EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

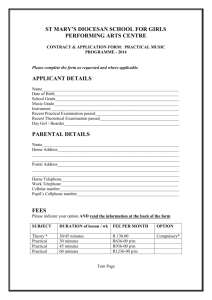

advertisement