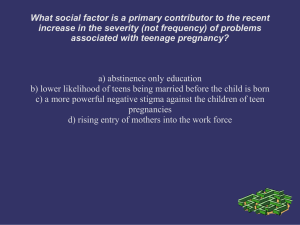

question 1

advertisement