Myth of the West Reading

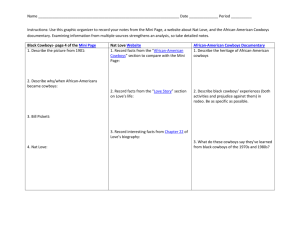

advertisement

OSWEGO HIGH SCHOOL Department of Social Studies: U.S. History The Myth of the American West Excerpts taken from The Guardian (modified by Jachimiec) The heroic myth of the American West is much more powerful than its actual history. To this day, false beliefs about cowboys prevail: that they were (and are) brave, generous, unselfish men; that the West was “won” by noble white American pioneers and soldiers fighting the red Indian foe; that frontier justice was rough but fair; and that everything in the natural world from the west bank of the Missouri to the Pacific Ocean was there to be used by Americans to further their wealth. These absurd but solidly rooted fantasies cannot be pulled up easily. People believe in and identify themselves with these myths and will scratch and kick to maintain their western self-image. The rest of the country and the world believe in the heroic myth because the tourism industry will never let anyone forget it… In the real West, people see only those qualities that fit the limited concept of individual freedom, independence, toughness and pioneer “spirit.” The easiest way to do this is by wearing clothes that symbolize all these presumed virtues: a ten-gallon hat, boots and spurs, a pearl-buttoned yoked shirt and blue jeans. Western Day celebrations, shows and rodeos often declare obligatory western attire for local inhabitants so tourists are treated to hundreds of fake cowboys limping around in high-heeled boots. Architecture helps preserve the myth of the West too. A visit to southwestern tourist sites will reveal log mansions, adobe structures in Santa Fe (fake buildings made of stucco over chicken wire and plywood) and the still-popular false-front stores of many small western towns. Teepees stand in front of shops selling “Indian” crafts made in China. All of these structures carry the message that the West of the 21st century is still the West of 1885. No one in today’s West wants to know that most fur trappers who originally settled the area were rough, illiterate men, who took advantage of tribal women to discover the best trapping areas and trading opportunities. Their goal was financial success and to retire wealthy and respected back in the East. The highly detailed illustrations of artist John Clymer, used on the covers of many western history books, show these big-chinned, clean, buckskin-clad trappers on handsome horses in stunning landscapes. Sometimes there is an Indian in the painting, but usually in the background or in a subordinate position, often with a receding chin – subtle reinforcements of the myth of white people’s superiority. The trappers, like their successors the cowboys, were a force in the West only for about 20 years before the beaver market crashed. The fur trade was the earliest episode in the boom-and-bust economy that characterized the region. Meanwhile, cowboys, many of them ill-paid and armed Texas teenagers, were not revered in their brief years after the Civil War for driving cows up trails to feeding pastures. They did not call themselves cowboys but cowhands, punchers, buckaroos, wranglers and waddies. They were hired hands, under the control of older foremen, themselves employed by investors. The myth, of course, contains no whiff of homosexual behavior on the part of these cowboys who often shared beds in addition to work and danger. Nowadays, far from the romantic myth Americans cherish in Hollywood westerns, “cowboy” has come to stand for a shoddy, don’t-give-a-damn construction worker with a rude, boisterous attitude. Beginning with Ronald Reagan’s campaign for the presidency in the early 80’s, images associated with the word “cowboy” have also been used by politicians who seek to promote a certain persona of themselves. These political “cowboys” do not portray themselves as decent, stalwart protectors of innocent people and cattle, but rather as aggressive OSWEGO HIGH SCHOOL Department of Social Studies: U.S. History bullies who force weaker people to submit to them. As a result, the West has recently come to symbolize the policies and character of the United States – a country increasingly hated and distrusted by the world at large. In addition to the cowboy, one of the West’s favorite sub-myths is the prostitute with the “heart of gold” who has been forced into the trade by tragedy and poverty. In westerns, she treats her customers fairly, becomes the intimate confidant of powerful men, owns half the town, gives (anonymously) to the church and eventually marries a respectable rancher. Anne M. Butler blew this myth apart in her book Daughters of Joy, Sisters of Misery. In reality, prostitutes were poor and wretched, with no chance to escape the life once they were in it. They were vulnerable to alcohol and drug addiction, blackmail, disease, unwanted pregnancies, brutality, arrest and jail. If they married at all, it was usually briefly to low, fleeting men with as many problems as they. Western newspapers used prostitutes as the butts of foul humor, and they did not hesitate to name names. Small wonder that so many of these women killed themselves! And what of the relationship between whites and Indians? The myth of the West has typically reduced the complex mix of Native American tribes to absurd simplicity, pitting conquering white settlers and the U.S. army against generic but “fiendish, cruel and bloodthirsty” Indians. One reason the Battle of Greasy Grass (Custer's Last Stand) so catches the American imagination is because it could be easily grasped and because it illustrated basic prejudices: a few white American soldiers on one side, a large mass of red Indians on the other. This battle has achieved a kind of disgusting popularity thanks to the Anheuser-Busch brewery of St. Louis, which in 1896 printed photographs of Cassily Adams's painting “Custer's Last Stand,” showing General Custer under pressure in the center of the battle brandishing his sword. The painting was crammed with historical errors but it too fueled the myth of the West. After all, Anheuser-Busch sold more than a million of the prints, which decorated bars and homes from coast to coast. Although white westerners today like to believe there were only a few groups of backward Native Americans in “the golden West” when Europeans arrived in the New World, there were, in fact, between 850,000 and one million Native Americans in America– people who had successfully practiced their own cultures for at least 12,000 years. In the 18th and 19th centuries, tribes were on the move, eager for the horses of the southwest, pushed out of their old territories in the East by other tribes and encroaching European/American civilization. By the 1880s, the tribes, pushed off their lands, riddled with smallpox, tuberculosis and venereal diseases, were starving and tattered. Nevertheless, there arose in the eastern part of the United States a widespread belief that the Native Americans, like the bison, were vanishing, and then not only painters but photographers rushed west to capture the exotic essence of Native Americans. From the 1860s onward, cabinet card photographs of Native Americans were hugely popular. The Native American quickly became a commercial commodity, eventually used to sell everything from sports teams to canned peaches. More than a few of the photographers used fake props and costumes to enhance their images; real Native Americans were, by the 1880s, demoralized and clad in dirty rags. The sense that they would soon be gone goaded museums and collectors to start gathering up artifacts: baskets, beadwork, pottery, arrows, cradleboards. This habit became ingrained in westerners who commonly seek and pick up arrowheads when they come across them. Thus, by the early 20th century a kind of romantic, picturesque movement began to show Native Americans as a handsome, noble and tragic (though still generic) people. This sympathy for the conquered persists – although now it is mixed in with some white Americans’ quests for spiritual healing and psychedelic drugs said to lead users to serenity and health. One look at conditions on most reservations will show that serenity and health are anything but hallmarks of today’s Native Americans. The other side of the “noble Indian” experience is places like Gallup, New Mexico, where Native Americans spend their Saturday nights in the grip of alcoholism – a disease that ruins many of their lives across the country.