Intervention Plan Teachers/practitioners clearly write out extinction procedures (e.g., "When the learner does__X____, we will respond by doing ____Y____") by: o preparing a list of possible learner responses to the intervention; and o determining appropriate teacher/staff responses. The first phase of Step 4 is to clearly write out the intervention procedures. Teachers/ practitioners might prepare a list of possible learner responses to the intervention and determine appropriate teacher/staff responses. For example, if a student is raising his/her hand repeatedly and the function is hypothesized to be gaining attention, the teacher can plan to ignore the student's hand raising. Teachers/practitioners define other strategies to be used along with the extinction procedure. An important part of creating the plan is to define how extinction procedures will be incorporated with other intervention strategies. The following list includes other intervention strategies that might be considered. Additional information regarding these strategies is available in separate briefs. o functional communication training (FCT); o differential reinforcement; non-contingent reinforcement; or response interruption/redirection. o o 10 Teachers/practitioners define the extinction procedures that the team will follow such as: o o o o ignoring the behavior; removing reinforcing items or activities; not allowing the child to escape from non-preferred situations; or preventing sensory feedback from occurring. Some examples of how to use extinction procedures based on the four common functions of behavior are provided in the table to the right. The purpose of extinction is to reduce an interfering behavior, but it is very important to also teach or promote a replacement behavior (an appropriate behavior that would take its place). When using extinction, practitioners should determine the appropriate replacement behavior and strategies for promoting it. Options for such interventions appear in the last column of the table. Teachers/practitioners outline an extinction burst safety plan (i.e., what staff/family should do when the behaviors get worse before they get better). It is important to anticipate that the behavior will possibly get worse for a little while before it gets better. This is sometimes called an extinction burst. Planning for a possible extinction burst includes determining an appropriate response. This requires developing a clear plan to handle a possible increase in the interfering behavior. In the above example of a student who is kicking to escape demands, the extinction burst plan 11 would describe what actions to take if the student starts kicking other students. For example, if during the extinction burst, the student kicks even more than usual, the teacher/practitioner simply ignores the kicking and continues with task demands. Teachers/practitioners discuss the intervention with all adults who are with the learner with ASD on a regular basis (e.g., therapists, paraprofessionals, family members). Teachers/practitioners explain the intervention procedures to other students who are in close proximity to the learner with ASD when the interfering behavior occurs (e.g., in the same class, at lunch). Other students also may be alerted to the intervention plan and possible extinction burst. Step 5. Implementing the Intervention Teachers/practitioners wait for the behavior to occur and respond by: o planned ignoring - having the team ignore the problem behavior (e.g., teacher turns away from the student when she screams because she cannot complete the math o problem); denied access - removing reinforcing items or activities (e.g., the CD player is taken o away after the student ignored the aide's request to stop pushing the rewind button; the bubbles are put away after the student grabbed them from his peer); escape extinction - preventing a student from avoiding or escaping a undesirable o task or situation (e.g., not sending a student home for disruptive behavior when the student wants to leave school); and sensory extinction - preventing sensory feedback that is reinforcing an interfering behavior (e.g., consistently blocking a student from turning a classroom light switch on and off repeatedly for visual self-stimulation). Planned ignoring literally involves no verbal contact, no physical contact, no eye contact, and no emotional reaction during or following an attention maintained interfering behavior. While this strategy may be difficult to implement initially or for extended periods of time, consistency is crucial. If a student's disruption increases in intensity or duration, then reinforcing other students for ignoring and tolerating the extinction burst may be helpful. Sometimes complete planned ignoring is impossible. 12 For example, if a student is running off campus because she wants to be chased for attention, then staff must chase her to maintain her safety. In this situation, a focus on providing high quality attention in the learning environment prior to problem behaviors should be emphasized. However, if the student runs away, then the attention delivered during redirection should be minimized (e.g., no verbal interaction, no emotional reaction, minimal eye contact, and least restrictive physical redirection). Watch the data closely to determine signs of improvement. Denying access to preferred items and activities should emphasize a proactive attitude toward environmental management. In other words, attempt to first arrange the environment so that access to specific items and activities are not readily available. If a problem behavior is used to request the item, then simply deny the request or prompt a more appropriate form of communication. If a student gains access to an unavailable item, then a teacher has to consider the pros and cons of physically removing that item from the student. Generally speaking, removing an item from a smaller, younger child is often more reasonable and effective with less risk. Physically removing an item from a larger, older child sometimes poses increased physical risk. Always bear in mind the individual student and consider less physical methods to restrict access. For example, unplugging a computer or placing recess toys in a locked closet will reduce the need for physical interventions around denied access. Escape extinction procedures often pose a difficult challenge to educators. When a student uses a problem behavior to communicate refusal to complete an academic task, it is important to remember that practitioners cannot make' a student read, solve math problems, comprehend a history lesson, etc. However, educators might consider restricting a student's ability to leave the learning setting (e.g., her desk, the classroom, the lab, etc.) until the task is initiated or completed. For some students, this approach can be very effective, especially if the student will follow verbal redirection versus requiring physical redirection. Other students may ignore instruction or sustain disruption to avoid the task for a time longer than school staff are able to keep them in the immediate learning environment. If this situation occurs, consider collaborating with the student's parents to withhold home-based reinforcement until the task is initiated or completed. Lastly, and most importantly, when educators encounter students who use problem behavior to escape or avoid a task or situation, there is a high likelihood that the task or situation is directly highlighting skill deficits of the student. An extinction procedure will not teach a student reading, math, or social skills. When this is the case, 13 a pre-planned set of interventions designed to teach skill deficits and reinforce these skills is required. Sensory extinction procedures implemented in a school setting pose their own set of advantages and challenges. If a student's self-stimulatory behavior requires external stimuli, such as toys, doors, computers, music, videos, and/or the responses of other people, then sensory extinction procedures are generally easier to implement. For example, if a student derives sensory stimulation from repeatedly opening and closing the classroom door, then teaching staff can more easily block this behavior from happening on a consistent basis by holding the door shut. However, if a student's selfstimulatory behavior relies solely on their own actions, such as verbalizations, waving fingers in front of their eyes, hitting parts of their bodies against hard surfaces, etc., then teaching staff will find it very difficult to block these behaviors on a consistent basis. For example, a teacher cannot place a student's high pitch screaming on extinction if the screaming is maintained by self-stimulatory reinforcement (because the reinforcement is occurring internally). In these difficult situations, the most promising interventions to reduce self-stimulation often lie in teaching a student other ways to play, socialize, selfregulate, and entertain himself to meet the function of the behavior. Other promising techniques may include differential reinforcement and designing an engaging curriculum to prevent the child's need to self-stimulate in the first place. When designing the implementation of a specific extinction procedure, it's important to consider the level of actual control practitioners have over the behaviors and the environment, as well as what additional interventions and supports will be required to teach the student specific skills to replace the interfering behaviors. Also, if an interfering behavior serves more than one function, extinction procedures for each function are required. Sometimes the consequences maintaining the behavior are obvious, such as the learner immediately receiving a preferred item when he yells loud enough. However, in other cases the behavior may be maintained by multiple sources of reinforcement. For example, the learner's outbursts in class may be maintained by the teacher's reaction to the disruptive behavior, by a classmates' response, or a combination of both. Similarly, the learner may cry when her mom drops her off at preschool to avoid school, to keep her mother at school longer, to elicit the teacher's concern and attention, or to achieve some combination of all three. It might be important then to identify and withhold several 14 sources so that the effects of each reinforcer on the learner's behavior can be determined. Once the reinforcing consequences have been identified, the next step is to ensure that all adults who interact with the learner are consistent in withholding those reinforcements. Having all adults be consistent is critical for behavior change and absolutely necessary for extinction to be successful. A third step (if appropriate given the learner's needs) is to explain the extinction procedure to the learner. Behavior can decrease more quickly during extinction if the learner is aware of the procedure being applied. For example, if the learner understands to not interrupt the teacher during small group instruction, but instead to raise his hand and wait for the teacher to come over, the strategy may be more effective than having to ignore the learner and deal with the interruption. Teachers/practitioners promote a replacement behavior using a similar intervention approach such as functional communication training or differential reinforcement of other more appropriate behaviors. Although extinction is an effective procedure, its effectiveness is increased when combined with other intervention procedures that also reinforce appropriate behaviors. The reason for this is that while extinction teaches a learner what not to do, it does not teach the learner what behavior(s) to do instead. It is sometimes helpful to ask the question, "What do we wish he/she would do instead of the unwanted behavior in order to achieve his/her goal?" The answer to this question is a potential target behavior to teach or increase by using reinforcement strategies. The teacher/practitioner and/or other team members might identify a replacement behavior to teach the learner what to do instead of engaging in the problem behavior. The target behavior should serve the same function as the problem behavior, be relatively easy for the learner to use, and be recognized by others and reinforced consistently throughout the learner's environment. Each of these strategies can be effective in reducing problem behaviors when appropriately and consistently implemented. However, specific strategies and special circumstances must be considered when implementing each of these extinction interventions in a school environment. If a problem behavior is too intense, or is predicted to become too intense during the extinction burst, then a heavy emphasis on the other intervention approaches described above may need to be done before any attempts at using extinction. 15 Teachers/practitioners respond as planned during the duration of the behavior. Behaviors that are to be reduced by extinction, where the behavior is no longer followed by the usual reinforcing consequences, gradually decrease or stop altogether. As previously stated when extinction is first used, there is often an immediate increase in the frequency of the problem behavior. That is, unwanted behaviors placed on extinction usually get worse before they show improvement. This initial increase in behavior (i.e., extinction burst) usually means that the reinforcers that maintained the problem behavior were successfully identified and withheld (e.g., the team correctly identified that the student's scream was reinforced by having the aide immediately come over to the student-attention; or that the student's aggressive behavior toward the teacher allowed the student to get up from the table and escape). Therefore, this temporary increase, or extinction burst, in the problem behavior may be an indication that the extinction procedure will be effective. However, it is critical that the team be aware of this possible initial response increase (either in frequency or intensity) and should be prepared to continue withholding the reinforcing consequences on a consistent basis. Otherwise the student will never learn how to use an alternative behavior successfully. Another phenomenon commonly associated with extinction is the reappearance of the behavior even though it has not been reinforced. For example, teaching staff in a classroom may have successfully decreased a student's tantrums using a planned ignoring extinction program. However, after three weeks of no tantrums, the student exhibits an intense meltdown that looks very similar to pre-extinction tantrums. This is called spontaneous recovery; however, it is usually brief and limited as long as the extinction procedure remains in effect. Nonetheless, the team should be aware of this possibility or they might assume that the extinction procedure is no longer effective, and may inadvertently reinforce the problem behavior again. Step 6. Collecting Outcome Data In Step 6, teachers and practitioners again measure the topography, frequency, intensity, location, and duration of the problem behavior following the extinction intervention. This process should include getting input from team members as well as making direct observations of the learner in the setting where the behavior occurs. A-BC data (antecedent, behavior, consequence) should also be collected at this time. 16 Gathering thorough data regarding the interfering behavior is an important step in determining if the intervention is working. Teachers/practitioners collect outcome data that focus on: o o o o o what the behavior looks like (topography); how often the behavior occurs (frequency); where the behavior occurs (location); how intense the behavior is (intensity); and how long the behavior lasts (duration). Teachers/practitioners collect data in the setting where the behavior occurs. Data should be collected long enough to determine the effectiveness of the intervention plan. Ensure that baseline measures and treatment measures match regarding types of data recorded, settings, time of day, etc. Intervention evaluation becomes impossible without consistent data throughout the time that baseline data and treatment data are measured. Teachers/practitioners compare intervention data to baseline data to determine the effectiveness of the intervention. Step 7. Reviewing the Intervention Plan After collecting outcome data on the interfering behavior, the next step is to review the effectiveness of the intervention plan. Depending on the response of the learner to the extinction strategy, modifications may need to be made to the procedures. Once modifications are in place, frequent follow-up observations are necessary to determine if the interfering behavior has been eliminated. It also is important to consider if new interfering behaviors have developed in place of the original interfering behavior. All relevant team members meet to discuss intervention data and to determine its effectiveness. Teachers/practitioners modify the intervention plan if the learner continues to exhibit the interfering behavior by: o o o changing the way they respond to the behavior; changing the length of time they ignore or respond to the behavior; expanding the plan to other settings; 17 o o having other team members implement the intervention plan; or adapting the plan to target new behaviors which may have arisen. Teachers/practitioners collect data at least weekly to determine the effectiveness of the intervention on reducing the interfering behavior. Teachers/practitioners identify new interfering behaviors as they arise. Case Study Examples The authors have provided you with two case examples for extinction within this module. Lindsay Lindsey is a twelve-year-old girl with ASD. Her current educational placement is in a self-contained special education classroom with inclusion supports for specific subjects. Lindsey uses full-verbal language to communicate. Yet, her conversational skills are limited. She prefers to discuss her favorite cartoon shows and movies, but she has difficulty participating in discussions on other subjects. In addition, Lindsey frequently asks the adults in her life to say very specific phrases and words. For example, during a reading lesson, she might randomly ask her teacher, "Ms. Stone say, I should pull the cart up the hill.'" During a coloring activity, Lindsey might tell a teacher to repeat the word "immediately." Lindsey may even write the sentence on a piece of paper and insist that the teacher read the phrase out loud. These phrases or words are never related to the current activities. If the teacher attempts to redirect Lindsey back to the presented activity (academic, social, etc.), or refuses to read the scripted phrase, then Lindsey will begin to tantrum, scream, and sometimes destroy school property. After several months, the teachers learned that the fastest and easiest way to redirect Lindsey back to the lesson (and avoid a tantrum) is to say Lindsey's target phrases or words. However, Lindsey's demands for repeating off-topic phrases or words have increased and this behavior has begun to significantly disrupt her ability to stay on task. This behavior also tremendously impedes Lindsey's abilities to appropriately socialize with adults and peers during many school-based activities. In response to the growing concern about this interfering behavior, school staff conducted a functional behavior assessment (FBA). Through the assessment process, 18 teaching staff hypothesized that Lindsey asks teaching staff to say or repeat specific phrases and words in order to gain staff attention, but also as a stereotypical behavior pattern that is likely automatically reinforced. Baseline data reflected that Lindsey demands staff to repeat specific phrases or words an average of 12 times per hour. With this information, teaching staff developed a behavior support plan with the following focuses: o o continue to teach Lindsey appropriate ways to obtain and expandsocial interactions with staff; and do not reinforce Lindsey's disruptive requests to say specificphrases or words. This basic differential reinforcement plan would hopefully continue to: o build appropriate social behaviors; while o simultaneously stopping Lindsey's requests for staff to repeatspecific phrases and words (as well as the tantrums thatfollowed). The extinction component of the plan was to never repeat the specific phrases or words that Lindsey would demand staff to say. Staff could talk about any other topic, promote conversation, redirect to task, play games, etc., but they were not to repeat off-topic stereotypical phrases requested by Lindsey. If Lindsey began to tantrum, scream, or destroy school property, then staff should take Lindsey on a walk in order to allow her to self-regulate while continuing to not reinforce her repetitive requests. Lindsey and all staff were trained on the extinction plan. During the first few days of implementation, Lindsey escalated to tantrum every time staff ignored her requests to repeat phrases or words. Her requests for staff to repeat increased in frequency, her tantrums increased in intensity and duration, and staff took her on several walks per day. After three days of consistent implementation, a noticeable decrease in requesting and tantrum was observed. Two weeks after implementation, data showed an average of ten requests per day and no tantrums when those requests were ignored. Lindsey's requesting had been placed on extinction and was not being reinforced. The decrease in requesting appeared to correlate with an increase in on-task behavior, as well as extended conversations that were less likely to be interrupted by off-topic requests to repeat specific phrases or words. 19 Leighton Leighton is a thirteen-year-old middle school student diagnosed with ASD. She is very verbal and is taught within a general education setting all of the time. Leighton enjoys going to school and math is her favorite class. Lately, her teacher has noticed that when it is time to work independently, Leighton makes several mistakes on her worksheets and raises her hand for help. As a consequence, the paraprofessional or teacher comes over to offer prompts, cues, and encouragement. Only after the time-consuming help and attention, however, does Leighton correctly solve the math problem. Both the teacher and paraprofessional are certain that Leighton knows how to complete the math problems, and after conducting an FBA, it seems that their instruction, attentive reactions, and encouragement are positive reinforcement for the incorrect responses. After a meeting, the team decided to place the Leighton's incorrect math responses on extinction from staff attention. The team outlined the steps beforehand on how to implement extinction and what consequences to provide contingent on the target behavior occurring (i.e., Leighton independently completing the math problems without mistakes). It was also decided that slight modifications would initially be made to Leighton's worksheets, such as reducing the number of problems and only having content that Leighton knew how to do from prior observations. As Leighton's independent work improved, the number and complexity of problems would be increased. The next time that Leighton was instructed to work on her math sheet, she glanced at the teacher and raised her hand for assistance. With the extinction plan in effect, the teacher ignored Leighton's request and continued working at her desk. Leighton then looked over at the paraprofessional to gain her attention and similarly, the paraprofessional remained seated scoring worksheets. Leighton then made several verbal statements to try to gain a response from either adult, such as saying, "I can't do math," or "I can't remember how." Leighton then marked her paper and put her head down on the desk occasionally sighing or grunting, while both adults continued to ignore her behavior. While her behavior slightly intensified (i.e., extinction burst), no serious escalations occurred and the teacher and paraprofessional both felt comfortable in continuing with the extinction procedure. 20 However, had Leighton demonstrated a more aggressive or disruptive behavior in response to the extinction, such as throwing her chair or hitting her head, the team would have met immediately to develop an extinction burst safety plan. Options might have included adding more modifications to Leighton's' worksheet, introducing additional intervention procedures (e.g., self-management, differential reinforcement), using pull-out time to have Leighton work independently, but in a more controlled environment and then bringing her back into the classroom. However, these additional steps were not necessary. After 15 minutes of not working, Leighton picked up her pencil and began to independently complete her math sheet. The teacher then walked around the class and stopped at Leighton's desk to praise her for working so nicely and correctly solving all the problems. Encouragement and praise continued to be delivered contingent upon Leighton completing the work by herself. After one month of this procedure, incorrect math responses declined to approximately zero per class session and modifications to Leighton's worksheets were no longer necessary. Summary o Extinction is a procedure in which reinforcement of a previously rewarded behavior is stopped. o Extinction of positively reinforced behaviors does not allow the learner to access positive reinforcers after a problem behavior. o Extinction of negatively reinforced behaviors does not allow the learner to escape/avoid undesirable consequences after a problem behavior. o Extinction of sensory behaviors does not allow the learner to access sensory-based reinforcement after a problem behavior. o Extinction yields a gradual, not an immediate, reduction in behavior. o A problem behavior placed on extinction may show an initial increase in frequency, intensity, and/or duration (i.e., extinction burst) following the removal of reinforcement. It is not uncommon for the behavior to gets worse before it improves. 21 o Spontaneous recovery may occur with extinction in which there is a reappearance of the problem behavior after a period of time in which the behavior has not been reinforced. o Resistance to extinction may occur, in which the problem behavior continues to occur at similar levels. Variables most likely to cause this phenomenon are: o schedules of reinforcement; o amount, number, and quality of reinforcers provided; o number of previous extinction trials; and o effort required from the learner to make the response. o It is more effective to combine extinction with other intervention procedures, particularly since extinction does not teach the learner what to do instead of the problem behavior. Other suitable interventions include: o functional communication training; o non-contingent reinforcement; o differential reinforcement, and/or o self-management (see other modules). Be sure to identify and withhold all sources of reinforcement for the problem behavior. It is critical that all adults in contact with the learner be consistent in o withholding the reinforcement so that they do not accidentally reinforce the occurrence of the problem behavior. o Be sure to plan for extinction-produced aggression o It is not recommended to use extinction for behaviors that are likely to be modeled by others or for behaviors that are harmful/dangerous to self or others. Download PDF Checklist For Extinction: http://www.autisminternetmodules.org/up_doc/ExtinctionImplementationChecklist.pdf 22 Discussion Questions 1. When should an extinction procedure be used? A correct answer should include a statement such as: o Extinction should be considered when trying to reduce a problem o behavior that is reinforced by positive, negative, or sensory consequences. Extinction should be used along with other reinforcement strategies, such o as functional communication training, differential reinforcement, noncontingent reinforcement, self management, or response interruption/redirection. Other reinforcement-based procedures may want to be tried first and if there is no change to the behavior, then extinction should be considered. 2. What steps should occur in preparation for implementing an extinction procedure? A correct answer should include a statement such as: o o o o Data should be taken by all team members that are familiar with the learner to determine the function of the problem behavior. A description of the problem behavior and replacement (or target) behavior should be adapted into a form that the learner (if appropriate) can comprehend. Examples include simple written descriptions and pictorial descriptions. Before starting the extinction procedure, steps of how to follow through with the extinction procedure, the setting(s), and the person(s) responsible for implementing and monitoring data, and whether other intervention procedures will be used, as well, should be decided. An extinction burst safety plan, or how to respond should the problem behavior become worse before improving, needs to be developed. 3. What should you do to increase the likelihood that the extinction procedure will work? A correct answer should include a statement such as: 23 o o o o Take detailed data to identify all functions for the problem behavior (e.g., when does it occur, with whom, under what situations, what does the behavior look like). Make sure that all persons (both adults and peers) who come into regular contact with the learner consistently withhold reinforcement when the problem behavior occurs. Include intervention strategies to teach the learner what to do instead of engaging in the problem behavior. Select replacement behaviors that the learner is able to do (and therefore can be taught within a short period of time) and that will be reinforced by others on a consistent basis. o Aim to be preventive so that the learner has no reason to engage in the problem behavior (e.g., remove triggers from the environment, select powerful, motivating reinforcers to encourage the use of the desirable behaviors, remove or mask the consequence to the problem behavior). 4. Describe a learner that you think would benefit from an extinction procedure. What skills need to be targeted for intervention? On the other hand, describe a learner with ASD that you think would probably not benefit from an extinction procedure. What characteristics of this learner make it less likely that an extinction procedure would be beneficial? Answers to this question will vary. Each answer should be supported by content derived from the module, but should vary based on the individual learner being described. 5. Continuing your answer to Question 4, think of a learner with ASD that you feel would benefit from an extinction procedure. How would you respond if the learner's behavior became worse or did not respond to the extinction procedure? Justify your answer based on the learner's individual characteristics. Answers to this question will vary. Each answer should be supported by content derived from the module, but specific answers do not have to come directly from the module as long as they are justified based on the individual 24 characteristics of the learner. When it comes to individualizing an intervention, creativity should be encouraged as long as the proposed ideas seem feasible, humane, and ethical.