Can higher education be based on nonviolence

Can higher education be based on nonviolence?

A group of students draw accounts of the educational journeys they have made, and then each explains what has been drawn to others in the group. These accounts say so much about the challenges they faced before they could come into higher education, or about the role of advantage in ushering them onto the next level of study.

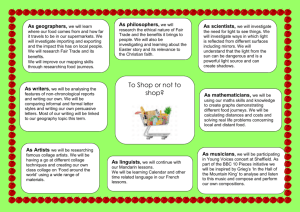

As they listen, the students extend their awareness of the range of possible lives. Those who have not thought much about disability of what it means to be gay, or even about the challenges faced by women in education, or of growing up in a country wracked by war, now find themselves engaging with the ways in which these experiences have shaped others.

Imagine if higher education was a place in which those who enter bring in these experiences and what they have learnt in response to those experiences. Imagine if higher education was seen not as a route out of poverty in rural areas or townships, but as a tool for transforming such areas. Imagine a society that truly could accommodate the full diversity of experience, and marshalled the full potential for thinking and creativity of its citizens.

Achieving such possibilities is the task that ICON is presently pursuing within the Durban University of Technology. At present the ICON Director, Crispin Hemson, is leading the piloting of a new first year course, the Cornerstone module, with a group of senior students and some staff members.

The Design of the Cornerstone module is based on the idea of journeys. It focuses on the wide variety of journeys that we take in society. Early in the pilot four people connected with the

University, as staff, students or ex-students, spoke on a journey they took. The journeys have been journeys of education, physical journeys, or journeys of self-acceptance. Listening to these accounts brings a sense of privilege at understanding the richness of resources that people bring into the institution, and questions as to the extent to which universities draw on such resources.

From a different perspective, this can be seen as postcolonial education. While acknowledging fully the role of our history in forming our society, it operates on a basis of a set of assumptions totally different to those of colonialism and apartheid. While those systems made the lives of the majority of people hard, in all contexts where such people live there are resources and understandings that can inform the lives of all citizens. It treats with respect the many diverse ways people have responded to those contexts, and encourages their questioning and creativity in addressing the challenges that modern society faces.

To do this work, we need to build a sense of safety and trust in the classroom, in a society where there is ongoing violence and insecurity. Students comment on how they become more open with each other, and the need to feel safe to be able to do that. Building trust is central to nonviolence within education; we do so in quite practical ways by spending time at the beginning of the programme in negotiating agreement on the values that underpin our time together.

This work falls within the General Education initiative of DUT. It aims not to replicate the work of discipline-specific programmes, but rather to extend that work and to assist in integrating what is learnt in those programmes with society more generally.

We ensure that we develop attentive listening through the educational work; part of this entails seeing others as worthy of our respect and attention