CAN CHOREOGRAPHY REPLACE TEXT

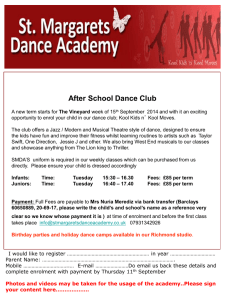

advertisement

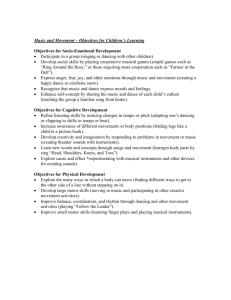

Ref: BA 2010-2011 Carly Main Can Choreography Replace Text? An Investigation into Dance being used as a progressive tool in Musical Theatre. This Independent Project is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for Module IPR6: Independent Project Supervisor: Victoria Stretton Trinity Laban 06/06/2011 Table of Contents Abstract……………………………………………………………………………………………… Page 3 Chapter 1: Overture………………………………………………………………………………. Page 4 Chapter 2: Fashions………………………………………………………………………………. Page 4 Chapter 3: Creatives……………………………………………………………………………… Page 6 Chapter 4: Limitless……………………………………………………………………………… Page 7 Chapter 5: Interpretations……………………………………………………………………… Page 8 Chapter 6: In Contrast…………………………………………………………………………… Page 9 Chapter 7: Finale………………………………………………………………………………….. Page 11 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………….... Pages 13-15 2 CAN CHOREOGRAPHY REPLACE TEXT? An Investigation into Dance being used as a progressive tool in Musical Theatre. Abstract Dance is a communicative device, and has been since long before the birth of human civilisation. Paintings from at least as far back as 3000 BC depict movement rituals. 1 Musical Theatre traces back to Ancient Greece, where the stage productions included music and movement. In the current Musical Theatre industry, though, dance is used scarcely to specifically communicate, and is more and more becoming a means of purely entertaining an audience. The focus of the following research is in the area of dance in Musical Theatre, and whether it can still be implemented as a progressive feature. The research approach adopted in this Independent Project includes relevant literature, online databases, consulting a cross section of people, and culminates in a practical performance alongside this dissertation which demonstrates my findings more academically. This project produced a number of findings, providing evidence that, currently, although there definitely is dance that advances the plot of Musical Theatre productions, this is not how movement is most commonly used in this context. My research showed that the peak time for dance to mean most lay with the role of director-choreographer, which is now an almost unheard-of role, and definitely does not exist in the West End of London. The conclusion I can draw from my studies is that, fortunately or unfortunately, although there are different scales and spectrums to measure how far a piece of dance can affect a narrative, ultimately it must boil down to opinion and personal preference. My research however argues for a return to the attitude of director-choreographer from the current choreographer – an attitude that uses dance thoughtfully and precisely, with knowledge behind the movement, to ensure that instead of receiving “audience approval… [One can] work for audience enlightenment.2 1 2 http://www.historyworld.net/wrldhis/PlainTextHistories.asp?historyid=ab82 Garebian, Keith. The Making of West Side Story. (Oxford; Mosaic Press, 1998), p16. 3 Overture Musical Theatre is defined as “a play or film whose action and dialogue is interspersed with singing and dancing”3. In other words, an art form that combines spoken word, song, music, and dance. The ratio of these different aspects however, can fluctuate greatly. My focus is going to be on the dance element of Musical Theatre. It is the discipline that can fall out of the equation and not affect whether the show still counts as “Musical Theatre”. Without music and songs, a musical becomes a play. Without acting, a musical becomes a concert. Without dance… a musical is still a musical. Choreography is as much of a creative outlet as singing and acting (“Choreographers are special people”4!), and it seems odd that this should be the case. Young professionals in Musical Theatre training have, customarily, more hours of dance than singing, acting, theory or voice – why should it be that after graduating, having spent this time on movement; it could be perfectly feasible that one never dances in a job? My aim for this Independent Project is to illustrate my experiments around my chosen title of ‘Can Choreography Replace Text?’ For the performance element I have taken backing accompaniments of songs from musicals that have a moving or meaningful lyric, and attempted to portray these lyrics through the medium of dance alone. I feel this should be something extremely plausible in the modern Musical Theatre world, but unfortunately is often overlooked. Fashions Through my research into various approaches to Musical Theatre dance, I have noticed that there are certain varying methods. I have been able to break down the styles of choreographed numbers in musicals in order to define five different fashions. There is the plot advancing type – in that without the sequence, the story would be missing something. Examples of this might be the opening, and in fact most of West Side Story – “what theatre historian Richard Kislan calls a breakthrough ‘movementconceived musical’”5, the dream ballet in Oklahoma! or ‘Angry Dance’ from Billy Elliot. There is the validating form – where the choreography is adding something to what 3 http://www.thefreedictionary.com/musical+theater Humphrey, Doris. The Art of Making Dances. (London; Dance Books Ltd, 1987), p26. 5 Garebian, The Making of West Side Story, p13. 4 4 has been said – like ‘Painting by Heart’ from Betty Blue Eyes, the races in Starlight Express, ‘Whipped into Shape’ from Legally Blonde or ‘Juggernaut’ from The Wild Party6. There is the accompanying approach – where the moves complement the music and lyrics – for example, most of the movement in Love Never Dies, ‘I’d Do Anything’ from Oliver!, the wedding waltz in Les Miserables, or ‘Something Better Than This’ from Sweet Charity. (Many “think that choreography is simply a matter of putting movement to music, which makes music the starting point. This incorrectly puts the onus on music to be the initiating agent whereas movement itself is the true core of dance.”7) There is the juxtaposition of choreography to songs, where the dance purposely goes against what has been said – for instance, Chicago, where a serene, beautiful number is performed whilst a hanging is referred to. And there is the unessential choreography – not necessarily a bad thing, but the moves mean nothing in terms of the show, the choreography could be put to any music of that tempo and have as much meaning as it does in its current context – dance for the sake of dance. Michael Bennett and Bob Avian, the partnership that were responsible for the choreography in Company, Follies, A Chorus Line and Dreamgirls (all Broadway) stated when being interviewed that they fought “like crazy against ever doing a dance that could be cut just because it is an extra beat in a musical… ‘okay, its time to bring the dancers on’…”8 Shows like 42nd Street 9, Crazy for You and The Rocky Horror Picture Show have contained this kind of choreography. “To paraphrase William Strunk, Jr.: a dance should have no unnecessary parts; this requires not that the choreographer make all his dances short nor that he avoid all detail, but that every movement tell (Strunk, Elements of Style, p17).”10 However, the most popular styles of dance to be incorporated into contemporary Musical Theatre shows seem to be the validating and accompanying sorts; perhaps these, along with the unessential style of creating dance, take least background and collaboration work. This is another valid 6 http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YERYu7toqMk&feature=fvst Blom, Lynne Anne and L. Tarin Chaplin. The Intimate Act of Choreography. (London; Dance Books Ltd, 1989), p161. 8 Mclee Grody, Svetlana and Dorothy Daniels Lister. Conversations with Choreographers. (Portsmouth; Heinemann, 1996), p97. 9 http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i5rCPKY-9zs 10 Blom and Chaplin, The Intimate Act of Choreography, p13. 7 5 point regarding Musical Theatre choreography – who has the final say in what should be essentially included? Creatives Roles of the creative team in any Musical Theatre production are often blended, blurred and combined in a variety of ways. If the musical direction interferes with any dramatic choices, the director can step in; if the choreography is hindering the vocal work, the musical director can step in; sometimes the director is also the choreographer; and so on. The choreographer can simply be the individual there to create steps to be performed to music –“the choreographer’s primary function is defining and supplying the specialized movement needs of the entire project”11 – but is this the way to go about making truly contemporary pieces of work? Or, instead, should the choreographer’s relationship with both the director and musical director (not to mention the lighting designer in the later stages) be an intimate one – to enable an absolute understanding of what is required from each dance number, in order to ensure the movement will progress the plot adequately. This only became a received notion after Oklahoma!, and even though that step was made, it is still more of a common phenomenon in current Musical Theatre for the choreography – and sometimes even the music – to have no relation to the show it features in, and be a straightforward aside. The role of Director-Choreographer was popular from the late 1950’s through to the 1980’s; with figures like Jerome Robbins, Gower Champion12, Bob Fosse and Tommy Tune13 taking the helm, many shows successfully made their debut – Fiddler on the Roof, Hello Dolly, 42nd Street, Sweet Charity, Pippin, Chicago, Best Little Whorehouse in Texas, Nine, and Grand Hotel14 in amongst far more, but as Musical Theatre continued to evolve, the position became often disbanded into two responsibilities once again, and now it is rarely seen. Look at the limited run shows that have recently been on in London (assuming limited run is defined as anything booking for less than a year). The 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Bee, showing at the Donmar Warehouse, contained 11 Berkson, Robert. Musical Theatre Choreography. (London; A&C Black, 1990), p6. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z0UoFogBFIU 13 http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZVE_sVcQaaM 14 http://www.musicals101.com/dancestage3.htm 12 6 movement that was not linked into the plot. The Umbrellas of Cherbourg, showing at the Gielgud, contained a mambo with balloons that meant nothing to the show as a whole. South Pacific is coming to the Barbican, and is fully expected to contain the nostalgic, ‘lovely’ dancing that harks back to when it was staged by Josh Logan in 1958. It will be extremely interesting to see the new adaptation of Crazy for You coming to Regent’s Park Open Air Theatre at the end of July, as the original production contained dance for dance’s sake15. When Stephen Mear (the choreographer on the production) did Sweet Charity, the moves were not related to the plot much at all; however Crazy For You has more scope for this concept than Sweet Charity did, and Mear’s past work shows that it is within his functioning as a choreographer to devise dance that is essential to a story – his co-choreographing on Mary Poppins, some of The Little Mermaid16 as well – and his work on the TV show So You Think You Can Dance (UK)17. His input to Shoes the Musical shows it to its greatest level – the choreography does not so much advance the plot as define it; Shoes not having a storyline as such, what the writers have done is mark up a history and insight into many different varieties of footwear. The dancers portray the personalities of shoes and of those who wear them, illustrate important events on the shoe timeline, evoke certain emotions regarding the wearing or purchasing specific types of shoes, and remind the audience of certain figures who were memorable in the shoe world. Mears and the five co-choreographers have done some genius work, and the dancing in the show is the absolute focus of it – the sun, around which the rest of the production rotates. Limitless Choreography is such an immensely intrusive, intuitive and interesting subject because there are less fixed factors to build from than with singing, or acting. “The choreographer is in a unique position. While the director has the existing dialogue to represent, the music director has the established score to reproduce… the choreographer is merely given an indication of the content which his work is to convey.”18 There is in fact an 15 http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YDJ6XFgze5M http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2DUXVAg7oWg 17 http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jfK6Wm4QoNw 18 Berkson, Musical Theatre Choreography, p12. 16 7 interminable aspect involved, from the very beginning. For the performer as well: singing has fixed lyrics, melody – bar riffs -, and techniques and emotions are changeable. Acting has a set script, and one would develop around the given circumstances and outside affecters to find character and depth. All a dancer has – and the choreographer must find the journey – is the set diameter of the stage on which he or she has to work (“the stage or arena that contains the dance has connotations all its own. There are certain places on the stage that are stronger, others that are intimate… theater people are acutely aware of the innuendoes of stage placement”19) and the music – although even that is sometimes removed from the equation as well – look at the Oz Dust Ballroom scene in Wicked. There is no limit to steps, shapes, and sequences when it comes to the world of Dance; there isn’t a fixed amount of moves, or a limit as to what one can do with their body. The possibilities are, literally, endless. It is therefore interesting that most Musical Theatre choreography sticks to such a traditional template. In the dance world people like Akram Khan, Daniel Linehan and the Rambert Company are creating innovative and original and thought provoking pieces of work; the evolution of dance is clearly noticeable and identifiable. With Musical Theatre, the landscape just seems so much smaller. Shoes showed a hint of the gravity that Musical Theatre choreography could carry – but the fact is that Shoes employed performers who were specifically highly skilled in dance, not triple threat performers, and the show played its run at Sadlers Wells – a venue known universally for putting on not Musical Theatre, but dance works. It even describes itself as “London’s dance house”20. Interpretation Everybody knows Agnes de Mille to have changed the face of Musical Theatre choreography forever with her work on Oklahoma!. She made American dance history.21 In the 1943 Broadway original by Rodgers and Hammerstein, directed by Rouben Mammoulian, de Mille – particularly in the dream ballet sequence – successfully integrated dance into the plot of the show22, which had never been done 19 Blom and Chaplin, The Intimate Act of Choreography, p52. http://www.sadlerswells.com/page/about-us 21 http://www.agnesdemilledances.com/biography.html 22 http://www.neh.gov/news/humanities/2004-09/robbins.html 20 8 up to that point. “The dream ballet… was not an interpolation or a special show-piece… It was an integral part of the action.”23 Jerome Robbins only took this further – having learnt from her as a performer in Oklahoma!; he would, according to Maya Dalinsky, “go on to make musicals where… the dancing moved the plot as much as the lyrics.” 24 This is the crux of what this project investigates. In a show like Robbins’ West Side Story, one could watch the choreography against the music, with no lyrics and no scenes, from start to finish, and still be able to accurately interpret the show: “…dance told much of the story, dance revealed character, dance incarnated the tragedy. And it did all this by breaking down the usual boundaries among song, drama, and movement.”25 At the other end of the spectrum, shows like Les Miserables and Into the Woods contain little to no movement whatsoever. This of course, is not necessarily to their detriment – clearly, as Les Miserables has passed the 25 year mark with flying colours (and remains my favourite show of all time despite its lack of dance). Richard Kislan writes that “dance symbols can be as effective as language or music symbols for dramatic communication. What sets dance apart is the universality in movement and gesture which is not bound like language to nationality or culture. Dance transcends geography in a way that language cannot. Dance humanizes expression in a way that music cannot.”26 This is genuinely what I believe, and why I feel so strongly about this project. “I see no reason against, and many for, an amalgamation of the spoken, sung or chanted word with movement.”27 I do not believe dance should replace lyrics and text in Musical Theatre – the performance part of this project is simply the biggest gesture I feel I can make: while I could have found instrumental numbers from shows, or even instrumental breaks between lyrics in Musical Theatre songs, and choreographed to this music, I felt that to remove lyrics and choreograph to a lyricised song would demonstrate my thesis more distinctly. In Contrast “The blunt fact of the matter is that subject matter is mostly of concern to the choreographer, and whether it takes the form of narrative, symbolism or a conviction about style, 23 Garebian, The Making of West Side Story, p15. http://www.neh.gov/news/humanities/2004-09/robbins.html 25 Garebian, The Making of West Side Story, p14. 26 Kislan, Richard. The Musical: A Look at American Musical Theater. (London; Applause Books, 1996.) 27 Humphrey, The Art of Making Dances, p125. 24 9 is of no importance; the enthusiasm for it and innate talent is what keeps it alive...”28 Despite my thesis, I also believe this statement to be partly true – although I don’t feel the message behind this is executed on West End stages, where for justifiable reasons the team are sometimes more wrapped up in the spectacle the audience must see (demonstrated by Wicked, which is sponsored by Universal). If the choreography has a plot advancing meaning behind it, even to the choreographer only, that has to be enough, because audiences interpret everything differently. I tested the dances I created for the practical segment of this essay on audiences who did not know the storylines of the songs (and sometimes the shows as well) that I was performing to, taking a cross section of 30 people. Five people were completely dispassionate towards Musical Theatre, five were less detached from it but could not describe themselves as regular theatre goers, five did describe themselves as exactly that, five had indirect links to Musical Theatre (whether it be a family member, part of their vocation), five were involved in Musical Theatre directly (as a vocation, be it the performance, creative or analytical side), and five were involved even more so in specifically dance (be it dance performance, choreography, or teaching). Although most were able to identify correctly what I was trying to say, some saw very different narratives emerging. For instance, the choreography I created to “I’ve Been” from Next to Normal, in my mind – and to most of my test audience, demonstrates the struggle of a husband and wife, the latter of who is struggling with bipolar. Using the open question ‘From watching this dance, what do you think the song is about?’ feeling that closed questions would be too leading - I had each test member write down what they thought the choreography depicted. Although 27 people were not able to specifically pick out bipolar, most at least could tell me one spouse was on medication, usually guessing they suffered from depression. However, one audience member determined a divorce. Not opposite ends of the spectrum at all, as in the number I make references to wedding rings and have a strong theme of removal and frustration, but not what I hoped to portray, as Dan still loves Diana unquestionably. This person was under the bracket of not having any affiliation with Musical Theatre, and so I do not take this as a defeat of any kind – the more you are involved with a 28 Humphrey, The Art of Making Dances, p27. 10 subject matter, the greater your understanding of that subject is bound to be. Although I made sure that Next to Normal was unknown to all 30 of them, the more of a link the test audience members had with Musical Theatre, the more accurate and elaborate their descriptions got, shown by receiving the analysis “husband and wife divorce” from one person uninvolved in Musical Theatre, watching or performing, and on the other hand having a dance student single out specific movements and analyse their separate meaning as well as their meaning in the piece – which is ideal, but fruitless to expect of a full audience watching a West End show. If I were to repeat this experiment, I would take a song with a less complex storyline, and attempt to choreograph for the non Musical Theatre goer, as I believe it is entirely possible for anybody to understand dance – but different categories of people, each with separate outside influences, will determine things somewhat differently. This is something a choreographer needs to think about when beginning a show – who is the market audience they are communicating to? Is this a show for families (shows like Shrek), teenagers and young adults (like Spring Awakening) or the slightly older (Betty Blue Eyes)? How commercial is the show; will it be something that only appeals to those involved in Musical Theatre already (shows by Jason Robert Brown or William Finn) or may somebody who has never set foot in a theatre attend this show (like Wicked)? The more answers that can be gauged from questions like these, the more appropriate the movement can be. Finale As long as there is existence, there is evolution. Therefore we must hope to see far more evolved movement come to the stages showing Musical Theatre than the current scope of choreography that is being displayed. Starting this project with it in mind to be a wholly practical piece, I have found that instead twinning the practical element with this dissertation has ultimately assisted and developed my own choreography, within this module and separately from it. I hope that across this Independent Project I have made it very clear that I am not questioning the calibre of the literal steps in Musical Theatre dance. I am questioning the thought behind these said steps; the story being told through them (or lack of…). It is ultimately difficult to grasp a solid reason why, when there are so many capable, innovative creators of 11 movement, there seems to be a divide drawn between those who create dance and those who create dance for Musical Theatre. There are more stories being told completely mute under the dance spectrum than there are being told only partly mute in West End and fringe theatres. The graduates emerging from Musical Theatre studies get more and more talented every year due to the demand there is in the current climate, where we are in excess of talented Musical Theatre performers. There is no reason to believe that the auditionees to be successful in their efforts to land a part in shows could not cope with the skill necessary to execute plot advancing choreography in a thoughtful and illuminating manner, as Keith Garebian notes – after the making of shows like West Side Story, performers “are required to have a higher level of proficiency than ever before”29. Irrevocably, I have to believe that somewhere along the line in the future development of Musical Theatre, choreography will eventually prevail as just as strong a tool for advancing the plot of musicals as the other elements. 29 Garebian, The Making of West Side Story, p23. 12 BIBLIOGRAPHY Ashley, Linda. Essential Guide to Dance. London; Hodder and Stoughton, 2002 Au, Susan. Ballet and Modern Dance. London; Thames & Hudson, 1977. Berkson, Robert. Musical Theatre Choreography. London; A & C Black, 1990. Blom, Lynne Anne., and L. Tarin Chaplin. The Intimate Act of Choreography. London; Dance Books Ltd, 1989. Craine, Debra. Oxford Dictionary of Dance. Oxford; Oxford University Press, 2000. Franklin, Eric. Dance Imagery for Technique and Performance. Champaign; Human Kinetics, 1996. Garebian, Keith. The Making of West Side Story. Oxford; Mosaic Press, 1998. Humphrey, Doris. The Art of Making Dances. London; Dance Books Ltd, 1987. Kislan, Richard. The Musical: A Look at the American Musical Theater. London; Applause Books, 1996. Levy, Fran. Dance and Other Expressive Art Therapies: when words are not enough. London; Routledge, 1995. McLee Grody, Svetlana, and Dorothy Daniels Lister. Conversations with Choreographers. Portsmouth; Heinemann, 1996. Schlundt, Christena. Dance in the musical theatre : Jerome Robbins and his peers, 19341965, a guide. London; Garland, 1989. 13 Agnes de Mille Dances, 2002. Agnes de Mille’s Biography. [online] Available at < http://www.agnesdemilledances.com/biography.html> [Accessed 15th February 2011] canfumaster, 2010. Broadway routine Tommy and Mandy week 4. [video online] Available at < http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jfK6Wm4QoNw > [Accessed 1st April 2011] dancersover40, 2008. The Dancer as ACTOR in Gower Champion Shows -- and a tribute to Marge. [video online] Available at <http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z0UoFogBFIU> [Accessed 1st April 2011] History World: Histories and Timelines, 2001. History of Dance. [online] Available at <http://www.historyworld.net/wrldhis/PlainTextHistories.asp?historyid=ab82> [Accessed 19th March 2011] Musicals 101: The Cyber Encyclopaedia of Music Theatre, TV and Film, 1997. Dance in Stage Musicals, part III. [online] (May 2011) Available at <http://www.musicals101.com/dancestage3.htm> [Accessed 9th February 2011] National Endowment for the Humanities. The Dance Master: The Legacy of Jerome Robbins. [online] (September/October 2004) Available at <http://www.neh.gov/news/humanities/2004-09/robbins.html> [Accessed 15th February 2011] paulaaquino, 2008. The Little Mermaid On Broadway – Under the Sea. [video online] Available at <http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2DUXVAg7oWg> [Accessed 1st April 2011] PJNYC, 2009. Tommy Tune Steps in Time – A Broadway Biography in Song and Dance. [video online] Available at < http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZVE_sVcQaaM> [Accessed 1st April 2011] 14 Sadlers Wells Theatre. About Us. [online] Available at <http://www.sadlerswells.com/page/about-us> [Accessed 5th May 2011] SophiaBPuentes, 2010. 42nd Street (Broadway Revival) – “42nd Street” / “We’re in the Money” (LIVE – Tony Awards). [video online] Available at <http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i5rCPKY-9zs> [Accessed 20th February 2011] ________., 2010. Crazy For You (Broadway) – “I Cant Be Bothered Now” [LIVE – Tony Awards]. [video online] Available at <http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YDJ6XFgze5M> [Accessed 1st April 2011] Stagedoor2590, 2010. The Juggernaut – The Wild Party (Off Boradway) [source misspelt]. [video online] Available at <http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YERYu7toqMk&feature=fvst> [Accessed 20th Febraury 2011] The Free Dictionary. Definition of musical theater by the free online dictionary. [online] Available at <http://www.thefreedictionary.com/musical+theater> [Accessed 15th February 2011] 15