File

advertisement

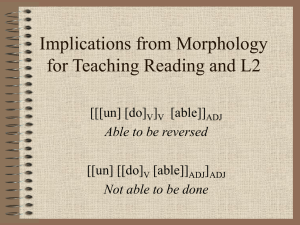

Erin Slightom Paper/Project FL663 Dr Abreu December 14, 2012 A second language curriculum is rich with topics. Instructors are tasked with imparting an entire language to beginning students. Beginning a new language study is so much more than learning new words, students must begin to look at all aspects of language, lexicon, syntax, semantics, and morphology. It is a long road to proficiency. Being proficient is a variable standard depending on the expectations of the classroom and the students’ desired outcome. Students’ desired outcome communicative ability in the L2. While students goals may vary they are all held accountable to learning all parts of the language. One of the most problematic components of L2 study is inflectional morphology. The inflectional morphology of language creates a stumbling block for L2 learners no matter what that language may be. This paper discusses two opposing theories of language acquisition and how that impacts inflectional morphology accuracy for L2 students. As well as how students in different language learning settings affect the accuracy of inflectional morphology. Inflectional Morphology Morphology is defined in “An Introduction to Language as The study of the structure of words; the component of the grammar that includes the rules of word formation” (Fromkin, Rodman & Hyams, 2011). Morphology is the altering of a root word by adding affixes. Different languages use morphology in different ways. A few examples of morphology in English include taking the verb believe, by adding the suffix –able makes it the adverb believable. Verb tense can be changed with the suffix –ed, talked makes the verb past tense. Prefixes can make adjectives opposite, the word behave becomes the opposite with the prefix mis- misbehave. Spanish is an example of a morphologically rich language. It requires morphology in more areas than English, most notably in noun adjective agreement and subject verb agreement . Differently from English, Spanish has a rich morphology in its verb structure allowing the suffix of a verb to indicate person and tense. (Herschensohn, Stevenson, & Waltmunson, 2005) The affix is so distinct in Spanish verbs that it is a null subject language, permitting the omission of the subject pronoun. Other languages cannot be null subject because the affixes for verbs don’t change based on the subject and verb. For example in English most irregular verbs only have a suffix of –s for third person singular. Spanish has a different suffix for all possible subjects; both singular and plural of the first, second, and third person (Herschensohn, Stevenson, & Waltmunson, 2005). The subject is identified easily without it being explicitly stated or written. Spanish verbs have the ability to provide so much information simply by the affixes. Native language learners master their languages easily. A study conducted by Herschensohn et al reveals the native language morphology use is quickly mastered by young children in their native language, showing that children of ages ranging from 1 year 7 months to 4 year 7 months demonstrated 97% accuracy in production of verbal morphology (Herschensohn, Stevenson, & Waltmunson, 2005). This is not the case for students of a second language. Inflectional morphology is a stumbling block for L2 learners which persists for even highly proficient individuals, (Jiang, 2004) no matter what language they are learning. This common phenomenon has been studied extensively in SLA, producing different theories as to why L2 learners struggle to master this skill especially in spontaneous production. Theories Throughout the research of morphological accuracy among L2 learners there is mentioned the theory of Failed Functional Features Hypothesis presented by Roger Hawkins and Cecilia Yuet-hung Chan (Hawkins Chan1997). Their research found that L2 learners are impacted by the constraints of the Critical Period and employing Universal Grammar to achieve native-like accuracy. This theory concludes that L2 learners who begin learning after childhood use their “L1 syntax with L2 lexical items by mapping morphophonological forms from L2 on to L1 feature specifications” (Hawkins, Chan 1997). Indicating that students of L2 apply their lexical knowledge of L2 onto their syntactical knowledge of their L1 (Hawkins, Chan 1997). In addressing the abilities of long term L2 learners they are able to “progressively approximate in performance to native speakers and they will establish grammatical representations which diverge from those of native speakers, as well as from their own L1s, but which are nevertheless constrained by the principles of UG:‘possible grammars’ (Hawkins Chan 1997). The basis of this argument is that the Critical period impacts L2 learners from achieving native like accuracy. Critical period is the belief that students of an L2 will not be able to adopt native like accuracy and that morphology and syntax are co-dependent (Herschensohn et al) An opposing theory founded by Schwartz and Sprouse is the theory of Full Access/Full Transfer (FA/FT). This theory believes that the native language grammar; “Assumes transfer of native lexical and functional categories and values; L2 stages that develop from syntax to morphology; and development of syntax, that is not directly dependent on that of morphology, with error indicating a mapping problem in L2 morphological realization” (Herschensohn, Stevenson, & Waltmunson, 2005). The FT/FA theory states that students ‘failure to master accuracy in inflectional morphology is a shortfall in recognizing the phonetic realization of morphology. The Critical Period theory is discounted with L2A (second language acquisition) is the same for adult and children learners. (Herschensohn, Stevenson, & Waltmunson, 2005) Neither the FT/FA theory nor the FFFH can absolutely explain the performance, or lack of performance, for all L2 learners. The subsequent studies demonstrate that L2 learning is different for different students depending on the stage. The question of best application lies in the combination of implicit and explicit input. Application to L2 classroom Human beings learn their native language implicitly, with unconscious knowledge of language formation (Fromkin, Rodman & Hyams, 2011). Upon entering the academic setting of Primary school students are taught about their language, explicitly or conscious instruction of language knowledge. In the study “The mental representation and processing of Spanish verbal morphology” native language acquisition (Brovetto, Ullman, 2005), found that native speakers do not have an exclusive process for production of inflectional morphology; “a combination and interaction of two different systems are required to account for the representation and processing of Spanish verbal morphology” (Brovetto, Ullman, 2005). There is no absolute in how to teach inflectional morphology in an L2 classroom. The beginning student of Spanish is directed to notice inflectional morphology right away in the beginning level text books. For example the McDougal Little Level 1 text in the series Buen Viaje show verb charts with the different suffixes for verbs within the first 3 chapters, but it is also surrounded by examples of implicit learning. The application is trying to impact metalinguistic knowledge as well as implicit knowledge. The implicit knowledge calls on visual cues to access L1 abilities in learning L2. While the production performance of students may seem dismal there is proof that their comprehension of L2 far exceeds their production abilities. (Herschensohn et al) The study of early L2A students, by Herschensohn et al offers insight of how young L2 students behave compared to native speakers and traditional L2 students. These students were studied to see how their pre-puberty education affected their linguistic abilities in inflectional morphology. They were found to have morphological awareness, they used inflectional morphology in errors of commission, but there were still inaccuracies. The researchers sited the biggest impact on their language abilities was tied to input, and that was the path to morphology acquisition (Herschensohn, Stevenson, & Waltmunson, 2005). Jiang found in his study of highly proficient L2 leaners (Jiang, 2004) that explicit knowledge and automatic competence are not a given with people who have had years of language instructions, and living and working in a target language country. The study characterizes students who have many years of language study, use and competence as having continued inaccuracies in inflectional morphology (Jiang, 2004). While this study looks at the difference between competence and performance it is beneficial to note that even students with many years of input still struggle with inflectional morphology. Jiang summarizes the study as “ Skill-oriented constructs such as restructuring or automatization are obviously insufficient to explain the integration processes, as practice does not seem to make perfect in L2 inflectional morphology” (Jiang, 2004). While the FFFH states that “continued exposure (to L2) will progressively approximate performance to native speakers” (Hawkins, Chan, 1994). Heritage speakers offer another angle to study implicit versus explicit instruction. Heritage speakers are categorized by their exposure to language input from birth but then learning a different language once enrolled in school. Compared to students of L2 classroom (Montrul, 2011), heritage speakers have had a far greater exposure to implicit language knowledge while classroom learners are exposed more to explicit knowledge, therefore it would be expected that the FFFH would not apply to heritage speakers. . In study by Montrul (Montrul, 2011) we see that heritage speakers demonstrate inflectional verbal morphology accuracy in verbal production but not in written production (Montrul, 2011). Whereas the classroom students who would suffer from Critical Period (Montrul, 2011) are more capable in written inflectional morphology. The amount of input along with explicit language instruction may prove to be the best of both worlds. Even with early exposure to the concepts students can still demonstrate short falls in their production of accurate inflectional morphology. . For example in my own classroom my students can distinguish between tengo (yo) and tiene (él/ella/usted) when explicitly asked the difference between these verbs. In application, either oral production of written production, the same students who explicitly know the difference will use them inaccurately. In the study by Jiang, we see that L2 English speakers who lived and worked in the United States who were proficient enough to work in their L2 continue to present with inaccuracy and uncertainty with morphology. Jiang characterizes it as morphology insensitivity. (Jiang, 2004) ESL students compared with native English speakers While I consider myself to be a proficient speaker; able to converse freely with little to no hesitation as well as successfully communicating with native speakers, I am continually riddled with problems in morphological agreement. I am able to recognize inaccuracies the minute they leave my mouth, often times correcting it milliseconds after the inaccurate statement has been made, but I cannot be a morphologically error free speaker. Therefore as an instructor I must provide students with both implicit languages through input and explicit knowledge about the language. Implicit language input is successfully executed by providing students with real and authentic opportunities to experience the language. Besides classroom instructions focusing on common vocabulary that continually practices what the students have recently learned students must be exposed to real language that is actually used by Spanish speakers. Real language exposure in my community is rich with songs, magazines, children’s’ books, novellas, internet resources and movies. Students are asked to seek out what interests them and find it in Spanish, read and write about it. Explicit instruction calls the students to pay attention to the inflectional morphology that they encounter. Conscious language instruction calls on students to interpret the inflectional morphology of the verbs and explain why. This can be done with text book readings, lines of lyrics from songs, and even analysis of student writing. Beyond the traditional rote memory of verb conjugations students can find more practical application of this knowledge. In conclusions I feel that the expectations of the Second language classroom should reflect the realistic outcomes. Becoming accurate in production of inflectional morphology is not a realistic task for L2 students. While the goal should be to move towards accuracy it is not an attainable goal for students in a secondary setting. What is most important is to provide good input supported with metalinguistic knowledge. Works Cited Brovetto, C. Ullman, M.T. (2005). The mental representation and processing of Spanish verbal morphology. Selected Proceedings of the 7th Hispanic Linguistics Symposium, ed. David Eddington, 98-105. Clahsen, H. & Felser, C. (2006). Grammatical processing in language learners. Applied Psycholinguistics, 27, 3-42 Fromkin, V., Rodman, R., & Hyams, N. (2011). An introduction to language. (9th ed.). Boston, MA: Cengage Learning. Hawkins, R., & Chan, C. (1997). The partial availability of Universal Grammar in Second language acquisitions: The “failed functional features hypothesis.” Second Language Research, 13, 187-226. Herschensohn, J., Stevenson, J. & Waltmunson, J. (2005). Children’s acquisition of L2 Spanish morphosyntax in an immersion setting. International Review of Applied Linguistics, 43, 193-217 Jiang, N. (2004). Morphological insensitivity in second language processing. Applied Psycholinguistics, 25. 603-634 Montrul, S. (2011). Morphological errors in Spanish second language learners and heritage speakers. Studies in Second Language Acquisition,33, 163-192. Lardiere, D. (2004). On morphological competence. Proceedings of the 7th Generative Approaches to Second Language Acquisition Conference (GASLA 2004), ed. Laurent Dekydtspotter et al., 178-192. Sharwood Smith, M. (2004). In two minds about grammar on the interaction of linguistic and metalinguistic knowledge. Transactions of the Philological Society, 102;2, 255-280. Yan-kit Ingrid Leung. (2002). Proceedings of the 6th Generative Approaches to Second Language Acquisition Conference (GASLA 2002), ed. Juana M. Liceras et al., 199-207. Somerville, MA: Cascadilla Proceedings Project. Target Language- Spanish L2 learners SFLL: 1.2, 1.3, 4.1, 5.1 Goal- While reading a short passage of Spanish students will be able to identify the person and tense of verbs based on inflectional verb morphology. Then be able to edit their own writing by identifying the verbs’ inflectional morphology. Outline- This activity would be applicable to Spanish learners beyond second semester of Spanish 1. They will have a strong foundation in present tense verbal morphology being able to identify the person. This kind of activity can simply be applied to more advanced levels of learners requiring them to look for different tenses. For Spanish 1 explicit teaching is best with familiarity therefore I will use a passage they are familiar with. Victor is a character based off of Jim Wooldridge’s song Guapo. It is a man singing about how handsome he is and how that affects his life. It goes so far as having backup singers agreeing with his egotistical rant. The students learn the lyrics, learn the song and many of them sing a long, request the video and then proceed to include Victor in all of their open ended writings. This story was first introduced at the end of first semester, Spanish 1. Teacher Instructions- In preparation of this activity prime the students’ knowledge of inflectional morphology of verbs. Ask the students to verbally explain the difference between “tengo” and “tiene”. Ask students to explain what the inflectional morphology means for Spanish verbs with specific examples of a regular verb such as “hablar”. Students will have had enough exposure of these endings to tell that “-o” indicates first person singular, “-(a) s” indicates second person singular, and “-(a)” indicates third person singular. It will be important to remind them that Spanish speakers often times omit the subject markers of “yo, tú, él, and ella”. Continue with other examples for as long as needed. Once students have had enough examples to prime their memory instruct them to read the passage. Clarify any incomprehension’s. It is very important that students understand what they have read. They should have the opportunity to ask clarification questions. Once they understand what they have read have them go back and underline/highlight and number all the verbs. They will take the number for the verb, for example the first verb (#1); copy it on line numbered (1). Once they have copied the verb ask them to tell which person it is for. For the advanced classes recognizing tense have them also tell the tense. At this point in the school year students will have had lots of input and should be able to recognize the patterns in the verb morphology. Not all students will be as proficient but in general the average student will be able to see it. As this is an explicit application of recognizing inflectional morphology of verbs this is an opportunity to pay close attention to those students who haven’t mastered this skill. Student Instructions- You are going to read the following passage. 1. Make sure to ask questions of words and or phrases you aren’t familiar with. 2. Then go back and underline and number the verbs 3. Copy the verbs onto the lines with the corresponding number 4. Tell which person- yo (first person), tú (second person), él, ella (third person) the verb is inflected for. Evaluation- Student performance will be based on completion with careful reinforcement for inaccuracy. If it is totally inaccurate I would ask that student to come in during a free period for extra help. As inflectional morphology is not something easily mastered for production I want to reinforce it to students and make them aware of it? A realistic expectation of this kind of activity would be to have students accurately retell the events with some accuracy to inflectional morphology, specifically for the description of Victor. Follow-up activity Possible follow up activities include; 1. Have students the following day write a story about Victor, more advanced students may change the circumstances to make it more interesting/challenging. Once they have their own written activity students can then go back and edit the verbs for accuracy, comparing their work if need be. 2. For advanced students I would ask them to change the story to first person. Once they have written the activity have them go back and check the verbs for inflectional accuracy. 3. Take the same story, removing the verbs to create a cloze style activity. For advanced students leave the blanks with no suggestions and ask them to fill them in with verbs. For students who aren’t quite as advanced give them a choice of different verbs. Víctor el guapo Hay un muchacho egoísta. Él se llama Víctor. Víctor es alto y delgado. Tiene ojos verdes y pelo castaño. Víctor no es una persona buena. Él es egoísta. Él dice “Soy guapo, soy muy muy guapo”. Él quiere muchachas bonitas. Un día Víctor va (1) a la escuela. La escuela es (2) River City High School. La escuela tiene (3) un día especial. Es(4) el día de Homecoming. Víctor quiere bailar(5) con las muchachas. Quiere bailar (6) en el baile de Homecoming. Víctor dice (7) “yo voy a bailar (8) con todas las muchachas guapas en el baile.” En el baile hay (9)muchos estudiantes. Todos los estudiantes de River City High School quieren bailar (10) en el baile de Homecoming. Todos van a bailar (11)toda la noche en el baile. Víctor quiere bailar (12)con muchas muchachas. Víctor va (13)hacia una muchacha bonita. Victor le va a invitar (14)a bailar. La muchacha se llama (15)Rosalinda. Víctor le pregunta (16)--- ¿Quieres bailar (17) conmigo? Soy (18) muy guapo. Rosalinda le mira (19) a Víctor y le responde (20)--- ¡NO, no quiero bailar (21) contigo! Escribe el verbo 1. 2. Which person/thing the verb is inflected for Victor Translate the verb Goes River City High School Is 13. Va Es 14. 15. 5. 16. 6. 17. 7. 18. 8. 19. 9. 20. 10. 21. 11. 22. 12. Target Language – L2 Spanish learners, L1 English Goal- To apply inflectional morphology to verbs to change the perspective of an authentic piece of language Outline – Students will take a piece of language they are familiar with Te mando flores, Fonseca, to apply inflectional verbal morphology. Students in upper levels of Spanish learn this song in class over a week’s time. The students are tasked with listening to the lyrics and completing a cloze activity. The meaning of the lyrics are translated then applied to comprehension based activities. Familiarity with this song will make this more meaningful. Students would only be asked to do this activity for verbs which they have past tense inflectional familiarity. Teacher instructions- Once the students are familiar with the song Te mando flores and are comfortable with the meaning of the words ask them to change the lyrics to past tense by inflecting the verbs appropriately. The first thing to do would be to explicitly review the inflectional verb morphology for regular past tense verbs (-ar-é, -er/-ir –í, -car- que, estáestuvo, puedo- pude) and for those that will be affected in the song. This song is written in first person this allows a special review of those verbs which are considered “irregular” for 1st person past tense inflection. Also note the inflection change of stem changing verbs. Have students use the lyrics of the song. Take the verbs and rewrite them for the past tense. Student instructions- Imagine you wanted to apologize to you for a huge mistake and your love was too hurt to listen. Sing them this song to tell them how and why you are sending flowers. Using this familiar song take the present tense verbs written in the chart, 1. identify which person it is inflected for, 2. change them to the past. 3. Then translate the song Evaluation- This activity could be evaluated in two different ways 1. Accuracy- if the students are able to accurately inflect the verbs to the past tense. 2. Time- the amount of time it takes them to produce the past tense of inflected verbs. This again is an example of inflectional verb morphology practice. Students are not expected to have mastery of the verb morphology for written and oral production. Follow-up activities – 1. Students could use the lyrics to write/tell a story in the 1st person. 2. Students could use the lyrics as inspiration for writing a love story that involves someone sending flowers to another person. Some students may want to change it and do the opposite making the person who sends a less desirable item to end the relationship. 3. For more explicit practice part or all of the song could be inflected for a different person, for example 3 rd person instead of 1st person. 4. For a more challenging activity students could be asked to learn their lyrics and record themselves singing it to the original tune. 5. Students could be asked to make a video or slide show with the newly inflected verbs in place of the original. 6. For lower students a possibility is to have a quiz set up as a cloze activity asking the students to choose the correct inflection of the verb. Te mando flores que recojo en el camino y sentirte cerca de mi yo te las mando entre mis sueños quiero tenerte en mis brazos porque no puedo hablar contigo poder salir y abrazarte y te mando besos y nunca mas dejarte ir en mis canciones Quiero encontrarte en mis sueños y por las noches cuando duermo que me levantes a besos se juntan nuestros corazones ningun lugar está lejos Te vuelves aire para encontrarnos los dos si de noche hay luna llena dejame darte la mano si siento frio en la mañana para tenerte a mi lado tu recuerdo me calienta mi niña yo te prometo y tu sonrisa que seré siempre tu amor cuando despiertas no te vayas por favor mi niña linda yo te juro que cada dia te veo mas cerca y entre mis sueños dormido trato yo de hablar contigo Present tense Person Past tense Mando Recojo Puedo Duermo Juntan Vuelves Hay Siento Calienta Despiertas Juro Veo trato Está Prometo Ser