Help - Mapping Writing

advertisement

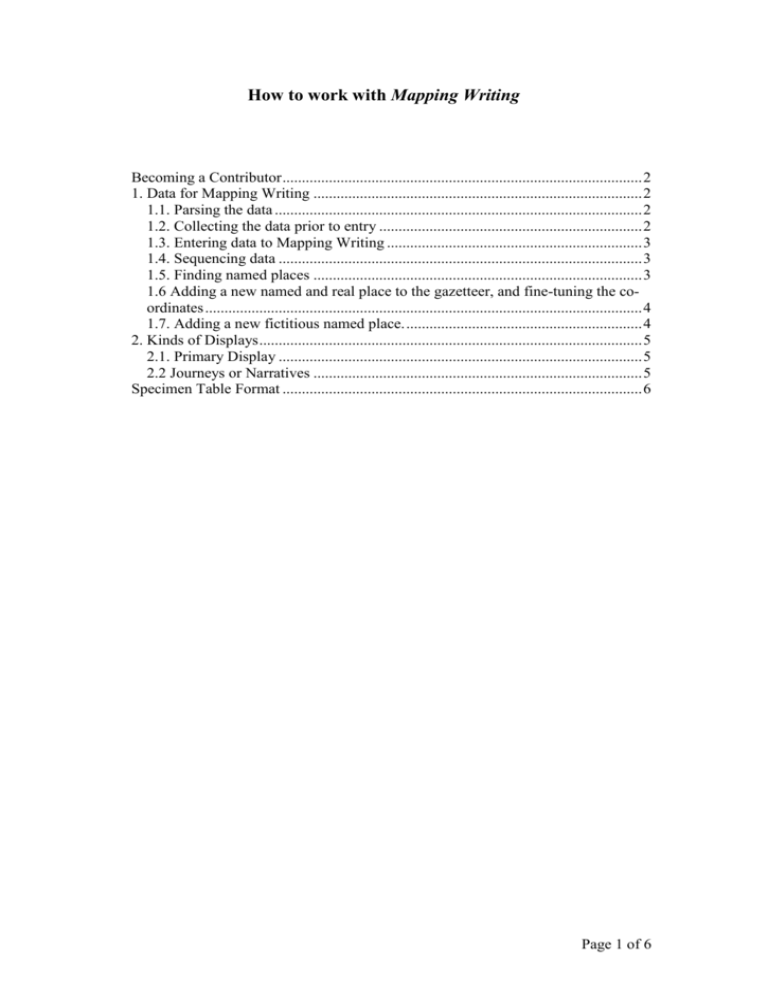

How to work with Mapping Writing Becoming a Contributor ............................................................................................. 2 1. Data for Mapping Writing ..................................................................................... 2 1.1. Parsing the data ............................................................................................... 2 1.2. Collecting the data prior to entry .................................................................... 2 1.3. Entering data to Mapping Writing .................................................................. 3 1.4. Sequencing data .............................................................................................. 3 1.5. Finding named places ..................................................................................... 3 1.6 Adding a new named and real place to the gazetteer, and fine-tuning the coordinates ................................................................................................................. 4 1.7. Adding a new fictitious named place. ............................................................. 4 2. Kinds of Displays ................................................................................................... 5 2.1. Primary Display .............................................................................................. 5 2.2 Journeys or Narratives ..................................................................................... 5 Specimen Table Format ............................................................................................. 6 Page 1 of 6 How to work with Mapping Writing Becoming a Contributor To be a contributor, you will need a Literary Encyclopedia user identity. Please click on the following link and make a user account. Please complete the first two pages and do not neglect to enter your forename(s), surname (and institutional address if any) as these will appear in the by-line of the contributions you make. If your university is a subscriber to The Literary Encyclopedia, please use your institutional email address. Login to Mapping Writing with the username and password you have created for The Literary Encyclopedia and then click on Apply. A message will be sent to the relevant editor and once your application has been approved you will be notified and will be able to start making pins. As you make each pin, your editor will be sent an email so she or he can check your work. 1. Data for Mapping Writing 1.1. Parsing the data The basic datum of a literary or cultural map is the map pin which relates a place to certain kinds of information the passage which represents it the text which contains the passage (title, publisher, year of publication) the time of the representation according to the text metadata which is useful for cataloguing (country of origin, date of first publication, genre of text, gender of author). In most cases this will be derived from the file in The Literary Encyclopedia . Please note also that a) nearly every mention of a place since c. 1650 will also be related to a particular time (which may be stated or implied – e.g. “three weeks later”), and that sometimes a place is implied rather than mentioned explicitly (for example, London as a point of departure and return in the voyages of Robinson Crusoe). Where a place is implied, it may be necessary to create a pin so as to have a terminus for a journey (see under “journeys” below) even when the text does not explicitly mention the place. 1.2. Collecting the data prior to entry It may be useful to use a table form in a word-processor or spread-sheet to collect basic data as one reads the text, then open the interface and add the data to Mapping Writing. This two-step procedure tends to assist the contributor in checking that all Page 2 of 6 How to work with Mapping Writing the information is to hand and correctly located. It is not necessary, however, to complete mapping a whole work in a single session; completing the work in several different sessions is usually more pleasing. There is a specimen table format at the end of this document. 1.3. Entering data to Mapping Writing The application has been designed to step you through in an intuitive manner. Select your Work and then select under the Works menu the option to “Add or view all representations.” Click on the option to “Add a representation” and follow the prompts. 1.4. Sequencing data The default sequence of entries is the sequence in which they are entered, which will usually be the sequence in which they occur in the text. Since some pages may mention or represent more than one place, page numbers are not good enough for this sequencing and the system adds a sequence number. If you wish to change the sequence after creating pins, please use the Edit screen and just drag and drop the items you wish to move. Please also note the point about implied places as mentioned in 1.) above. 1.5. Finding named places After you have made the initial record of the textual information, the application asks you to choose if the place is Real Real under a fictitious name (for example, Dorchester is called Casterbridge by Thomas Hardy) Fictitious, but either exactly or approximately locatable. If the place is Real you are given the option to search our gazetteer and chose the named place. This process works for all major places of habitation, and even some named buildings, but if it does not then please find the real place by using one of the following tips, or using the procedure outlined in 1.6 below: A. Tips for finding Digital Latitude and Longitude for places using Google Maps: Go to http://www.maps.google.com Enter the address you wish to pin. For example, “39 Wish Street, Southsea, Portsmouth.” Click to search. Page 3 of 6 How to work with Mapping Writing Right click on the balloon marker Click “What’s here” and the Latitude and Longitude appear in the search box above the map, in the form 50.787489,-1.078123 (Lat first, Long second). Note that if the place is not found, the balloon will change in its appearance – round if a near match, yellow if not a match. Sometimes finding old place names needs a little diligence. Google will often come up with a helpful suggestion if the spelling has changed. [Note that places west of Greenwich or south of the equator are prefaced with a minus sign.] B: Tips for Wikipedia If found in Wikipedia, you will usually see that the geographical co-ordinates are given in the degrees and minutes in the right-margin. If you click on these co-ordinates, you will be taken to the Geo-Hack server which will give you the digital values. For example, Jefferson’s house at Monticello in Virginia is 38.010281, -78.4523. 1.6 Adding a new named and real place to the gazetteer, and finetuning the co-ordinates You can add a new real place to our gazetteer by using the “manually add coordinates” option. If you use the procedure in 1.5 to find the place, then all you need to do is enter the digital latitude and longitude. The application will then show you a map pin which you can move hither and thither until you have exactly the right place. Click to save this data. Note it is possible to use Google maps to help fine-tune the location of a particular building or spot: go to maps.google.com and enter the latitude (N or S of equator) and then the longitude (E or W of Greenwich) in the search box (for example, “51.478,0.002” will give you the Greenwich meridian as it passes through the Greenwich observatory. Use minus signs to indicate east of Greenwich or south of the equator. Once you are happy with the data, copy into Mapping Writing. 1.7. Adding a new fictitious named place. Where a text uses fictitious names, it may be possible to locate them precisely (E.g. Hardy uses Casterbridge for Dorchester; George Eliot’s “Middlemarch” is generally agreed to be Coventry) or approximately by guess work (e.g. places mentioned as near Middlemarch). Page 4 of 6 How to work with Mapping Writing 2. Kinds of Displays 2.1. Primary Display The primary display shows all the places mentioned in the text showing their numerical sequence. 2.2 Journeys or Narratives Journeys and narratives are two kinds of chronology which may exist within a text. The distinction between a journey and a narrative is not hard-and-fast since all journeys in a textual representation are also narratives. The intended distinction is between representations which are primarily focused on travel, and representations which happen to include travel (i.e. where the travel aspect is incidental to the narrative). In the former, the narrative will be entirely governed by the sequence of places visited. The Adventures of Robinson Crusoe provides a good example of journeys, since the work is composed of Crusoe’s relation of eight distinct journeys. Daniel Deronda provides a good example of a work where narratives are to the fore since Eliot’s novel begins in a casino in Neubronn, Germany, where Deronda first sees Gwendolen Harleth. Over the next several hundred pages the novel will narrate how both characters came to be there. In neither narrative is the journey of other than incidental interest, although the fact that they go there is. Similarly, one might consider Elizabeth Bennett’s journey to Darcy’s home at “Pemberley” in Derbyshire where the place and their meeting is significant but the route taken to get there is not. To map journeys and narratives, use the chronology option to create a narrative, then allocate to it the map pins which have already been added to the Primary Display. Please also note the point about implied places as mentioned in 1.) above. Page 5 of 6 How to work with Mapping Writing Specimen Table Format Place DATE begins Format: Yyyy-mmdd Short Headline for pin Quotation Page Comme no. nt (if any) [delete this and the next row which are provided by way of example] 1632 Birth of Crusoe I was born in the year 1632, in the city of York, of a good family, though not of that country, my father being a foreigner of Bremen, who settled first at Hull. He got a good estate by merchandise, and leaving off his trade, lived afterwards at York, from whence he had married my mother, whose relations were named Robinson, a very good family in that country, and from whom I was called Robinson Kreutznaer; but, by the usual corruption of words in England, we are now called - nay we call ourselves and write our name - Crusoe; and so my companions always called me. 3 York Page 6 of 6