AcadAffairs_Affordability_Draft_2_24_15

advertisement

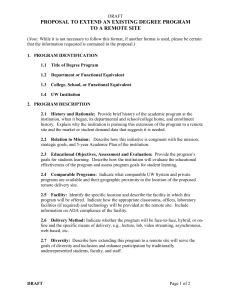

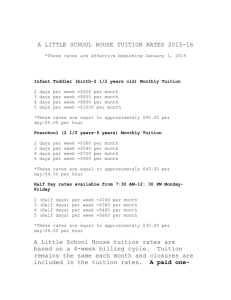

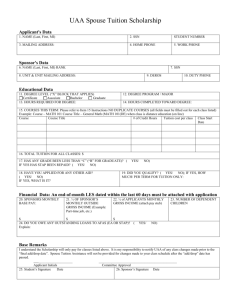

AACP Academic Affairs Committee Affordability Sub-Committee Report Goal: Determine how can we increase perceived value of pharmacy education, make pharmacy education more affordable, and/or help students manage/decrease their debt burden Dejuvoo CHANGES IN HIGHER EDUCATION ENROLLMENT Higher education enrollment changed in the 1960s as a result of changes in the labor market requirements, the entrance of baby boomers, and increases in state and federal funding for higher education. In 1960 about 45% of high school graduates enrolled in post secondary education program (ie. College or trade school) compared to 70% in 2009. This corresponded to roughly 4 million enrolled students in 1960 and 20 million in 2009. The characteristics of the enrolled students also changed. The proportion of non-traditional students (over 24 years of age) increased from 28% in 1970 to about 42% in 1990. Similarly the proportion of part-time students went from 32% to 42% over this same period. These proportions have remained relatively constant since the 1990s. The increased proportion of high school graduates attending college has resulted in higher attrition and the need for remedial course work as lesswell-prepared students entered college (Baum, Kurose, and McPherson, 2013). COLLEGE ATTENDANCE AS AN INVESTMENT The median salary gap between college graduates The impact of the changing labor market on higher education is further illustrated by the observations that the median salary of college graduates in 1990 was 1.6 times higher than that of high school graduates. The gap in median salaries increased to 1.87 by 2010 (these figures were adjusted for inflation) (Baum, Kurose, and McPherson, 2013). INTRODUCTION Prior to the 1960s undergraduate education was largely delivered by private non-profit colleges and public four-year institutions financed by state governments. The strong economy following World War II gave state governments the confidence to expanding access to higher education to the growing (baby boomer) population. Prior to the 1960s, the federal government’s role in financing higher education was largely limited to GI benefits. The 1965 Higher Education Act and the 1972 Basic Educational Opportunity Grant program, the forerunner of the Pell Grant program, altered the federal government’s role in financing higher education. In the 1970s the increased number of students and the increased educational offerings (and increased number of institutions providing higher education) resulted in increased educational spending. The formula for financing higher education consisted of federal money providing grant aid to students, state money supplementing operating expenses with the remainder provided by students/families in the form of tuition (Baum, Kurose, and McPherson, 2013). 1. Define affordability The perception of value is based on a consumer’s evaluation of the price they pay for a product or service and the benefit or utility that they derive from consuming or using the product or service. Higher education has many stakeholders that could be considered consumers. These include students/alumni, legislators, donors, employers, and the consumers of research generated by universities. The student is the focus of this committee report. Before even considering whether or not to attending college, the student must believe that the price paid for a college education can be covered by his/her current budget (which includes salary, loans, grants, and scholarships). Changes in household income, state and federal funding, and the cost of higher education will be reviewed to better understand issues of affordability and value. Then a two-part production function of higher education is described to isolate student-related costs and a taxonomy of students’ educational experience is presented to understand specific areas where perceived value can be influenced (positively or negatively). Both tuition and median household incomes have increased over the past 30 years. However, a larger portion of income was taken by tuition in 2011 compared to 1981. The average in-state tuition (adjusted for inflation) at public four-year institutions increased from $2,242 in 1981 to $8,244 in 2011 (4.4% higher than the inflation rate). Private institutions saw a similar increases from $10,144 to $28,500 (in 2011 dollars). The median household income in 1981 was $23,390 and $50,502 in 2011, so public non-profit tuition accounted for 9.6% of household income in 1981 and 16.3% in 2011 (US Dept of Commerce; Money Income of Households, Families, and Persons in the United States: 1981; Current Population Reports: Consumer Income, Series P-60, No 137; March 1983, page 1) and (US Dept of Commerce; Household Income for States: 2010 and 2011; American Community Survey Briefs; ACSBR/11-02; September 2012; page 1). Part of the tuition increases may be explained by the fact that state funding has not kept pace with enrollments. The proportion of revenue provided by state governments to public institutions has steadily decreased from 44% in 1980 to 38% in 1990 and 22% in 2009 (Baum, Kurose, and McPherson, 2013-ref 39). State appropriations per full-time student dropped from $9,300 in 1999 to $7,100 in 2009 (adjusted to 2010 dollars) (Baum, Kurose, and McPherson, 2013-ref 41). Based on data collected by the State Higher Education Executives Organization, the 1997 state appropriations per student were $7,134 and tuition was $3,232 (total revenue per student $10,366). By 2007 state appropriations dropped to $6,773 per student and tuition increased to $3,845(total revenue per student $10,618) (McPherson and Shulenburger, 2010).—THIS IS INFORMATION FROM ANOTHER SOURCE. Based on these figures once could conclude that higher education has become less affordable over the past 30 years. However, students don’t necessarily pay the full list price. The difference between the published and paid tuition in made up by grant aid. The average grant award per student across public and private institutions in 1981 (adjusted to 2011 dollars) was $2,490 compared to $6,994 in 2011. Total federal spending from the Pell Grant program, tax credits and deductions was $53.3 billion in 2011-12, an increase from roughly $23.1 billion in 2007-08 (adjusted to 2011 dollars). What is the cause of these increases? The Cost Disease and the Revenue Theory theories have been used to explain rising costs in higher education. Cost Disease Theory is based on the idea that production increases can be achieved in some industries through technology advances. Increasing productivity in labor-intensive service industries, such as higher education, requires increased human resources to avoid a corresponding decrease in quality (Archibald and Feldman, 2008). If the production output of higher education is the number of graduates, then you cannot increase production (i.e. enrollment) without decreasing quality or increasing personnel costs. Clinical faculty have a choice of working in practice or academia, thus schools and colleges of pharmacy must offer higher wages to attract faculty. The Revenue Theory of Cost described by Bowen (1980) is based in the assumption that in a non-profit environment revenue generated in a given time period determine how much can be spent. Bowen claimed that higher education costs are not determined by technological requirements or some standard of need, but by available revenue. Generally speaking, institutions of higher education will maximize educational quality and prestige (which require spending to obtain the best teachers and facilities). Institutions will maximize revenue by increasing tuition to maintain quality if education prestige or quality are jeopardized (Archibald and Feldman, 2008). a. Production model and operational efficiency (Kem) It is easy to get lost in the multitude of facts and figures used to describe the rising costs of education and increases in tuition. Policy makers and the media often assume that rising tuition is a result of rising costs. However, this observation may actually result from a change in the composition of the revenue stream rather than simply increased costs (McPherson and Shulenburger, 2010). A brief economics lesson is in order to better explain this point. Costs are born by the producer and prices are born by the consumer. In a competitive market, the price must cover the cost of production plus a nominal profit, thus there is a direct relationship between cost and price. In higher education the relationship between cost and price is not so clear because the higher education revenue stream can be comprised of tuition, government support, sales of goods and services, indirect research support. The composition of the revenue stream may vary widely between public non-profit, private non-profit, and public for-profit organizations. For public intuitions, tuition increases as state appropriations decrease. The contribution of state appropriation as a percent of total revenue for public research institutions dropped from 54% to 46% between 1987 and 2006. During this same period tuition increased 132%. The tuition increase generated slightly more revenue than that lost by state cutbacks (McPherson and Shulenburger, 2010). When adjusted for inflation, total revenue (tuition plus state appropriations) has increased 0.45% to 0.84% per year since 1996 (McPherson and Shulenburger, 2010). A two-part cost model will be used to examine and discuss cost associated with pharmacy education in this report. The model was originally created to help policy makers understand the cost structure of public research universities (McPherson and Shulenburger, 2010). University costs can be divided into 1) cost centers that generate their own revenue such as research, clinical services, residence halls, dining facilities, athletics, bookstore and other retail outlets and 2) the costs of student education that is paid for by a combination of state appropriations, tuition and philanthropy (McPherson and Shulenburger, 2010). All of these areas contribute to the cost of running an institution of higher education, whether or not they generate revenue. However, the cost centers that generate their own revenue are expected to be self-sustaining or revenue generating. This report will focus on the second part, the cost of student education. Michael Staton created a taxonomy that describes the component parts of higher education focusing on the student’s educational experience. The four main components include the 1) Component Loop, which includes content authoring and production; content transfer; and content pathways and sequencing; 2) Access to Opportunities, which includes a signal of achievement velocity; a credential of accepted value; and an affiliate network; 3) Meta-content and Skills, which include models of thinking and doing; performance feedback leading to mastery; and enduring monitoring, coaching, apprenticeship, and supervision; and 4) A transformative Experience, which consists of a rite of passage; a personal platform; and a culture of personal exploration. The components of this taxonomy are accomplished through didactic and experiential education, extracurricular activities and other processes. These components are also the student services areas for which public non-profit, private non-profit and public for-profit institutions may compete for students. Note that the taxonomy does not include the first component cost centers that generate their own revenue. Education as a production function. The inputs to the production function of higher education includes human resources, educational technology, resources associated with experiential education, and resources necessary for extracurricular activities. Graduates are the output of the production function. INSERT AACP DATA TABLE COST PER GRAD TUITON PER GRAD b. Discussion of affordability and value (Jean/Kem): “I wouldn’t go into in pharmacy if I had to do it all over again” INSERT AACP DATA TABLE AACP/ACPE Standized Student Surveys Would Study Pharmacy Again Year 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 89.7% 88.0% 88.6% 87.4% 84.7% Would Not Study Pharmacy Again 6.9% 8.0% 8.2% 9.5% 11.4% 2012 2013 2014 81.8% 83.9% 81.8% 13.9% 12.1% 14.0% c. Discussion of affordability and value (Jean/Kem): “Joint degree options“ A number of pharmacy schools have try to make degree attainment for efficient by combing degrees. The joint degree options decrease the amount of time required to obtain the two degrees individually. This may save actual tuition and fees and certainly decreases the opportunity costs of being in school. Based on the AACP Summary of Financial Data for the 2012-13 fiscal year, 25 schools offered joint PharmD/PhD progams with an average enrollment of four students; 37 offered joint PharmD/MBA programs (average enrollment: 14); 13 offered joint PharmD/MS programs (average enrollment: 2); 13 offered joint PharmD/MPH programs (average enrollment: 4); and 6 reported offering other joint degree programs. Potential references for this section: Public Mandates, Private Markets, and Stranded Public Investments (Kelly and Carey 2013 Chapter 10) d. Services that could be added to add value (Jean) i. Career counseling ii. Mentoring programs iii. Anything that would add value for students and faculty and staff e. Production model and operational efficiency (Kem) i. Operational efficiency 1. Eliminate waste 2. Applying CEA to Higher Education (Kelly and Carey 2013 Chapter 3) Discuss the cost per graduate in schools of pharmacy over the years. After the economic downturn of 2008, several large research universities hired national consulting firms to review their operations and recommend cost saving strategies. Although the consultants did not address the teaching or research endeavors, they did identify several drivers of inefficiency within higher education. Namely, redundant systems, unneeded administrative complexity, lack of standardization, and misaligned incentives. Examples of redundant systems within a department, college or across the university include bookkeeping systems, IT/email systems, and other data collection systems. Hierarchical growth, or administrative bloat as it is sometimes called, occurs for a number of reasons including the growth of complex systems, as a reward for long-time employees, and to address external mandates to name a few. A 2010 report by the Goldwater Institute found that inflationadjusted spending on higher education administration increased 61% over a 14-year period ending 2007 compared to a 39% increase in instructional spending over the same time period (Greene, Kisida and Mills 2010). Lack of standardization comes down to purchasing power. Many of the universities cited in the chapter didn’t have central purchasing or prime vendors and were unable to negotiate volume discounts on everything from computers to paper to teaching and research supplies. The consultants also highlighted the decision-making paradox in higher education. Both tangible and intangible costs exists for making the wrong decisions in higher education, however fewer penalties exist for making no decision or postponing decisions. This coupled with the strong tradition of shared governance makes it easier not to make a decision in higher education compared to a corporate environment. Additionally the common cost-cutting techniques used when a university is facing budget cuts such as across the board cuts, hiring freezes, salary cuts/furloughs, cutting entire programs or departments, and student service cuts often lead to greater inefficiencies, low moral, and fail to address the longterm overall performance of the institution. Because institutions of higher education are mission-driven, non-profit organizations with sometimes-divergent charges of teaching, research, and service, it is not common to look at costs, revenue and output from a production function framework. Thus it is not always common to identify the specific costs or output for a specific endeavor, making it difficult to assess efficiency and identify strategies for achieving economies of scope and scale. Rethinking the Cost Structure of Higher Education (Kelly and Carey 2013 Chapter 5) Other potential resources: The Roles of Public Higher Education Expenditure and the Privatization of Higher Education on US States Economic Growth (ASHE Chapter 16) Resource Allocation (ASHE Chapters 22&23) National Models for College Costs and Prices (ASHE Chapter 26&28-32) 3. Practicing/working at top of licensure 2. Rethinking Curricular Models BACKGROUND The types of higher education institutions and the delivery mechanisms have changed over the past 50 years. Community colleges (i.e. 2-year institutions) accounted for 24% of higher education enrollment in 1963 and 48% in 2009 (Baum, Kurose, and McPherson, 2013-ref 50). Historically higher education was provided by public non-profit or private non-profit institutions. By 2001 private for-profit organizations had entered the market, accounting for 6% of the enrollment. Their market share increased to 12% by 2011. While only accounting for 12% of enrollment, for-profit institutions account for 21% of Pell Grant dispersements (Baum, Kurose, and McPherson, 2013-ref 53-54). The delivery of higher education varies widely from large lecture-based freshman/sophomore courses taught by graduate students in large private and public institutions to smaller classes at smaller institutions to a production model at large for-profit institutions were specialist design syllabi and course materials centrally that are delivered locally by professionals in the field. (Baum, Kurose, and McPherson, 2013 and ref 57). There has also been a shift from full-time tenure track faculty to non-tenure-tract and part-time and adjunct instructors. Instruction by full-time faculty dropped from 80% in 1970 to 51.3% in 2007. The proportion of non-tenuretract faculty grew from 18.6% in 1975 to 37.2% in 2007. In pharmacy, the introduction of the entry level Doctor of Pharmacy degree has resulted in an increase proportion of non-tenuretract clinical faculty (Baum, Kurose, and McPherson, 2013-ref 58). The impact of these changes on the quality of education is not know. Technology is also changing the way education is delivered. Online and computer-assisted instruction as well as interactive internet based connections such as Skype expand access to education. a. Review of curricular models (Jean) i. Pharmacy 1. O-6, 1-5, 2-4, 2. Year-round 3. Modular 4. Online ii. Other models available in health sciences b. Role of online education (Kem) i. Prepharmacy ii. Pharmacy professional curriculum Potential References for this section Classes for the Massses (Kelly and Carey 2013 Chapter 7) Disruptive Technologies and Higher Education, Next Generation Delivery Models (Kelly and Carey 2013 Chapter 9) c. Shorten curricula (Jean) i. Clayton Christianson – Disruptive Innovation ii. Allow for PLA Potential References for this section Beyond the Classroom, Alternative Pathways for Assessment and Credentialing (Kelly and Carey 2013 Chapter 8) iii. Examine pre-pharm iv. Review necessary competencies d. Decelerate curricula (Jean/Kem) i. How to deal with interwoven curricula Potential References for this section Unbundling the College Experience (Kelly and Carey 2013 Chapter 6) e. Using consortium model i. SABER ii. Medportal 3. Helping students be consumer savvy (Kem) a. Loan selection and management b. Personal financial management Potential References for this section Do Student Borrow Too Much or Not Enough (ASHE Chapter 15) Year % Who Borrowed Money 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 89.3% 88.4% 87.4% 88.7% 88.7% 88.7% 90.9% 2014 89.2% Year 2007 2008 2009 Percent working any hours 71.0% 73.0% 71.1% Percent workign over 20 hours 6.9% 6.5% 6.9% 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 Year 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 68.5% 65.3% 66.5% 79.4% 80.7% Percent working any hours 82.1% 82.3% 80.8% 80.3% 77.6% 77.1% 85.7% 87.0% 5.3% 5.5% 6.9% 7.8% 8.0% Percent workign over 20 hours 15.5% 14.8% 14.6% 13.2% 13.1% 14.1% 14.2% 14.0%