Ackroyd uses these different kinds of illicit and uneasy text

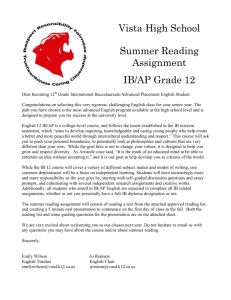

advertisement