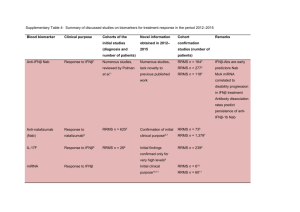

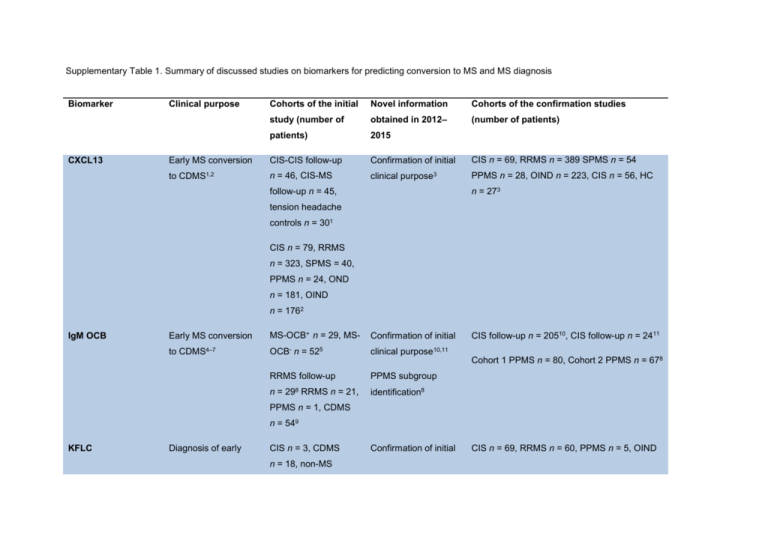

Supplementary Table 1. Summary of discussed studies on

advertisement

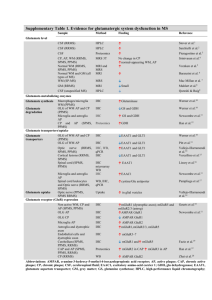

Supplementary Table 1. Summary of discussed studies on biomarkers for predicting conversion to MS and MS diagnosis Biomarker CXCL13 Cohorts of the initial Novel information Cohorts of the confirmation studies study (number of obtained in 2012– (number of patients) patients) 2015 Early MS conversion CIS-CIS follow-up Confirmation of initial CIS n = 69, RRMS n = 389 SPMS n = 54 to CDMS1,2 n = 46, CIS-MS clinical purpose3 PPMS n = 28, OIND n = 223, CIS n = 56, HC Clinical purpose n = 273 follow-up n = 45, tension headache controls n = 301 CIS n = 79, RRMS n = 323, SPMS = 40, PPMS n = 24, OND n = 181, OIND n = 1762 IgM OCB Early MS conversion MS-OCB+ n = 29, MS- Confirmation of initial to CDMS4–7 OCB- n = 525 clinical purpose10,11 CIS follow-up n = 20510, CIS follow-up n = 2411 Cohort 1 PPMS n = 80, Cohort 2 PPMS n = 678 RRMS follow-up n= 298 RRMS n = 21, PPMS subgroup identification8 PPMS n = 1, CDMS n = 549 KFLC Diagnosis of early CIS n = 3, CDMS n = 18, non-MS Confirmation of initial CIS n = 69, RRMS n = 60, PPMS n = 5, OIND MS12–14 neurological diseases clinical purpose15,17 n = 8915 n = 3715 CIS-CIS follow-up n = 38, CIS-MS follow-up CIS-MS n = 15, MS n = 39, OIND n = 77, viral/bacterial infections n = 33, OIND n = 8 n = 2017 OND n = 3316 CIS-MS n = 29, MS n = 70, non-CNS control n = 45, OIND n = 7817 MRZ reaction Diagnosis and MS n = 42, NMO prognosis of early n = 209 CIS-CIS MS9,18,19 n = 40, CIS-MS Confirmation of initial MS n = 47, siblings OCB+ n = 9, siblings OCB- clinical purpose20–22 n = 37 HC n = 5020 CIS n = 7 RRMS n = 6121 non-CNS-autoimmune neurological disorders n = 4918 n = 37, OIND n = 16, RRMS n = 26, SPMS n = 12, PPMS n = 822 MS n = 42, paraneoplastic neurological disorder n = 3419 CHI3L1 Early MS conversion to CDMS23–25 CIS-CIS n = 30, CISMS n = 3024 Confirmation of initial clinical purpose26–28 RRMS n = 156, SPMS n = 30, PPMS n = 66, HC n = 5726 cohort 1 RRMS n = 21, control n = 21, cohort 2 RRMS n = 21, control n = 21, RRMS n = 24, SPMS n = 24, NMO n = 12, Progression29 cohort 3 CIS n = 40, RRMS n = 38, progressive MS n = 16, control n = 2928 OIND n = 24, HC n = 2423 CIS follow up n = 8627 CIS = 109, RRMS n = 19229 MS n = 0, Alzheimer disease n = 10, ALS n = 10, stroke n = 10, HC n = 1925 NfL Diagnosis and RRMS n = 5, prognosis for early Alzheimer diseases MS30,31 n = 5, ALS n = 5, Confirmation of initial clinical purpose32–35 CIS-CIS n = 23, CIS-MS n = 19, CDMS n = 23 OND/HC n = 3,267 CIS-CIS n = 98, CIS-MS n = 10035 vascular dementia n = 531 CIS n = 67, OND n = 1834 CIS n = 38, RRMS CIS n = 62, RRMS n = 38, SPMS n = 25, n = 42, SPMS n = 28, PPMS n = 23, controls n = 7232 PPMS n = 6, nonCNS controls n = 28, OND n = 18, OIND n = 3930 miRNA-20a-5p Diagnosis of early RRMS n = 24, SPMS Confirmation of initial MS36 n = 17, PPMS n = 18, clinical purpose37 CIS n = 25, RRMS n = 25, HC n = 5037 HC n = 3736 miRNA-22-5p *Anti-KIR4.1 Diagnosis of early CIS n = 25, RRMS Confirmation of initial CIS n = 25, RRMS n = 25, HC n = 5037 MS MS37 n = 25, HC n = 5037 clinical purpose37,38 n = 4, HC n = 438 . . Diagnosis of a subset cohort 1: CIS n = 44, RRMS n = 49, SPMS of early MS39–41 n = 19, PPMS n = 10, OND n = 77, HC n = 14 . . . Differential diagnosis Cohort 2: CIS n = 53, RRMS n = 91, SPMS MS-NMO40 n = 1, PPMS n = 1, OND n = 130 HC n = 8 Cohort 3 CIS n = 49, RRMS n = 77, OND n = 12839 MS n = 286, HC n = 99, OND n = 10941 MS n = 268, OND n = 46, HC n = 4540 Blue background indicates a CSF biomarker, purple indicates a CSF+blood biomarker, and red indicates a blood biomarker. *) Inconclusive results Abbreviations: ALS; amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Anti KIR4.1 Anti-glial inward rectifying potassium channel 4.1, CDMS; clinical definite multiple sclerosis , CHI3L1, chitinase-3-like protein 1, CIS; clinical isolated syndrome, CNS; central nervous system, CSF; cerebrospinal fluid, CXCL13, CXC motif chemokine 13, HC; healthy controls, IgG, immunoglobulin G, IgM; immunoglobulin M, KFLC, kappa free light chains, miRNA, micro RNA, MRZ, measles, rubella, zoster, MS; multiple sclerosis, NfL; neurofilament light chain; NMO; neuromyelitis optica, OCBs; oligoclonal bands, OIND; other inflammatory neurological diseases OND; other neurological diseases, PPMS; primary progressive multiple sclerosis , RRMS; relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis, SPMS; secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. 1. Brettschneider, J. et al. The chemokine CXCL13 is a prognostic marker in clinically isolated syndrome (CIS). PLoS.One. 5, e11986 (2010). 2. Khademi, M. et al. Cerebrospinal fluid CXCL13 in multiple sclerosis: a suggestive prognostic marker for the disease course. Mult.Scler. 17, 335–343 3. Khademi, M. et al. Intense inflammation and nerve damage in early multiple sclerosis subsides at older age: a reflection by cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers. PLoS One 8, e63172 (2013). 4. Villar, L. M. et al. Intrathecal IgM synthesis predicts the onset of new relapses and a worse disease course in MS. Neurology 59, 555–559 (2002). 5. Villar, L. M. et al. Intrathecal IgM synthesis is a prognostic factor in multiple sclerosis. Ann. Neurol. 53, 222–226 (2003). 6. Villar, L. M. Influence of oligoclonal IgM specificity in multiple. 183–187 (2008). 7. Villar, L. M. et al. Intrathecal synthesis of oligoclonal IgM against myelin lipids predicts an aggressive disease course in MS. J. Clin. Invest. 115, 187– 194 (2005). 8. Villar, L. M. et al. Immunoglobulin M oligoclonal bands: biomarker of targetable inflammation in primary progressive multiple sclerosis. Ann. Neurol. 76, 231–40 (2014). 9. Brettschneider, J. et al. IgG antibodies against measles, rubella, and varicella zoster virus predict conversion to multiple sclerosis in clinically isolated syndrome. PLoS One 4, e7638 (2009). 10. Ferraro, D. et al. Cerebrospinal fluid oligoclonal IgM bands predict early conversion to clinically definite multiple sclerosis in patients with clinically isolated syndrome. J. Neuroimmunol. 257, 76–81 (2013). 11. Magraner, M. J. et al. Brain atrophy and lesion load are related to CSF lipid-specific IgM oligoclonal bands in clinically isolated syndromes. Neuroradiology 54, 5–12 (2012). 12. Desplat-Jégo, S. et al. Quantification of immunoglobulin free light chains in cerebrospinal fluid by nephelometry. J. Clin. Immunol. 25, 338–345 (2005). 13. Kaplan, B., Aizenbud, B. M., Golderman, S., Yaskariev, R. & Sela, B. A. Free light chain monomers in the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis. J. Neuroimmunol. 229, 263–271 (2010). 14. Presslauer, S., Milosavljevic, D., Brücke, T., Bayer, P. & Hübl, W. Elevated levels of kappa free light chains in CSF support the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis. J. Neurol. 255, 1508–1514 (2008). 15. Senel, M. et al. Cerebrospinal fluid immunoglobulin kappa light chain in clinically isolated syndrome and multiple sclerosis. PLoS One 9, e88680 (2014). 16. Goffette, S., Schluep, M., Henry, H., Duprez, T. & Sindic, C. J. M. Detection of oligoclonal free kappa chains in the absence of oligoclonal IgG in the CSF of patients with suspected multiple sclerosis. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 75, 308–310 (2004). 17. Presslauer, S. et al. Kappa free light chains: diagnostic and prognostic relevance in MS and CIS. PLoS One 9, e89945 (2014). 18. Jarius, S. et al. The intrathecal, polyspecific antiviral immune response: Specific for MS or a general marker of CNS autoimmunity? J. Neurol. Sci. 280, 98–100 (2009). 19. Jarius, S. et al. Polyspecific, antiviral immune response distinguishes multiple sclerosis and neuromyelitis optica. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 79, 1134–1136 (2008). 20. Persson, L. et al. Elevated antibody reactivity to measles virus NCORE protein among patients with multiple sclerosis and their healthy siblings with intrathecal oligoclonal immunoglobulin G production. J. Clin. Virol. 61, 107–112 (2014). 21. Rosche, B. et al. Measles IgG antibody index correlates with T2 lesion load on MRI in patients with early multiple sclerosis. PLoS One 7, 1–4 (2012). 22. Brecht, I. et al. Intrathecal, polyspecific antiviral immune response in oligoclonal band negative multiple sclerosis. PLoS One 7, 1–5 (2012). 23. Correale, J. & Fiol, M. Chitinase effects on immune cell response in neuromyelitis optica and multiple sclerosis. Mult.Scler. 17, 521–531 24. Bonneh-Barkay, D., Wang, G., Starkey, A., Hamilton, R. L. & Wiley, C. a. In vivo CHI3L1 (YKL-40) expression in astrocytes in acute and chronic neurological diseases. J. Neuroinflammation 7, 34 (2010). 25. Comabella, M. et al. Cerebrospinal fluid chitinase 3-like 1 levels are associated with conversion to multiple sclerosis. Brain 133, 1082–93 (2010). 26. Canto, E. et al. Chitinase 3-like 1: prognostic biomarker in clinically isolated syndromes. Brain (2015). doi:10.1093/brain/awv017 27. Modvig, S. et al. Cerebrospinal fluid levels of chitinase 3-like 1 and neurofilament light chain predict multiple sclerosis development and disability after optic neuritis. Mult. Scler. J. 1–10 (2015). doi:10.1177/1352458515574148 28. Hinsinger, G. et al. Chitinase 3-like proteins as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers of multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. (2015). doi:10.1177/1352458514561906 29. Martínez, M. A. M. et al. Glial and neuronal markers in cerebrospinal fluid predict progression in multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. (2015). doi:10.1177/1352458514549397 30. Norgren, N., Rosengren, L. & Stigbrand, T. Elevated neurofilament levels in neurological diseases. Brain Res. 987, 25–31 (2003). 31. Teunissen, C. E. et al. Combination of CSF N-acetylaspartate and neurofilaments in multiple sclerosis. Neurology 72, 1322–1329 (2009). 32. Disanto, G. et al. Serum neurofilament light chain levels are increased in patients with a clinically isolated syndrome. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 1–4 (2015). doi:10.1136/jnnp-2014-309690 33. Fialová, L. et al. Serum and cerebrospinal fluid light neurofilaments and antibodies against them in clinically isolated syndrome and multiple sclerosis. J. Neuroimmunol. 262, 113–20 (2013). 34. Khalil, M. et al. CSF neurofilament and N-acetylaspartate related brain changes in clinically isolated syndrome. Mult. Scler. 19, 436–42 (2013). 35. Kuhle, J. et al. A comparative study of CSF neurofilament light and heavy chain protein in MS. Mult. Scler. 19, 1597–603 (2013). 36. Cox, M. B. et al. MicroRNAs miR-17 and miR-20a inhibit T cell activation genes and are under-expressed in MS whole blood. PLoS.One. 5, e12132– (2010). 37. Keller, A. et al. Comprehensive analysis of microRNA profiles in multiple sclerosis including next-generation sequencing. Mult. Scler. 20, 295–303 (2014). 38. Siegel, S. R., Mackenzie, J., Chaplin, G., Jablonski, N. G. & Griffiths, L. Circulating microRNAs involved in multiple sclerosis. Mol. Biol. Rep. 39, 6219–25 (2012). 39. Srivastava, R. et al. Potassium Channel KIR4.1 as an Immune Target in Multiple Sclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 367, 115–123 (2012). 40. Brill, L. et al. Increased anti-KIR4.1 antibodies in multiple sclerosis: Could it be a marker of disease relapse? Mult. Scler. J. 4, 1–8 (2014). 41. Nerrant, E. et al. Lack of confirmation of anti-inward rectifying potassium channel 4.1 antibodies as reliable markers of multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. 1352458514531086– (2014). doi:10.1177/1352458514531086