chemists aromatic

advertisement

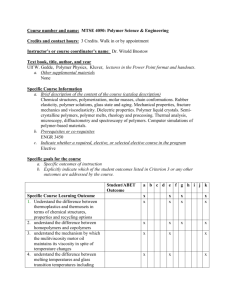

C151-A7 Kevlar, the “Not-so-Secretive” Bullet Proof Fiber Figure 1: Left, golden yellow Kevlar aramid fiber. The diameter of the filaments is about 10 μm. [1] , right Kevlar, molecular structure While Kevlar is found in ordinary bicycle tires and tennis rackets – to places where it is least expected like windsurfing sails, the back-plate on your smartphone, or the material on your favorite HyperDunk or Zoom Kobe VII shoes – this outstanding molecule’s properties allow it to be used in more appropriate scenarios. Kevlar is more commonly known for its properties that allow bullet-proof vests to be bullet proof. In fact, because of its fantastic properties that allow it to be “almost” impenetrable by a bullet, it is often used in U.S. Navy submarine underwater cables for noise-capacity. It is clear that this polymer/fiber is “super-tough.” Now, one might ask “well how is Kevlar impervious to a bullet compared to other polymers?” The answer is in the chemistry: the basic structure and properties of this large molecule, as well as its inter-molecular bonds and interactions. The IUPAC name of Kevlar is poly-paraphenylene terephthalamide (Figure 1, right). It is a specially blended para-aramid synthetic fiber, was first synthesized and developed by PolishAmerican chemist, Stephanie Kwolek in 1965. It soon became the trademark of the chemical company where Kwolek worked called DuPont. In anticipation of the gasoline shortage of the 1970's and the need for more fuel-efficient cars, the DuPont research group led by Kwolek started a search for a new strong, but lightweight fiber to use for car tires. The discovery of Kevlar was unintentional. While trying dissolving one of her polymers, Kwolek noticed something different about the solution. During that time period, synthetic chemists would compare polymer solutions via the consistency and viscosity resembling molasses, and the clear color like pure distilled water. Kwolek studied this material, and noticed that it had a similar viscosity like water. Moreover, Kwolek’s sample of this polymer solution was fibrous and cloudy. Ordinarily, such a cloudy, opalescent, and low viscosity solution would be discarded. However, Kwolek decided to keep her solution for further testing after some convincing from her technician, Charles Smullen. This new fiber was tested in a machine called the spinneret. This was designed to test the durability of fibers. Both Kwolek and Smullen were amazed to find that it did not break, unlike other well-known fibers at the time (i.e. nylon, etc.). After her discovery was made known to her superiors, the significance was quickly realized and Kevlar was born. This sparked a new field of polymer chemistry that had not previously been explored. After six years, DuPont was able to commercially produce Kevlar, reaching the market in 1971. Figure 2: Chemist Stephanie Kwolek, the inventor of Kevlar. [3] Kevlar’s unique chemical structure and long chain molecule arrangement allows it to make an ultra-tight fiber that when woven into a sheet, is able to stop a speeding bullet. Not only is Kevlar is super strong, but also very light despite it being five times the strength of steel on an equal-weight basis. Unlike most plastics, it can withstand temperatures well above 850°F. It can be ignited, but is easily extinguished if the heat source is removed. Additionally, Kevlar is capable of remaining soft and pliable down to -320°F and is even slightly stronger at lower temperatures, which makes it perfect for Arctic conditions. It is able to remain virtually unchanged after exposure to hot water for more than 200 days and its properties are virtually unaffected by moisture. Kevlar is a synthetic polymer. Much like, nylon, Teflon, and polyester, it is made in lab rather than by nature. In synthesis, a single Kevlar polymer chain could have anywhere from five to a million monomers bonded together. Each Kevlar monomer contains 14 carbon atoms, 2 nitrogen atoms, 2 oxygen atoms, and 10 hydrogen atoms. Its molecular formula is [-CO-C6H4CO-NH-C6H4-NH-]n and as described before, is a type of fiber called an aramid, which is short for what is known as an aromatic polyamide. These molecules form long, highly-oriented chains. The fibers can be spun into mats or fabrics to exploit their special properties. It is made by a condensation reaction of an amine (1,4-phenylene-diamine) and acid chloride (terephthaloyl chloride), yielding hydrochloric acid as a byproduct. The solvent originally used for this polymerization was Hexamethylphosphoramide (HMPA). Due to safety reasons, that HMPA is extremely toxic and a really carcinogenic base, DuPont replaced it with a solution of N-methyl-pyrrolidone and calcium chloride. Notably, the production of Kevlar isn't the most feasible, due to the difficulties that arise from using concentrated sulfuric acid, which is needed to keep the water-insoluble polymer in solution during its synthesis and spinning processes. This includes time, costs, and labor for companies that make Kevlar. Figure 3: Chemical synthesis of Kevlar from 1,4-phenyl-diamine (para-phenylenediamine) and terephthaloyl chloride. [1] Despite the difficulties in the synthesis, the end product is worthwhile by its extreme durability. The polymer, itself, contains many components that contribute to its overwhelming strength. Looking at Figure 1 and Figure 3, the molecular structure of Kevlar includes a unique polyaromatic amide (i.e. aromatic and amide functional groups). Other polymers with a high breaking strength often have one or both of these molecular groups in common. When the molten Kevlar is spun into fibers, the polymers have a crystalline arrangement. The polymer chains are oriented parallel to the fiber's axis. This orderly arrangement of molecules, known as a crystalline structure, is what contributes significantly to Kevlar's unique strength and rigidity. The structure of Kevlar chains, consisting of these relatively rigid molecules, tends to form mostly planar sheets. Figure 4: Ball and stick model of a single layer of the Kevlar crystal structure. [1] This is due to the para-orientation of the benzene rings. The high strength of the Kevlar polymer comes from the many inter-chain bonds. When Kevlar is spun, the amide groups are able to form hydrogen bonds between the polymer chains. This acts like glue holding the separate polymer chains together, resulting in the formation of a sheet that has a very high tensile strength of about 3,620 MPa and a relative density of 1.44. Figure 5: Molecular representation of the polymer in space. The bold represents a single monomer unit and the dashed lines indicate hydrogen bonds. [1] Additional strength also comes from the aromatic stacking interactions between adjacent strands. The presence of aromatic compounds in Kevlar has pushed chemists to research about the correlation between the aromatic compounds and Kevlar's strength. The challenge was finding out how exactly these aromatic groups were oriented within a fiber of Kevlar. Using synchrotron light, it became possible to detect the presence of different groups of atoms by utilizing the selective absorption of light. Scientists were able to uncover the orientation of the molecules in materials by using a special type of x-ray microscopy called XANES. The images produced were able to show that the aromatic components of Kevlar had a radial orientation, much like spokes on a wheel. Because the sheets can stack in radial fashion, it allows for additional interactions between the face-to-face aromatic groups on neighboring sheets. This radial orientation is imperative because it allows the polymer chains to be highly-ordered and symmetric, just like the atoms in a crystal. The well-ordered structure of a fiber of Kevlar gives it virtually no room for any flaws or weak places. This is quite possibly the biggest reason for the exceptional strength of Kevlar and is what gives it the upper hand against other fibers. Figure 6: The most recent XANES images confirm that the aromatic components of Kevlar have a radial (spoke-like) orientation, giving it a high degree of symmetry and order. [2] The downsides of Kevlar are that, like other plastics, long exposure to ultraviolet light can cause discoloration and some degradation of the fibers. Also, although it can resist attacks from many different chemicals, long exposure to certain strong acids or bases can degrade it over a period of time. Overall, it still makes for a great polymer despite its longevity. Because of its chemistry, the applications of Kevlar are endless. The most well-known application is the bullet-proof, tactical vests that the law enforcement officers wear. This makes Kevlar a molecule that changed the world because it has been responsible for saving thousands of lives. It has changed the way police officers approach their work. It offers them a higher sense of security and protection. Since they never know what type of weapons or danger that they may be up against, this body armor made with 100% Kevlar fiber can easily mean the difference between being able to walk away from a criminal assault and being fatally injured at the scene. Research has consistently shown that wearing personal body armor reduces the chance of bodily injury or death caused by ballistic, stab, and slash attacks. The Kevlar vests work by catching a bullet in a multilayer web of woven fabrics. The different layers in the weave offer different functions. Kevlar based protective gear are also a favorite because it is considerably lighter and thinner than equivalent gear made of more traditional materials. Because Kevlar is also not only bullet proof, but extremely durable other applications also include ropes and cables used for land, sea, and space. The Kevlar harnesses the strength, temperature resistance, flexibility, and lightness that manufacturers need. Some examples are mountaineering ropes, fishing lines, electro-mechanical cables, and fine gauge cables, which are used for electronic device applications such as mobile phone cables, computer power cords, USB cords, and MP3 earphone cables. Its application in the fine gauge cable industry is superior because it provides excellent robustness, fatigue resistance, shrinkage, and durability for its products. The fiber’s resistance to chemicals and extreme temperature also makes it an ideal component for ropes and cables that are used under severe loads in harsh environments. Anywhere from the bottom of the ocean to the surface of Mars, Kevlar can be found. In seawater, Kevlar ropes are up to 95% lighter than steel ropes of comparable strength. The lightweight rope constructions made with Kevlar fiber help enable rescue teams to handle and deploy equipment far more easily, often saving valuable seconds. In space travel, Kevlar fibers have been proven strong enough to withstand the extreme forces and temperature fluctuations. It is used in the space shuttle to help protect against impacts from orbital debris. And when the Mars Pathfinder landed on the surface of Mars, Kevlar ropes helped to secure the inflated landing cushions, which were reinforced with Kevlar fibers themselves. This allowed it to complete its 40 million mile journey fully intact and ready to explore Mars. Although the use of Kevlar in Mars is not entirely relevant to our everyday lives, it still serves as an example of how a simple polymer accidently made in a lab over 40 years ago can go on to make revolutionary changes in today's world. The applications of Kevlar continue to expand. New challenges are being embraced and scientists are continuously innovating to make the world a better place with Kevlar. From the humble beginnings of its discovery, to the overthe-moon applications we see today, it's safe to say that the journey of poly-paraphenylene terephthalamide is nothing less. Bibliography: 1. "Kevlar." Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, 02 Mar. 2014. Web. 07 Feb. 2014. 2. "Kelvar-The Wonder Material." LBNL -KEVLAR. Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, n.d. Web. 07 Feb. 2014. 3. May, Paul. "Kevlar." The Molecule of the Month. University of Bristol, n.d. Web. 07 Feb. 2014.